From the Archive: Winnie Truong (CAROUSEL 28)

WINNIE TRUONG

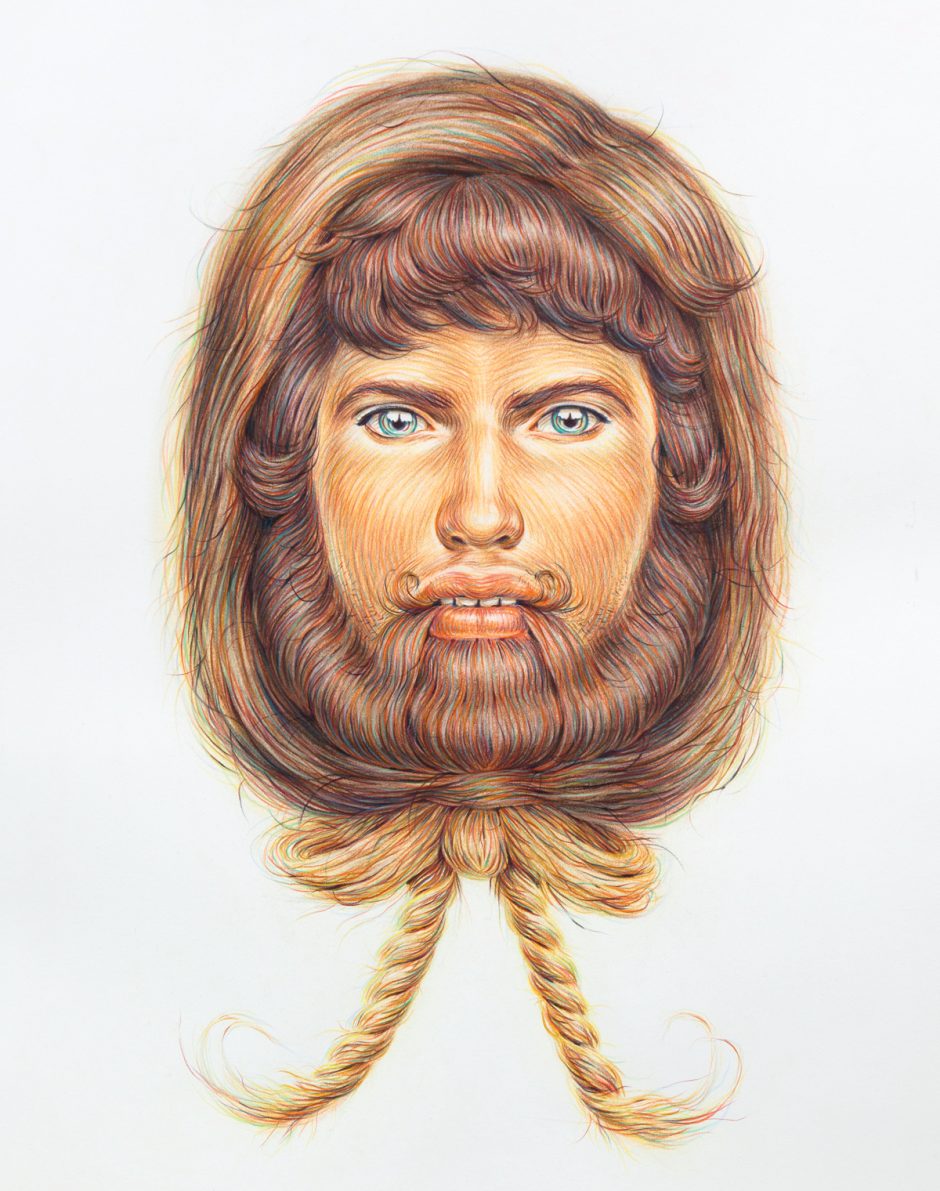

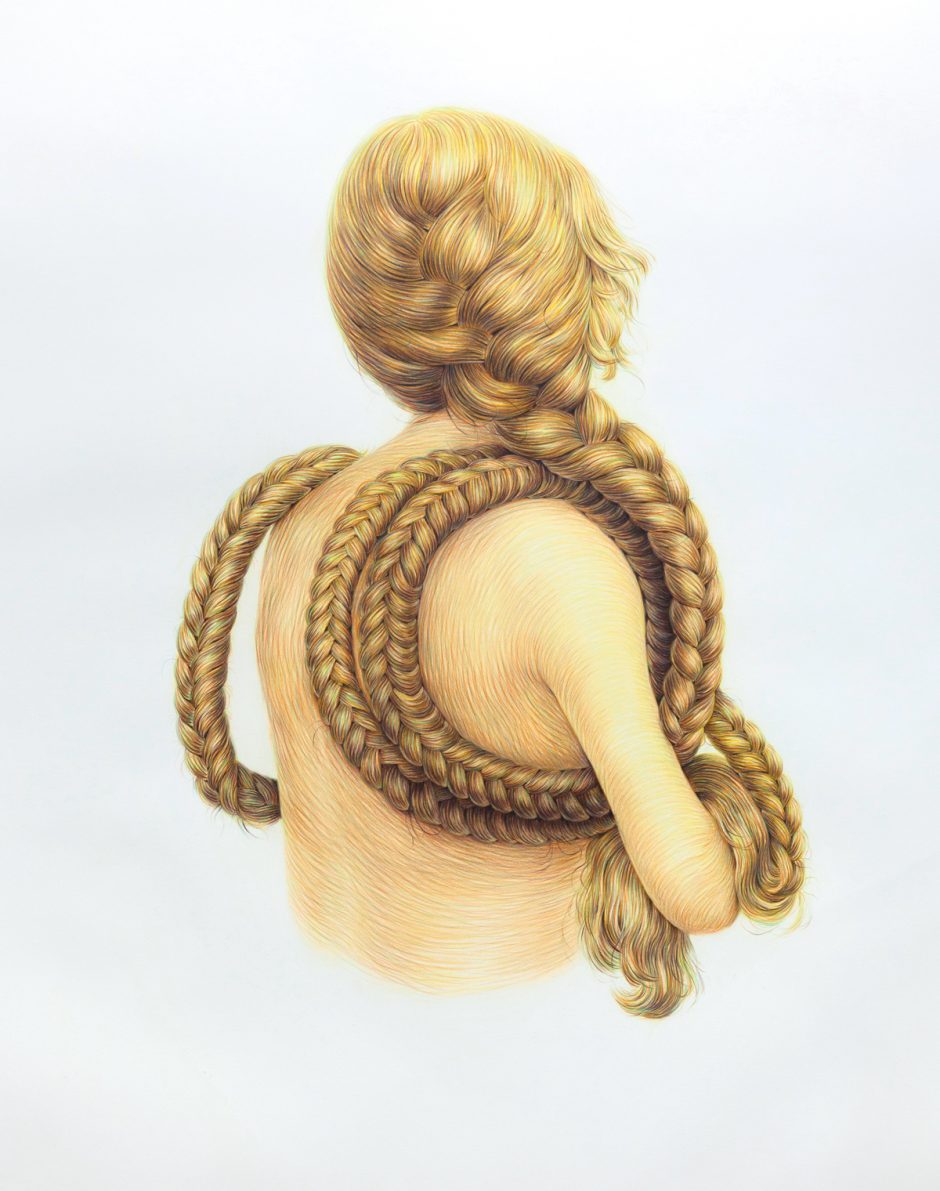

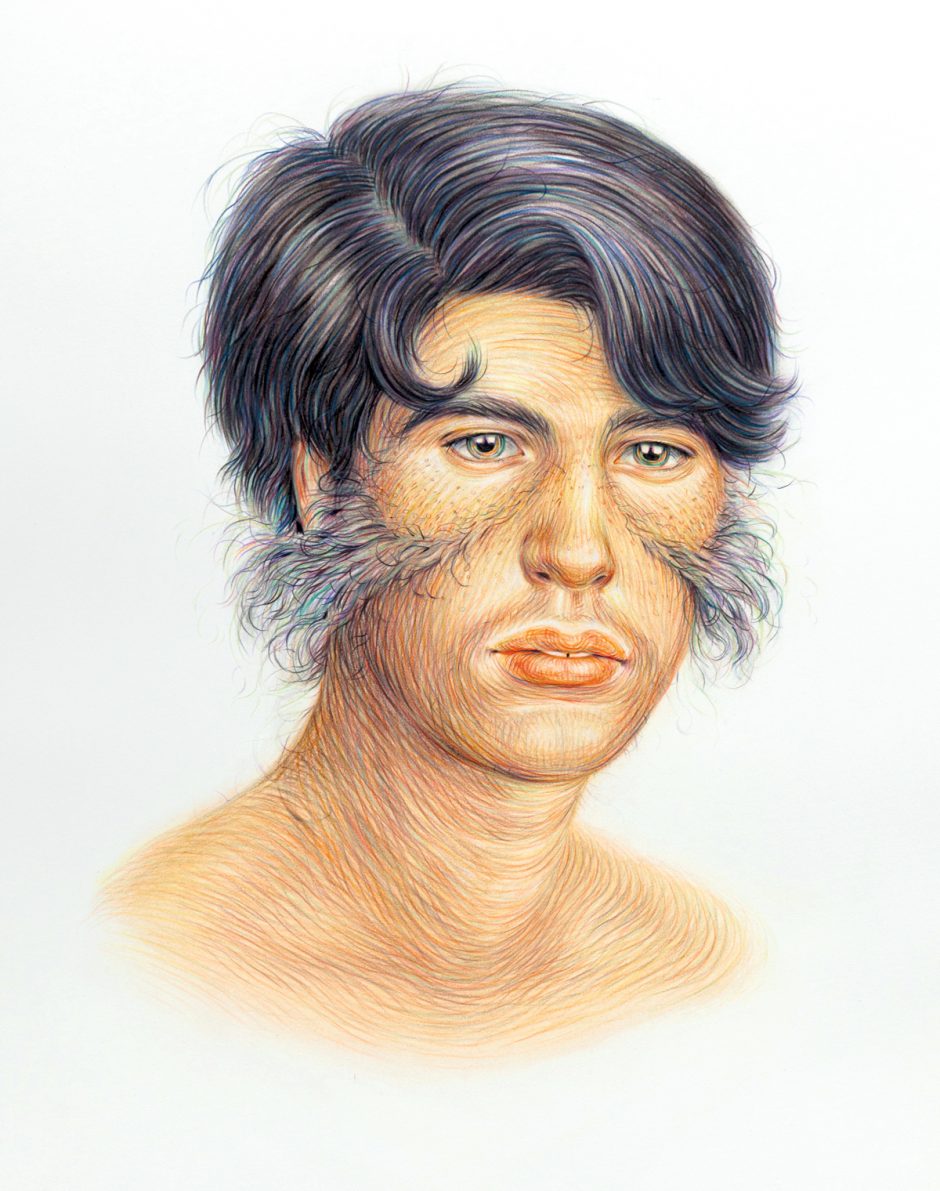

Portfolio: Trichophilia

They stamp on any change: they close the way and keep the type fixed because they’ve got the arrogance to think themselves perfect. As they reckon it, they, and only they, are in the true image; very well, then it follows that if the image is true, they themselves must be God: and, being God, they reckon themselves entitled to decree, “thus far, and no farther.” That is their great sin: they try to strangle the life out of Life.

— John Wyndham, The Chrysalids

— pencil crayon on paper, 30in x 22in

With The Fringes, her latest solo show, Toronto artist Winnie Truong presented a series of large, pencil crayon portraits of tender young outcasts whose body hairs have taken on lives all their own. The Fringes is a clever little title, referencing both the ornamental fringe trim in hairstyling and fashion — a shaped cutting of the front part of the hair that is combed forward and hangs or curls over the forehead — and more esoterically, the enigmatic forbidden territory in John Wyndham’s 1955 sci-fi novel The Chrysalids — an untamed radioactive zone occupied by outcasts at the edge of society, those individuals not conforming to a strict physical norm whose slight differences were considered “blasphemies.”

Contrasting beauty and bodily mutation, there is an element of freak show culture embedded into Truong’s cast of characters. At first glance, they all seem like variations on the beastly human marvels that delighted audiences of yesteryear in carnivals touring across the land — those poor outsider souls burdened with hypertrichosis, an abnormal amount of hair growth on the body. Truong, however, likes to downplay the sideshow elements in the work, pointing to her key inspiration in the kind of mutant oddities represented in science fiction tales.

