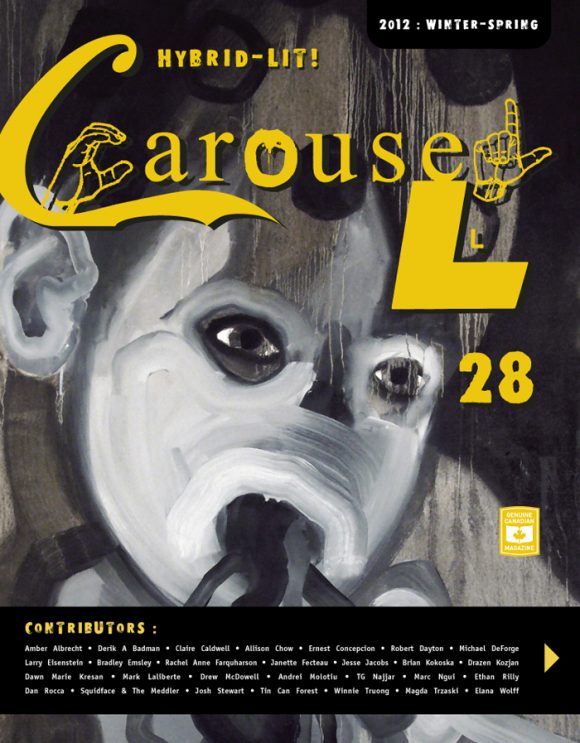

From the Archive: Brian Kokoska Interview (CAROUSEL 28)

Among the roster of emerging artists today, scenes of indulgently deviant behaviour bare new skin under the paintbrush of Canadian Brian Kokoska.

