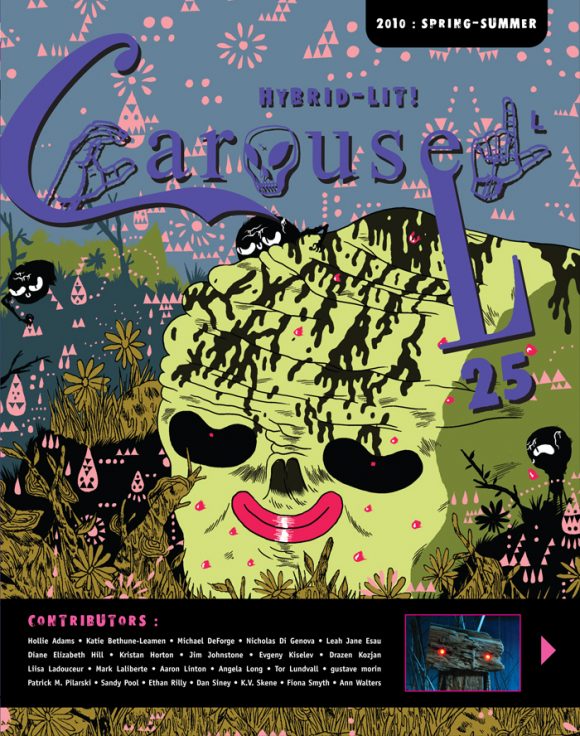

From the Archive: Tor Lundvall ‘Transforming a Landscape’ Interview (CAROUSEL 25)

New York-based downtempo producer Tor Lundvall balances his music production with a parallel career as a painter of cloudy autumn days & ghostly landscapes

Interview conducted May, 2009

Sound is primarily for the ears; painting is primarily for the eyes. In your creative life, how are the two mediums interconnected and where do they overlap?

For me, the line is most definitely blurred as to where the two pursuits overlap and blend; there’s such a strong bond between the painting and the music that it’s difficult thinking of one without the other. When I record, I’m constantly seeing images, and when I paint, I’m constantly hearing music — either inside my head or out from the stereo.

Your paintings centre around three basic elements: the landscape, memory and imagination. What is it about nature and fantasy that you find so compelling?

The endless supply of mystery and freedom they offer: nature and fantasy have no limits.

You have often said that the figures that populate your artworks are merely passing through the mystery and silence of the landscape — a fitting description. Can you tell us a bit about the use of characters in your work, and how you ‘dress them’ using that basic idea?

As a painting develops, figures are gradually pulled out of the landscape. Although they’re “merely passing through” as you’ve quoted, there is also a strong bond between the figures and their surroundings. There is a sense of playfulness to some figures and a sense of menace to others. It’s difficult analyzing individual characters and what they ultimately represent; they just make sense to me on an instinctive level.

There is something carnivalesque and decisively pagan about the costumed strangers populating your landscapes. Is the idea of ritual an important one in your own life?

On a subconscious level, yes. Ritual isn’t something I actively think about. It manifests itself at the right times and always when I’m alone in nature.

Regarding influences, you’ve mentioned Scandinavian painter Edvard Munch, as well as American painter Albert Pinkham Ryder. Are there any contemporary painters (or visual artists) that you find inspiring?

I’ve been a fan of Robin Storey’s art, both musically and visually over the years. I’m more inspired by contemporary musicians than I am by contemporary visual artists. However, this is probably due to the fact that I’m simply not aware of their works. I’m a bit old school when it comes to painting, and prefer wandering around museums instead of art galleries.

Many of the photos I have seen of you at work focus on capturing you out in nature with easel and brush. Do you prefer to paint outside? Are there challenges?

I paint mostly indoors; however, there’s nothing quite like the experience of painting in the field. It’s more challenging on a variety of levels, primarily due to the way the light changes during the course of an afternoon. The landscape transforms drastically with the shifting light and you must constantly keep up with it. Painting directly from nature also frees up the mind. I usually end up capturing shapes and colours that are far stranger and more complex than anything I would have come up with in the studio.

You have described approaching composition in a visual way, starting with a very basic idea and slowly building on it. Can you talk about your process?

I usually start off with a basic loop or a series of sounds that appeal to me and slowly build on that foundation; the process is similar to painting, where I start by applying thin washes of oil paint and gradually build up the surface until there is a sense of resolution.

Your compositions are strongly impressionistic. The work is steeped in the ambient tradition, yet retains a strong sense of melody that is often missing from this kind of music production. How does melody embed itself into the works?

