From the Archive: Dash Shaw Interview (CAROUSEL 39)

“I wanted to be destroyed … and reborn.”

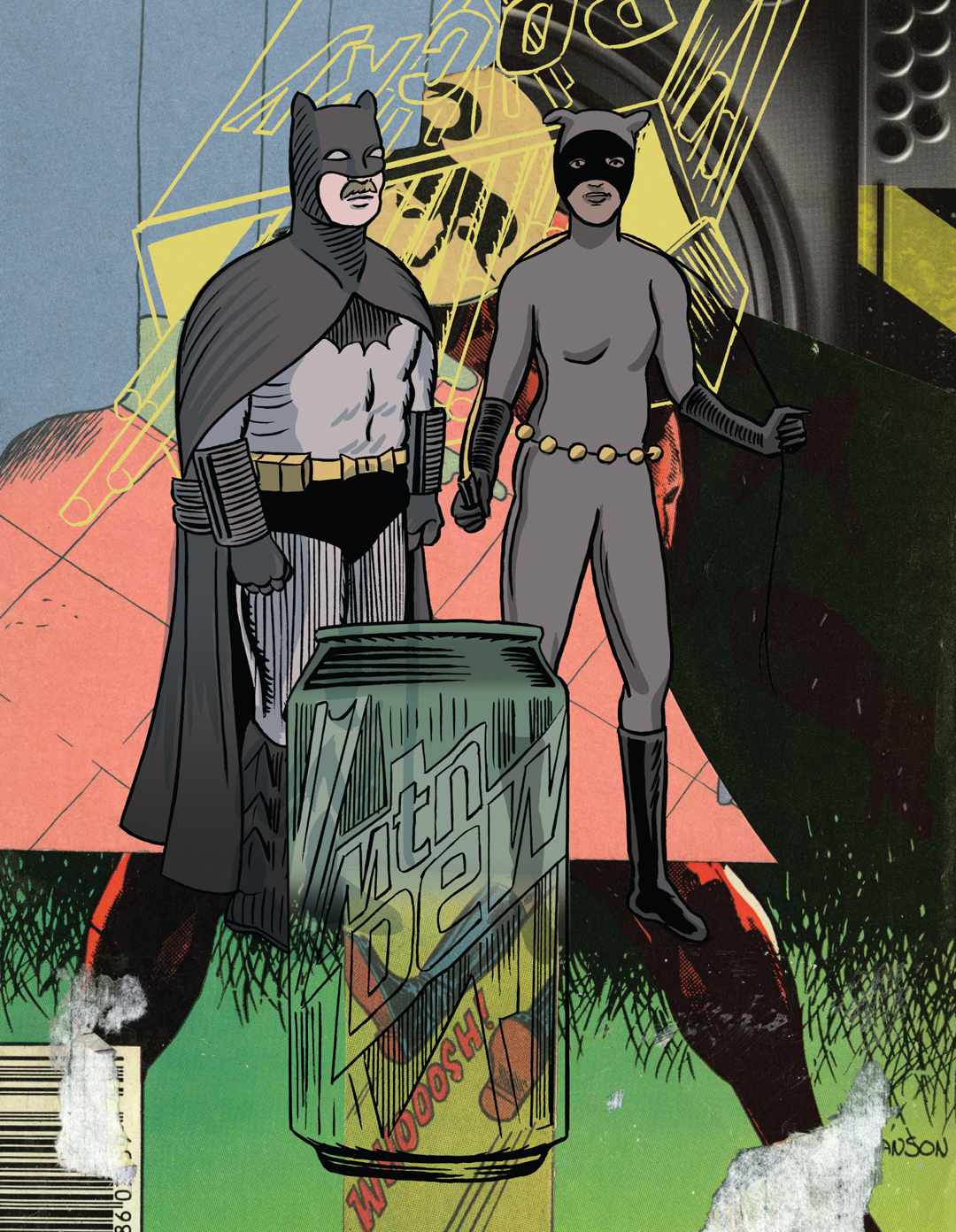

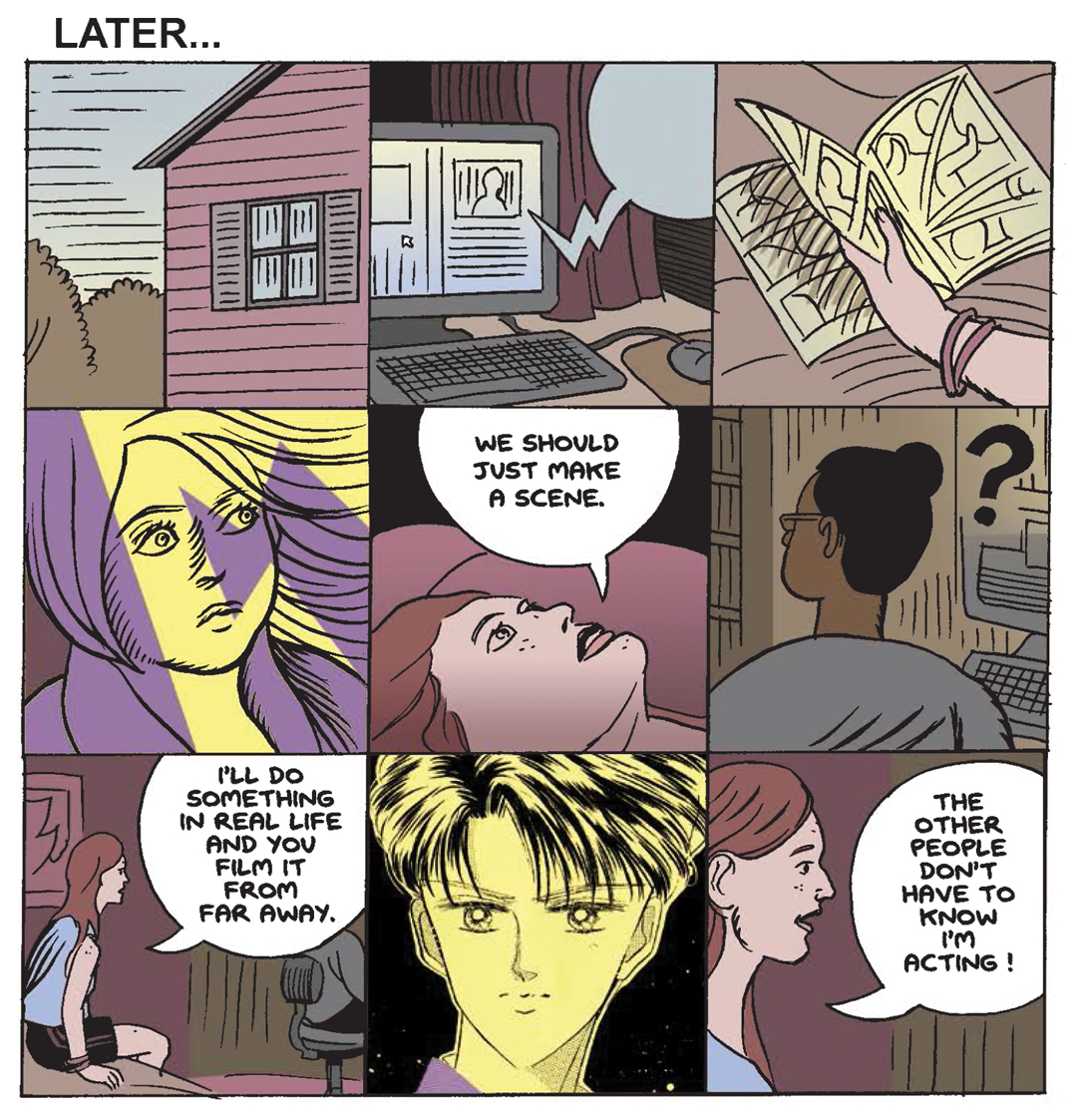

Dash Shaw credits these words to a tattered old comic book, near the end of Cosplayers, a recent collection of his own comics about fan culture, cartooning history, creativity, and female friendship. Shaw’s teen girl protagonists have lucked into a stash of funnybooks by the legendary Jack ‘King’ Kirby (1917–1994), co-creator of the Fantastic Four, Captain America, and, in this instance, the 2001 comic book adaptation. Heedless of the reverence that past generations have paid figures like Kirby, Annie and Verti — the convention-going, YouTube-posting cosplayers of the title — cut up and paste together their own collages from the King’s awesome imagery. It’s an ambivalent gesture, of a type Shaw has mastered: a moment that honours Kirby’s achievement at the same time it approves the young upstarts who ignore his importance. Tear it up and start again: it’s a method that’s served Shaw with each new project since the start of his career.