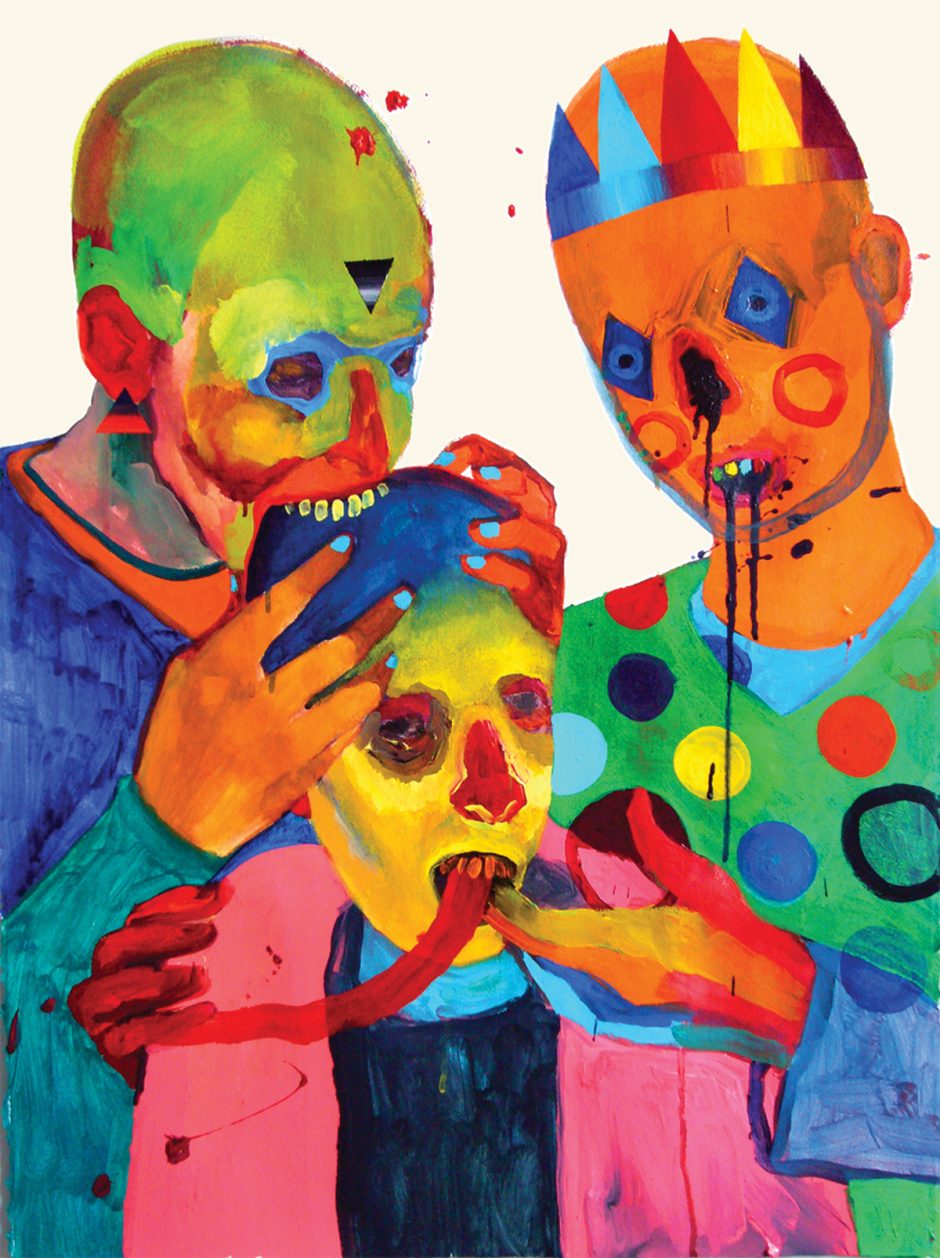

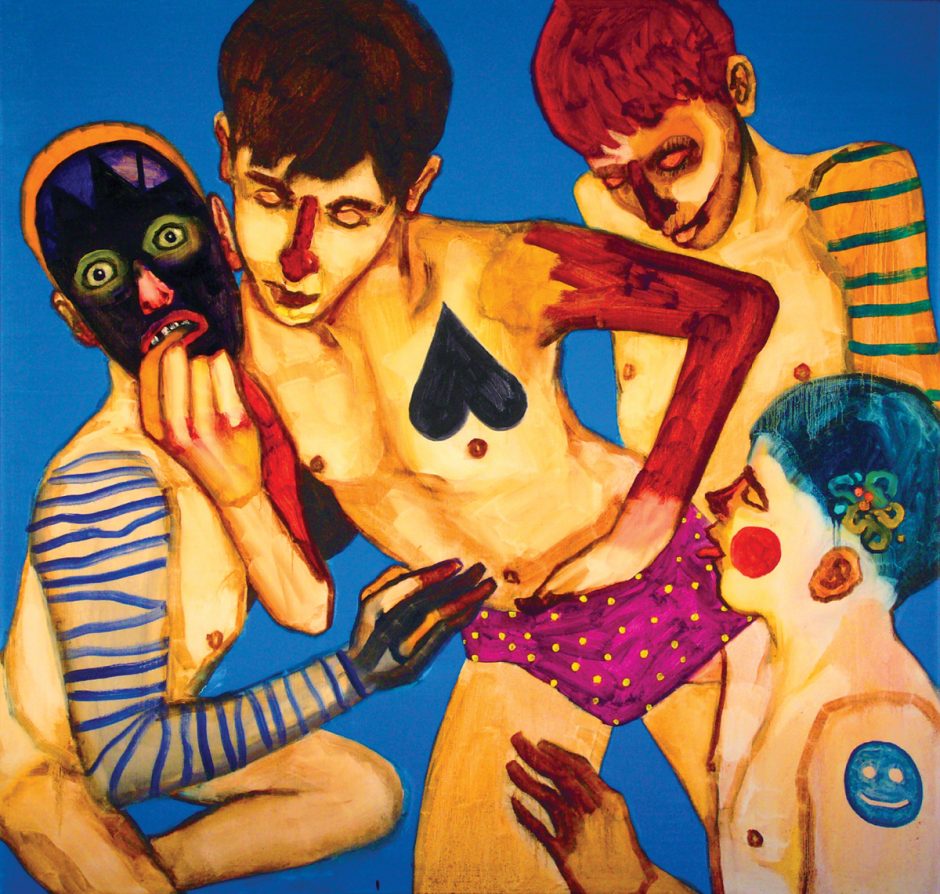

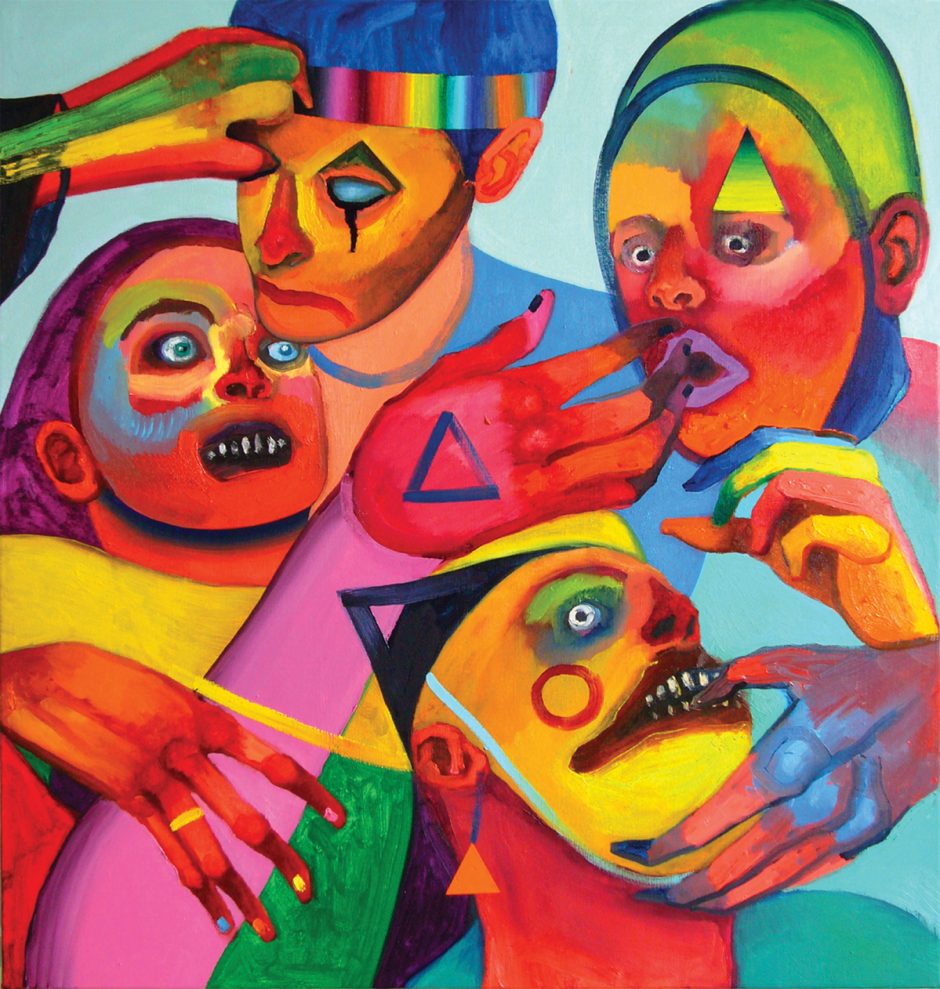

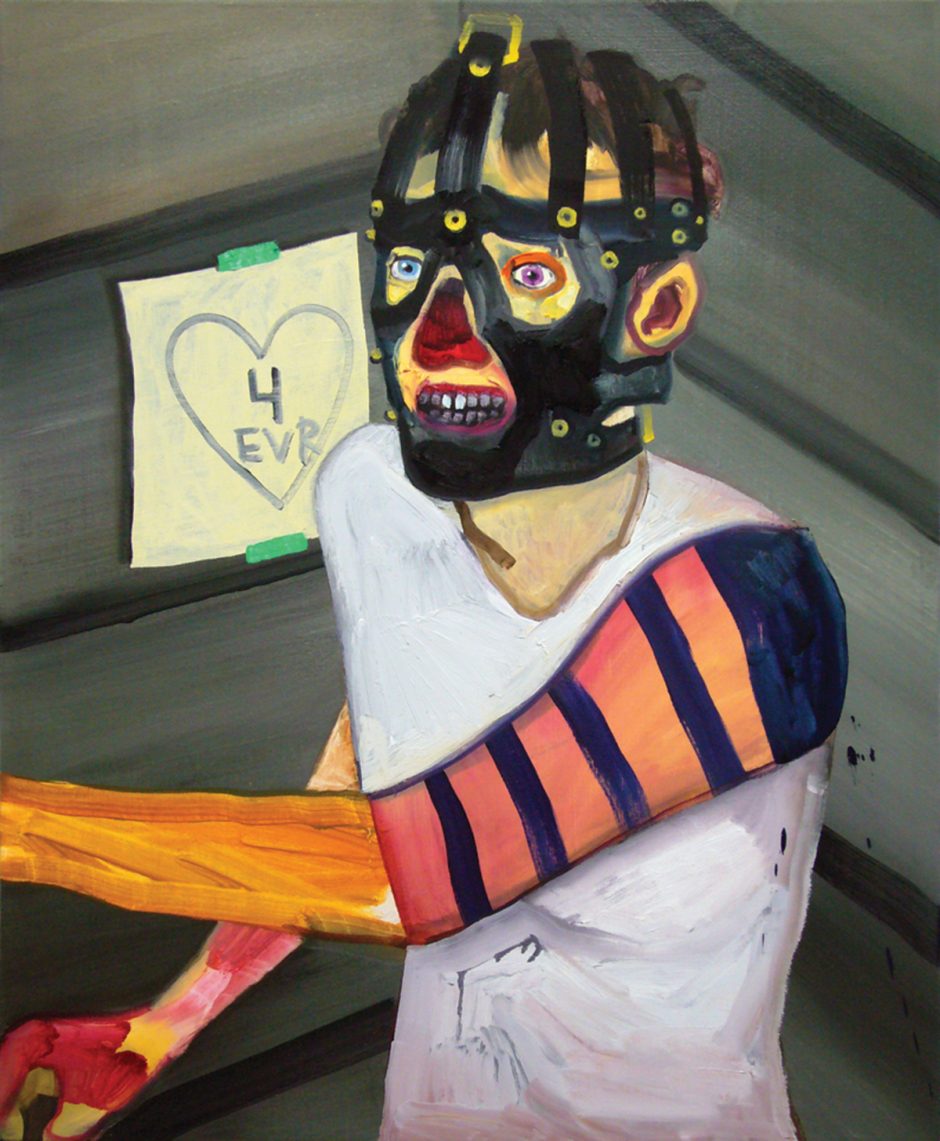

A recent New York transplant, Kokoska creates large scale canvas-based works using a chromatic and figural vocabulary complimentary to the themes of the carnivalesque and the grotesque. Within the art historical canon, these topics have been referenced in a moralistic way — particularly by Netherlandish painters such as Hieronymous Bosch and Pieter Brueghel the Younger. An examination of recent artistic production reveals the formation of a foundation for contemporary pop culture based on the very same themes, though moralistic maxims have been replaced by an enunciation of debauchery evident in the practices of a long list of artists, from comix champion R. Crumb to Postmodern heavyweights like Mike Kelley and Sigmar Polke.