I suppose the presence of melody comes from years of reluctantly studying classical piano, and later, with more interest, jazz piano. I also grew up listening to synth-pop and even recorded several pop-oriented tracks early on, some of which appeared on my first album, Passing Through Alone. Things started getting interesting around 1995 when I started recording my second album, Ice; the melodic elements evident in my early pop tracks started merging with my ambient side resulting in unique atmospheres and compositions.

As an ambient producer, you largely resist the ‘slow build/slow drift’ method of composing that largely defines the genre; with a few exceptions, your tracks rarely exceed five minutes in length. Can you talk about this key difference in your work?

My early ambient recordings were somewhat longer and more drone-oriented; however, things changed later on. I just prefer shorter pieces, I suppose. Although I love listening to extended ambient compositions, especially when I paint, I also adore albums where each track is like a little gem within a larger, unfolding sonic story. Brian Eno’s Music For Films and Harold Budd’s The Serpent (In Quicksilver) are two favourite examples of this.

How do you know when a composition is completed?

I just feel it. I’m usually not satisfied until the music engages me completely and all the details are in the right place.

I love the following quote relating the joys of studio production: “Happy accidents, overlapping layers of sound, and the endless mystery of reverb and echo.” What is it about reverb that is so magical to the ear, so cinematic?

I think it’s the unexpected patterns reverb creates within the music and how it blurs, alters and distorts sound in infinite ways. It’s like rain transforming a landscape. There are some who perceive reverb as a gimmick or trick to mask the inadequacy of the music; it can certainly do this, but it can also enhance the music in endlessly fascinating ways.

As your label has done the job of marketing your work, the term ‘File under: Ghost Ambient’ has become somewhat of a catch phrase that reviewers often build upon. How do you feel about the term?

I’ve never been fond of labels, to be honest. An art gallery, for instance, once labeled my paintings ‘Post-Modern Gothic’ much to my annoyance. I coined the term ‘Ghost Ambient’ to avoid being pigeonholed by others at their whim. Although the term makes sense for a variety of reasons, I’d rather not be “filed under” any specific genre, as my (former) label attempted to do. In the end, labeling is usually favoured by business minded people for short-sighted marketing ploys. It serves little purpose for me, but I understand from a marketing standpoint the desire to do so.

Is it becoming an actual subgenre? Are there other sound artists that you feel inhabit the same sonic territory?

I don’t know if it’s come to that yet. As one reviewer aptly pointed out, adding yet another subgenre only manages to further confuse an already confused record buying public. There are certainly other musicians I feel a kinship with sonically and otherwise, William Basinski and Mark Nelson of Pan•American, to name two of my favourite music makers.

As an artist following two distinct paths, you’ve had to deal with both record labels and art dealers on a professional level. How have these necessary relationships affected your ability to make a living as an artist?

All in all my business experiences have been disappointing; however, if I hadn’t exhibited my paintings, then I probably wouldn’t have had the exposure I needed to successfully sell my work privately. The same goes for my music. Maintaining business relationships has never been easy, however. Things usually start off well and then deteriorate over time. Promises are made which are never carried out, followed by excuses attempting to justify why this or that transpired. Luckily, there have been a few rare exceptions.

Which world is ultimately harder to navigate commercially?

I suppose the art world is more difficult. With music, you can print up an edition of CDs or LPs and mass distribute it. In the art world, unless you’re editioning prints, you’re selling original paintings that most people can’t afford and will likely never get to see in person. Art openings can also be a trying experience for those with a reserved nature!

I’d like to ask you about torrent culture as it relates to the distribution of sound works. Have you seen any kind of effect, positive or negative, since file sharing has become a virtual standard?

I’ve certainly noticed an effect, although it’s not a positive one from my perspective. There’s little connection between audience and artist through file sharing and it’s plainly detrimental to the artist’s ability to recoup expenses incurred to release and manufacture their albums. In fact I recently discovered a blog offering one of my albums as a free download without my consent; fortunately, they respected my wishes and removed the link. Unfortunately, it seems there’s little that can be done about it otherwise.

Search engines provide doorways to possible worlds, in theory making the smallest of creative movements less difficult for the curious to access. Does the average person notice all these small doors? How does this affect the idea of subculture?

I don’t think the average person ever noticed much of anything throughout history; if they did, the world would be in better shape today. Subculture will always exist and manifest itself in new forms in spite of the changing times. There will always be a handful of individuals creating lasting, meaningful art that will shine through the sea of garbage. Somehow, it always does.

What’s the plan for your next new recording?

Right now I’m working on an instrumental album called The Shipyard, based on one of my earliest ambient recordings. Progress is slow, but it’s coming along nicely.

Transforming a Landscape

appeared in CAROUSEL 25 (2010) — buy it here