Early on in her artistic practice, Truong focused on teaching herself classical painting techniques, fueled by her love of art history and a personal exploration into cultural identity. However, in the past few years her art practice has evolved away from painting, and today it consists primarily of drawing; similarly, her interests have moved away from directly examining her own culture and towards an exploration of the idea of the mutant as an outsider.

— pencil crayon on paper, 72in x 48in

Why focus on hair as a marker of difference? Hair is a biological material that grows continually throughout our lives, one that must be properly managed through acts of cleaning, accessorizing, shaping or removal. Hair can spark an erotic desire in some, or trigger a feeling of revulsion in others, depending on the person and their particular predispositions. Most notably, hair, as an extension of the body, gets dirty, and it can go wild if it’s not carefully maintained. And anything that potentially untamed is sure to be uncomfortably strange in the right — or more specifically, the wrong — context.

At once anthropomorphic, expressive, and self- ornamenting, hair becomes a significant extension of character in Truong’s practice. Manes are overgrown in unexpected places, causing its wiry, coarse unkemptness to elicit a sense of difference or otherness. In different instances, when the hair waves, curls and cascades, not unlike a powdered wig, it evokes expressions of elegance and majesty. Truong exploits the non-verbal communicative power of hair, socio-historically loaded as it is with notions of identity, gender and social status.

With an intelligent and arresting brand of visual wit, Truong also explores her tricophilic passions as a way to engage in a physical relationship with the act of drawing. Producing large-scale, labour-intensive drawings using only pencil crayon on paper, her portraits exploit the drawn line to manipulate hair and flesh. Working strand by strand to build up each image, Truong’s process involves intuitively allowing the details of her hairy personas to evolve over time. The incremental layering of line after confident line produces a cumulative effect that defines the dimensionality of the drawing; each portrait is comprised of a mass of perfectly described, directional coloured lines. There is an undeniable technical beauty to the control Truong exhibits in her mark making, one that aligns itself to hyperrealist gestures.

The project she is engaged in gets stronger as it accumulates, with each new portrait adding to a complex dialogue on the beautiful and the beastly. Although some might find the fantasy figures disagreeable, it’s easier to view them more as exotic at their core. The ornamented faces that “dare to exist at the fringe of beauty, fashion and biological possibility” have a connection to the world of fashion that is undeniable. This may be because each new character is created using figurative references taken from the pages of glossy magazines. Reinventing the figure from a position of ambivalence and imagination, Truong “adapts the sharp contrasts and vivid colouring of the printed source,” and applies a surreal touch to them, making visual statements through ornamental transformations of hair and flesh. By stripping her characters from their logical, fashionable environments and allowing them to float in white space, Truong is better able to focus our eyes directly on the twisted and braided ornamentation occurring in the work.

— pencil crayon on paper, 20in x 22in

Aligned with the age bias of her source material, Truong’s studied characters tend to be youthful markers of difference, authoritatively posing for the viewer as any true model specimen would do. And youth is almost never repellent; it will more often be viewed as beautiful and healthy in its disposition. In this sense, her characters are minor mutants rather than full-on freaks, youthful personalities who tend to startle and arouse curiosity in the viewer, but don’t really elicit any kind of true feeling of repulsion. Therefore, the works don’t always hit their mark when they are positioned as a way to challenge our “heavily coded ideas about the beautiful and the grotesque that exist in our culture”; instead, they often enforce the idea that difference is an exotic attractor, a way to drive change and expand the realms of fantasy within the popular culture.

For Truong, this is probably a fair and acceptable reading. She approaches her work in a way that is meant to be ambiguous, and is vocal about wanting her work to remain apolitical, to “have its worth reside in the emotional disquiet of the viewer”. As an image maker, she strives to keep her portraits open enough that they can be examined from a variety of different lenses, offering her audience the room needed to make their own critical associations. This braided approach to working with strands of narrative and popular reference adds strength, body, shine to her ideas — each image builds on the last, in both form and substance.

Rinse thoroughly, repeat.

Special thanks to Erin Stump Projects, Toronto.

Portfolio: Trichophilia

(with additional sidebars)

appeared in CAROUSEL 28 (2012) — buy it here