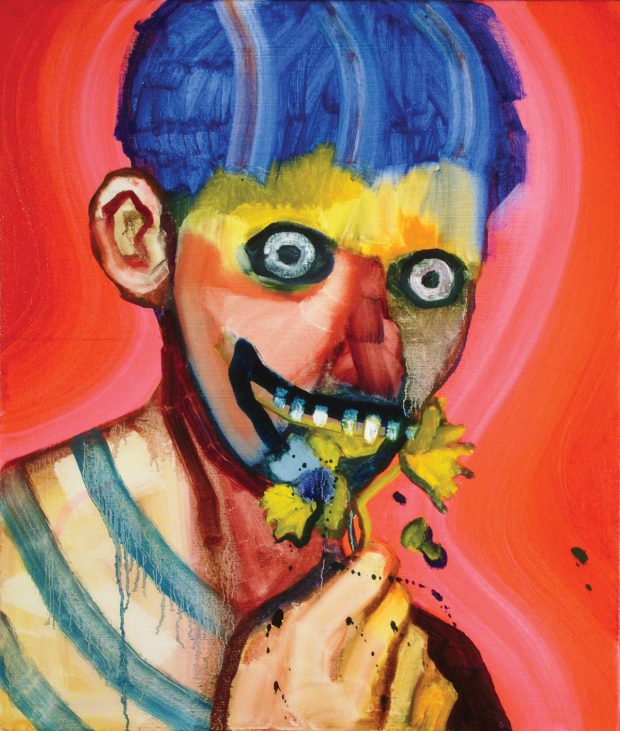

Liberties of a burlesqued nature are taken no less by Brian Kokoska. Indeed, he proffers them readily. Highly saturated colours, phallic shapes and clusters of nubile bodies clambering over each other are all aspects of this young artist’s visual arsenal. Yes, arsenal. Kokoska’s province is his ability to assault the viewer’s senses with a brash palette and even brasher subjects in a way that hurts so good.

Interview conducted June, 2011

Having completed your undergraduate degree in Vancouver, BC, you recently switched coasts to move to New York. Do you think that living in Brooklyn affects you personally and artistically? I would imagine that the street life here is a prominent aspect of your daily existence.

Where you live and where your studio is located certainly affects the work you produce. For me, it always takes a while to figure out exactly how my work is being affected by my current environment. My work is shaped by my daily surroundings just as much as I am influenced by other art work. I am constantly being exposed to music, I go to a lot of lively parties and events, and am frequently bombarded by banner after banner after banner in New York. We are a society that is over-stimulated and over-exposed. There is a grunginess to the material I encounter here that I really enjoy. When you live somewhere more remote, where the tone of the neighbourhood isn’t necessarily happy due to economic status, etc. it must have some sort of presence in your art. I love where I live in Brooklyn and there is definitely something that carries on from the street life and club scene in this neighbourhood in my work. I am very happy to have moved from Vancouver into a new urban environment. It is very inspirational. People here are very real compared to Vancouver, where the demeanour is more relaxed but also consciously composed.

People are rather happy and easy-going in BC, which makes life less stressful. In New York, people are very genuine and speak their mind, which I have come to appreciate.

I find there is a directness in a city like New York that can be startling — the manner with which people conduct themselves seems hinged upon an awareness of time and an economy of language. Do you find people here brash?

I do think it is kind of harsh here and people are quicker to judge you without necessarily knowing much about you. I feel like I don’t fit into this neighbourhood, but I like that at the moment. I don’t spend too much time out and about here, but rather go to a few more fun areas to socialize. That said, I like the separation from where I live and work and from where I play. I’m trying to fit in and am slowly finding myself in the process.

Has this process hindered or fostered your search for gallery representation?

I am not represented by a gallery right now. I have a few projects going on but nothing within a particular institution. Despite my earlier comments, I feel really thankful to be in New York. People have been very receptive to my art and have accepted me as a person. Compared to Vancouver, there has been a significantly higher amount of support on the art side for me. I think my comments about judgment were more about the people you encounter daily, on the street, in the subway, in a restaurant.

The art market in New York is so broad that it feels as though anyone can get by making work because most things are acceptable and interesting to someone, which is nice.

Great. Now let’s take an in-depth look at elements of your work that people here have found interesting. When observing jaundice and disfigurement in your paintings, I would suggest that the challenge is to locate the similarity between your own body and the representation’s. By fabricating a barrier between the viewer and the subject, you successfully expose the fear humans harbour of unnatural and transmogrified bodies. Does your subversive imagery stem from your own feeling of otherness within daily life?