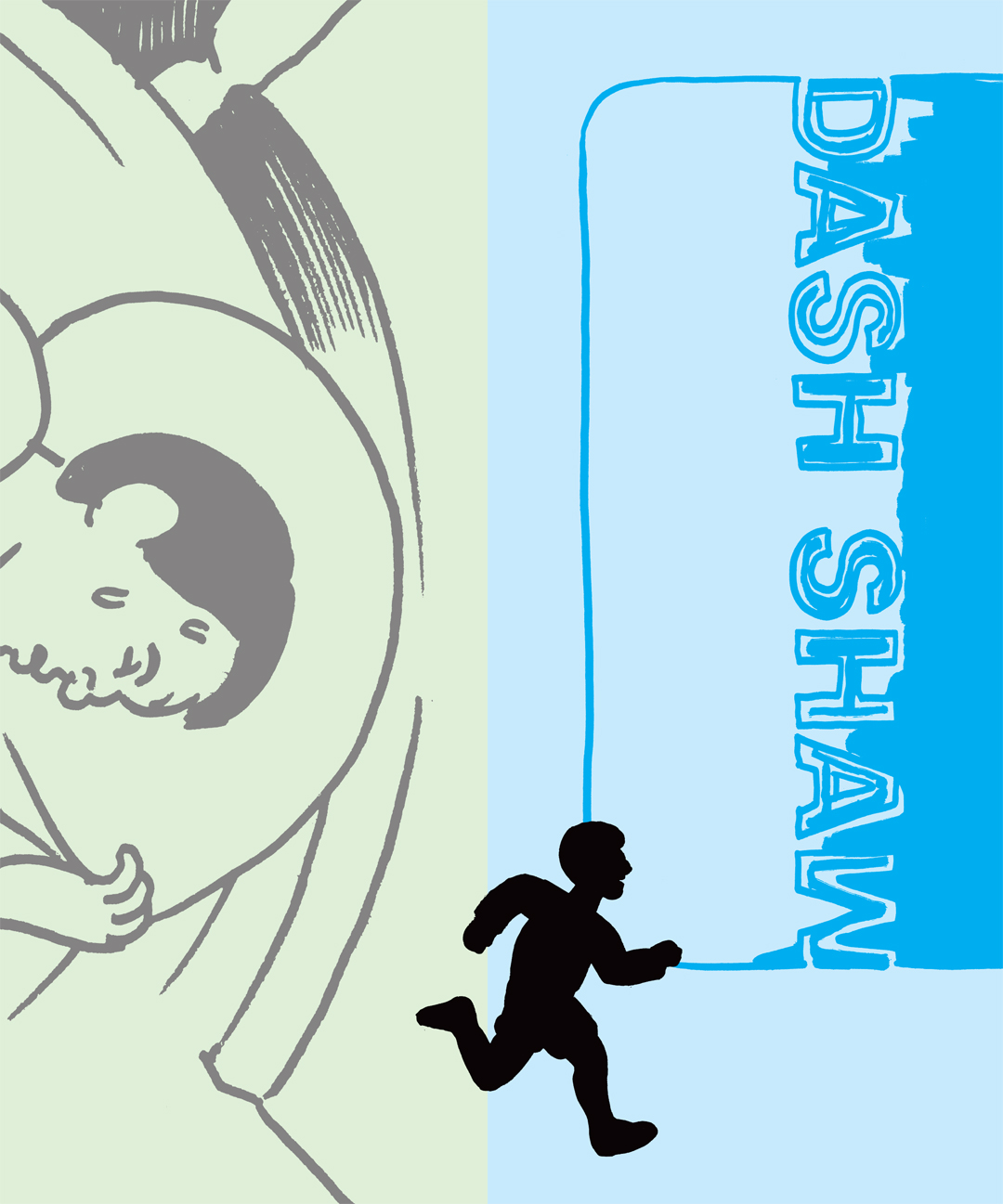

His breakthrough book, Bottomless Belly Button (2008), was a 720-page dissection of one family’s dysfunctions — the kind of hefty, sober, realist endeavour you’d expect from the shortlists of American literary prizes, rather than from a cartoonist still in his mid-twenties. Bodyworld, his next major work (collected in 2010), couldn’t have been more different. A gaudy science-fiction story about telepathy, published entirely online, Bodyworld reveled in its digital origins, its layers of hallucinogenic imagery and its endless scroll downward defying the bounds of pen-and-ink cartooning and traditional print culture. The graphic novels New School (2013) and Doctors (2014) would follow, their high-concept stories — about an avant-garde theme park, and a medical technique to revive the deceased — set off against jarring experiments in pacing and eye-searing colour.

Shaw also began to translate his drawing into animation with The Unclothed Man in the 35th Century A.D., a short series for IFC that ran in 2009. In his practice as an animator, Shaw champions the techniques of limited animation, the cost- and labour-saving method that gradually replaced Disney-style “full” animation in the postwar years by reducing the number of drawings required to make figures move. But Shaw’s work embraces limitation as an artistic choice rather than a budgetary necessity. In the deliberate stiffness and bare compositions of something like Charles Schulz’s A Charlie Brown Christmas, or his own haunting video for Sigur Rós’ ‘Seraph’ (2012), Shaw finds a capacity for deep feeling and zen-like poetry. “More comes out of it than was put into it,” as he said during a panel at this year’s Toronto International Film Festival.