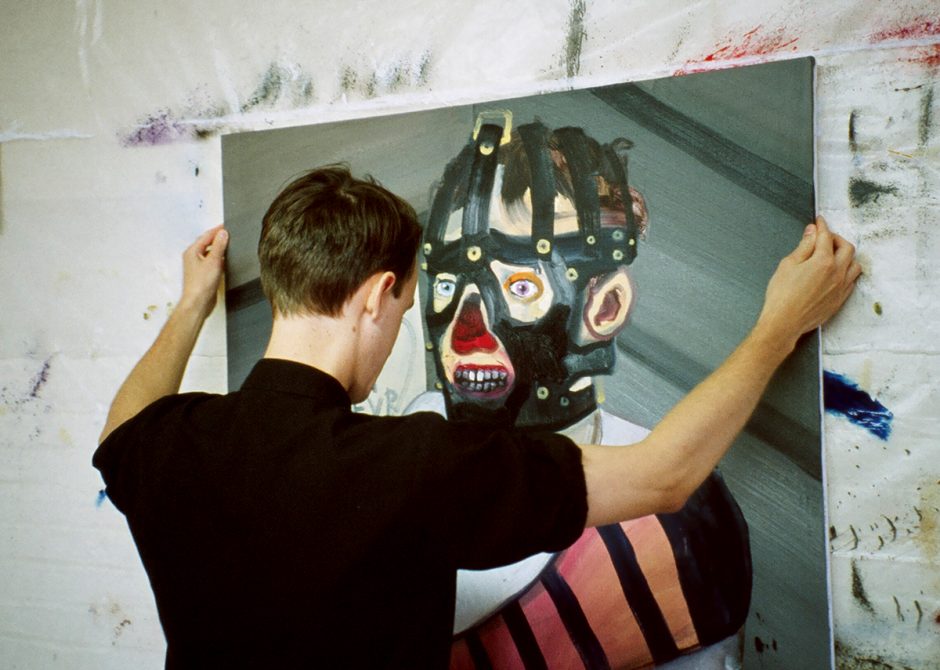

Painting for me is a means to create figures that do not and cannot exist in real life. I try to induce something mysterious in these figures. I want to create imagery that you can to a certain extent relate to — inviting and at the same time sinister. I also like the gender confusion suggested by a lot of the paintings. Some are more sexual and explicit while others simply obscure the body. The gender confusion co-mingles with other subtle references such that anyone can find a personal entrance point into the paintings. It could be simply a complex pattern that apes the textile tradition or something entirely different.

Women rarely make an appearance in your work. Do you find the feminine form is conducive to the unreal figures you are trying to make? Double Veronica (2011) is alarming in terms of the way her face becomes more and more dog-like the longer you observe it.

Actually, I think that much of the time viewers see the female form in my figurative paintings where I wasn’t necessarily making the gender so direct and obvious. I like that kind of mix-up. There are more obvious works in which the inclusion of penises or other body parts means that they are never in question, but I guess I feel a little bit more hesitant and uncomfortable including women in my work because I don’t have a “feminine voice”. I don’t want my practice to be about painting women, partially because I just don’t think that would be the right thing for me to do. I am finding myself less and less close-minded and deterministic about gender, which I like. Sometimes a figure will start off as a boy and turn into a girl by the stage of completion. Sometimes it is just the opposite. I always intend for the work to be playful and I also endeavour to incite in viewers different ways to look at the body.

A lot of my early paintings were based on collages that I would craft out of a variety of pornographic images in order to make an ambiguous and abstracted figure. They were digital collages and so taking them as a starting point is most likely more influential in my choice of boys as subjects.

Clearly delineated sexual difference and formulaically gendered bodies are both very much eschewed by queer theory, creating a theoretical space for the transmutable body. A number of your paintings seem to picture bodies folding into each other to make a kind of poly-humanistic chimera — I am thinking of Black Waterbed (2011), Siamese Twins (2011) and Teething (2009) in particular, but even the compositions that feature larger, orgiastic groups have this tendency. Is the rejection of the clearly identified self, sexually or otherwise, a strong current in your creative process or in the way you perceive human behaviour? Is there psychological disfiguration involved as you imagine your subject matter?

I don’t really think of my work as psychological, although I have heard that critique before. A lot of my impetus is compositional in that I enjoy the progression of multiple figures falling apart until they reach near or complete abstraction. I became bored after rehearsing the same group compositions over and over, so I let them begin to fall apart and found that pattern assumed a large role in the newer pieces. I want the images I create to be stimulating to the eye and thought-provoking in terms of content. The paint application and the patterning is very important.

There is a very pronounced divide between the colour palette you employ — exuberant, juicy — and the content you return to time and again. The co-existence of a perverse, threatening atmosphere and colouristic joviality in your work is startling. Can you talk about the duality of your images? How much does fetishistic behaviour factor into your posturing of the subjects in your paintings?

I am really interested in fetishism and fetishes. I have become obsessed with one fetish at a time and this manifests itself in my paintings. There was a time at which I was obsessed with jewellery and accessories, for example, which was immediately present in my work as different ways of decorating the body. A lot of my interests and the decorations I give my figures have to do with the ritualistic. I have an interest in magic and witchcraft — things I don’t know from first-hand experience but that I want to explore in a way that is fun. These things aren’t real to me, but they become so in my pictures. It is an interesting endeavour to play around with fetishes that you don’t have personal experience with or even those that you do.

Teeth are often visibly highlighted in your compositions — is this one of the first ways you would choose to transform a subject’s face from familiar to feral?

A lot of my paintings started off with prominent oral elements. People often speak first about the presence of mouths and actions like sucking in my work. I wasn’t aware of this thread through my work until people started pointing it out. I will admit that I like the idea of orifices and crevices, playing with holes and stuff like that. It is not premeditated, however. There isn’t a direct connection between what manifests itself on my canvases and my intentions when making a painting.

Wouldn’t you say that highlighting one feature on a face — teeth or a nose, for example — makes the face more immediate and active? It forces the viewer to really notice what he/she is looking at.

Oh definitely. I am always looking for different ways to play with traditional representational forms. Some of my subjects have a face but others have a lack of a face or a mask-like, unknowable quality to their face. I am always trying to find new ways to make a face because to me, the face is the most important part of the body in any composition.

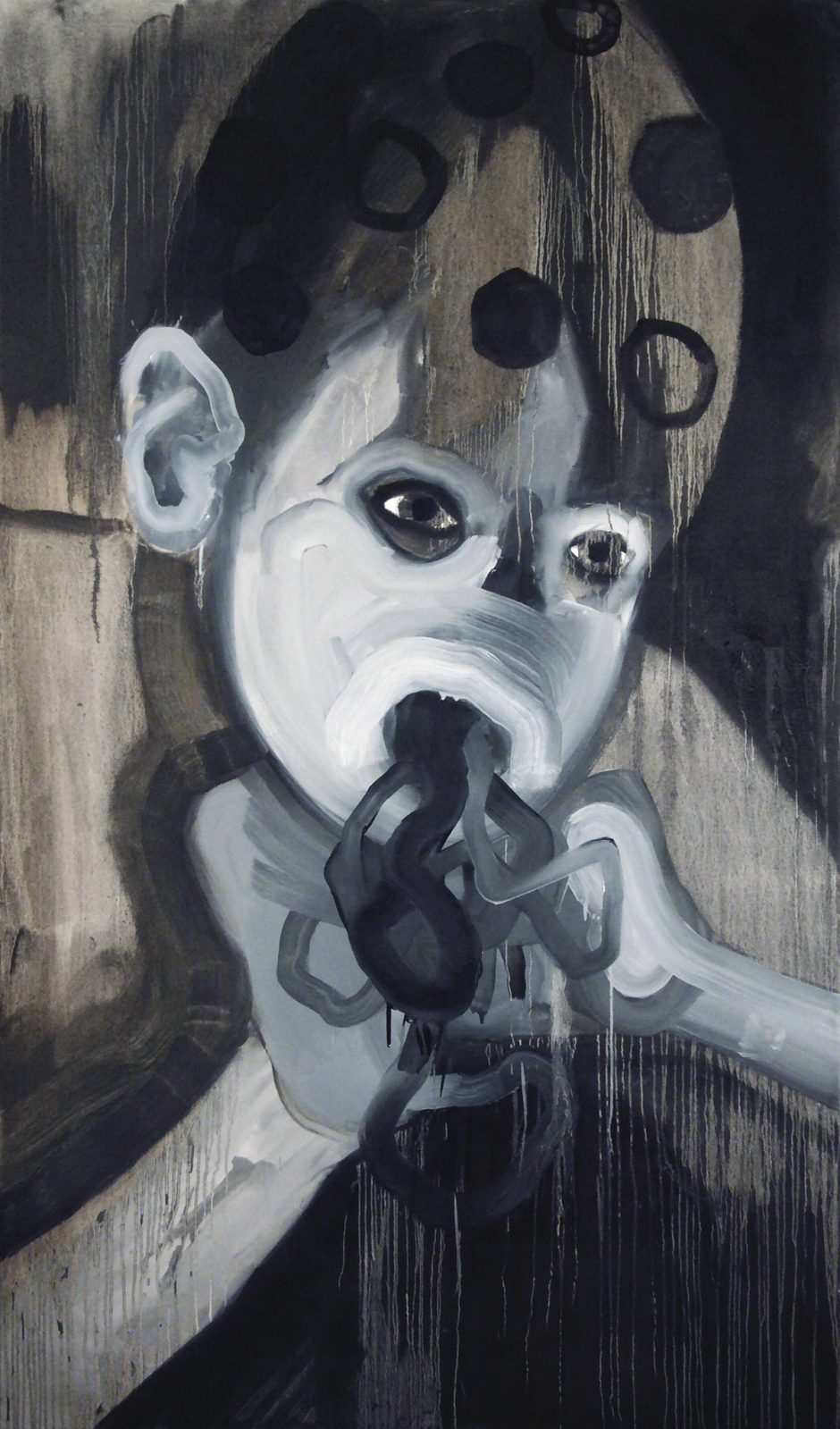

Your latest works incorporate a darker, more morose colour palette. The yellows have turned to ochre and the figures have begun to take on an Egon Schiele-like aesthetic — especially paintings such as Gimphead (2011). The darkened nose and angular body is one of Schiele’s calling cards, to be sure. Moreover, Schiele’s oeuvre consists of exposing the carnal proclivities of humankind in a way that resonates with your work. Are you aware of these similarities and the direction your work is taking?

Egon Schiele is an artist I discovered as a child, so I was probably influenced by his work at the most unconscious level. In general, however, I don’t tend to look at a lot of historical work. Or perhaps it is that I do look at traditional work but not with the intention to make any kind of allusion to them. I look at a lot more new work — not only painting, but video and new media. All kinds of media. I have heard the comparison between my work and Schiele’s before, but I really try to continue to look for new ways to express the idea of the figure.

I don’t think that painting in this way necessarily means you want to be a part of a subversive or marginalized section of society — instead, it is a way to extend yourself into different modes of being without actually performing these roles in real life. This is what a fantasy is based on; whether materially, physically or psychologically, you are locating yourself in an environment that you might otherwise never find yourself in but you are curious about.

Definitely. My paintings have a lot to do with fantasy. Some are over-the-top and some rely more on events or situations that I have encountered in life but where there isn’t a one-to-one relationship. There is something of a remove between my depiction of the situation and what is feasible in life, partially because memory makes things convoluted. That lends nicely to fantasy, however.

Early Twentieth Century Modernism placed an over-arching emphasis on the formal properties of each medium, undermining representational subjecthood and resulting in abstracted work. Given the prominence of the figure in your practice, how much was Modernist theory a part of your formal education?

When I was in school at Emily Carr, Vancouver’s painting scene was very much steeped in new abstraction and what I felt was awkward geometric abstraction. My professors were very concerned with non-representational modes of painting as a means to fully present the formal qualities of the medium. During my critiques, I got more feedback about my paint application than anything. My professors seemed to actively avoid analysing or commenting on the other elements of my work. I had a great experience while in school but the formal platform of the work I was surrounded by did make me feel as though the west coast of Canada wasn’t the best place for me.

Recently, however, I have noticed a definitive move towards abstraction. Now that you are not located in BC, do you find yourself coming back to the painting methodologies that originally pushed you out of the environment?

I think I always played around with abstraction but I was primarily showing figurative work. I didn’t keep a lot of my less figurative pieces and conducted those experiments outside of my exhibition practice. Now

I am feeling more confident that images can be more abstracted but retain the urgency that I find appealing. Being able to use abstraction to express something like sexuality is fun, but I think I will always go back and forth between abstraction and figuration. I would never call myself an abstract painter.

There is a clear tension between the figural and the abstract in pieces like Tongue Tangle (2011). What does straddling the gap between the two camps achieve for you artistically?

There are definitely some formal reasons for painting in both modes. I like the idea of picture-making wherein each piece of work has its own personality within the greater constellation. I like how an overtly figurative painting works with an abstract work next to it. Also, a lot of the digital work I was creating before was made from digital photographs of my paintings. I would cut them up and collage them together to create digitally abstracted assemblages. The more I made these digital manifestations of abstraction and crumbling composition, the more I wanted to recreate similar properties on canvas.

I like the tension between the form and the field in Tongue Tangle. Most images start off very precisely delineated in my mind — almost as clear as a photograph. So when the figure starts to disintegrate but maintains certain areas where it is representational, it is almost more fun.

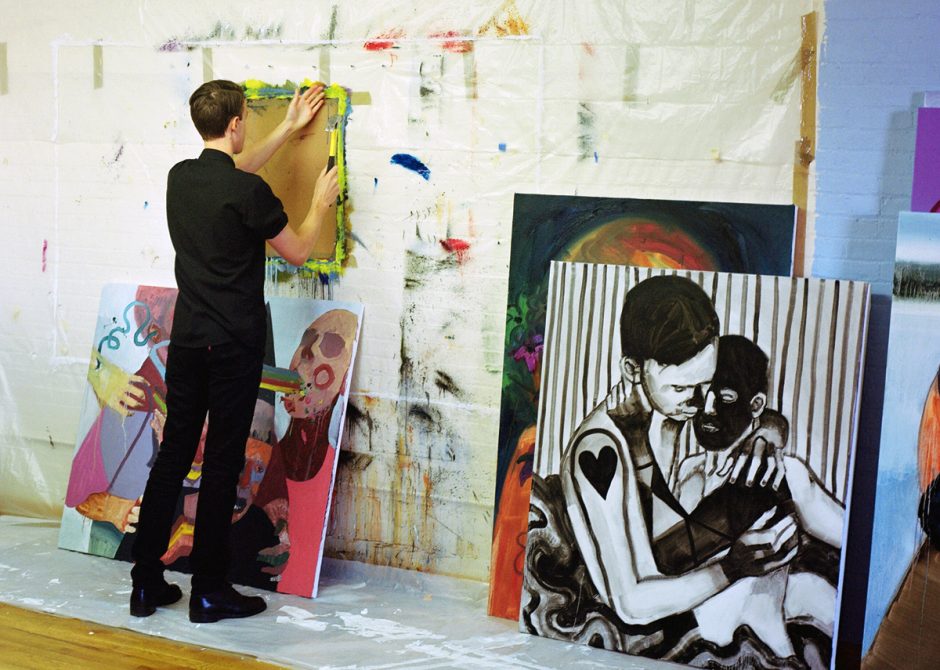

How long does it typically take you to make a large canvas work? You seem to be experimenting with a loose and fast mode of creation recently.

I think that the paintings I was making in 2009 and 2010 display a kind of obsession with precision and layering; I was spending weeks on each large painting and there was a very specific process to their execution. Now, my work is approaching a place where it is more immediate and less precious. I feel as though I am able to experiment more, which enables me to make new kinds of pictures. I oscillate back and forth between quick and slow approaches to my work in order to produce a spectrum of images.

Walk me through your artistic process in the creation of a piece.

The painting that I have been doing lately has been very malleable in terms of process. I know that the image is not going to end up as I have sketched it, but I like working through the composition that way. Creating some kind of rough composition is a good for me because then as I paint I can undo anything I don’t want to include. It gives me a certain amount of freedom that ends up producing a wider array of compositions. Tongue Tangle is a good example of a composition that was far more defined in the drawing than what has resulted in paint. The figure’s head was clear and his fingers were visibly in his mouth. As I got into it, though, it became more playful and less precious.

The larger pieces are really physical. Painting for me in general is a very physical activity. I don’t plan things out in advance but instead let the creative process take its course. I often just put nails in the wall, put a canvas on them, and work from there. Luckily, most of my compositions are wider than they are tall.

I don’t have a routine at all. I have a studio-based practice so I do feel the need to commit a certain number of hours a day to painting. I feel responsible to do work because I want to be productive, but I don’t schedule the time. I make work when I feel as though I have it in me and when thoughts are fresh in my mind. I also just set up another studio in South Hampton where I go on the weekends. It is something of a summer studio and I find it a lot more calming. The environment really affects the paintings, as we were talking about before. Most of the work will come back to my studio, in the end.

What is the summer studio work like?

There are some figural pieces and some more abstracted ones. There are also a few small black and white paintings that I have been using to explore my interest in abstaining from using colour at all — I am really into grey right now. Not using colour presents an appealing challenge for me because the work has to be interesting for reasons other than simple chromatic stimulation. My experimentation isn’t only about colour, however. I’ve also been adding text into my paintings.

Yes, I noticed that. What does the presence of text allow you to achieve with your work?

I think I have just been looking at a lot of text recently and felt the need to try it on canvas. Plus, the titles of my paintings have always been really important and I like playing with words. It felt like the right thing to try and find a place for words in my paintings, so the first places text showed up was in the form of body decoration: tattoos or cult engravings on peoples’ bodies. That carried on into stand alone text pieces.

You’ve been doing digital collage. In thinking of puns and text, one of the first things that comes to mind is the Cubists and their addition of news print and other written material into artwork. Do you ever consider making a physical collage?

Yes. I like the idea of incorporating other media however I also enjoy the limitations of keeping my practice to oil on canvas. It has a tradition to it that is fun to play with both conceptually and materially. I have never actually created tactile collages in the traditional sense, but it is something that interests me.

What is your primary focus right now? Is there a body of work that you are creating or do you work in a single-painting frame of mind?

If I am working on several paintings at once, there is often a thread of a theme that is carried on throughout but I definitely try to make every painting an autonomous body. If I notice a pattern in the paintings I am making, I will make a definite departure. It is always a challenge but I find it very exciting to work that way.

In terms of recent projects, I just put out a small book called Chiclet Teeth in an edition of 150 which made for a fun break from my painting practice. It has been circulating around a little bit and is sold on my website. It is self-published and sort of fits into the lo-fi aesthetic tradition, which I really enjoyed.

I approached the printer myself and was sent all of the proofs prior to the books being bound and sent to my studio. The process through which I went was really interesting and I am thinking of making another book with hand-altered elements. Perhaps digital work that has painting overtop of them.

I have returned to making new paintings, however, so will be showing them soon. Nothing definite, but I also don’t feel like I am in a rush. I am very motivated with the kind of work I am making so I am simply excited to be focusing on that.

Brian Kokoska Interview

appeared in CAROUSEL 28 (2012) — buy it here