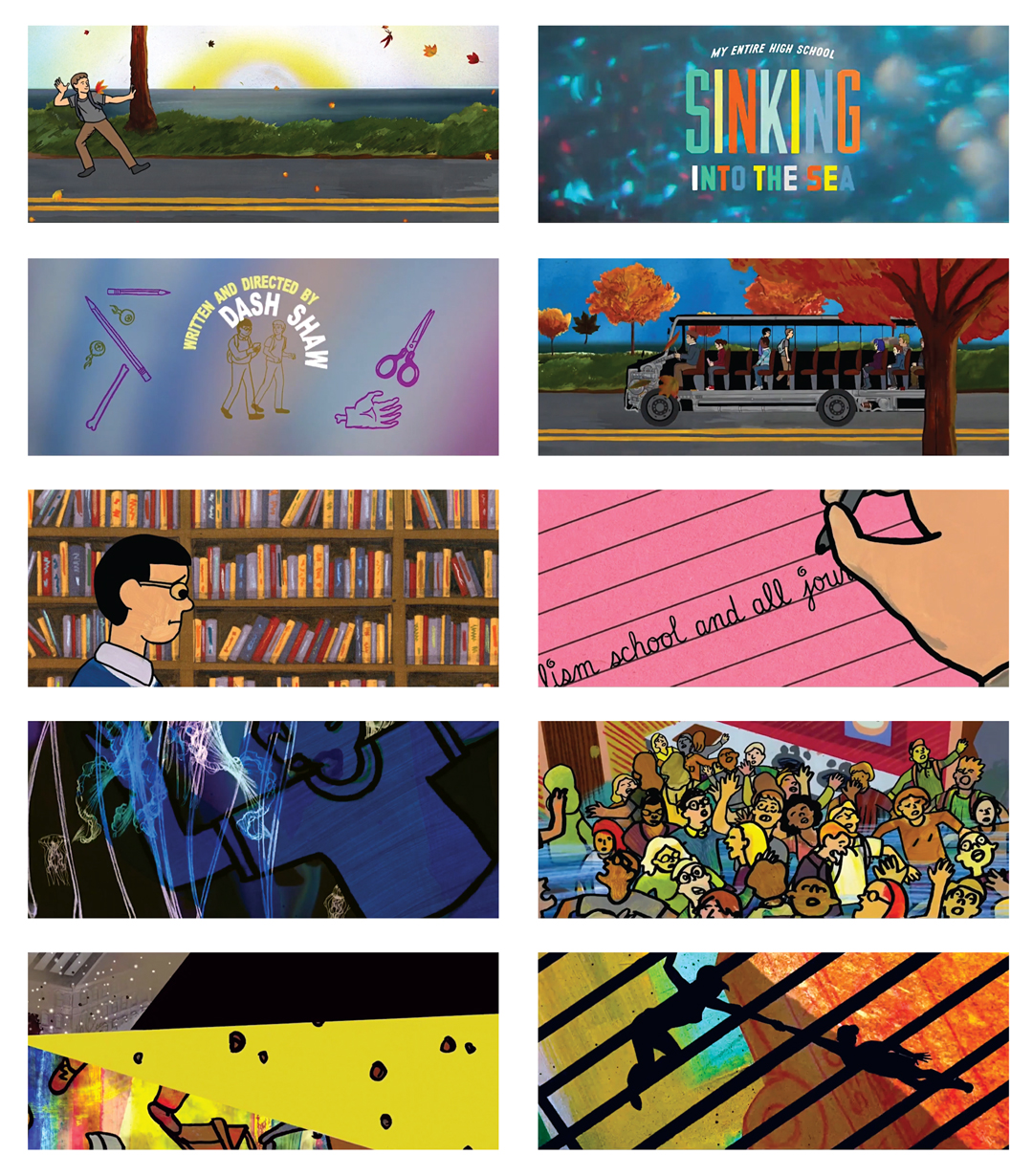

The artist was in attendance to premiere his first feature film, My Entire High School Sinking Into the Sea (2016). Adapted from his short comics story, High School features an ensemble cast of misfits headed by a teenaged “Dash Shaw” (voiced by Jason Schwartzman), who are thrust into survival mode thanks to their principal’s hubristic building-code violation. The seaside structure topples, flooding the lower levels, and causing quizzical bloodshed and chaos as students and staff try to ascend each floor and “graduate” to safety on the roof — call it a Buildingsroman. The film’s absurd action is comically underplayed, while its look is defiantly two-dimensional, jumbling flat figures together with photographs, cross-sections, overhead maps, onscreen text, and abstract, painterly textures.

Both Cosplayers and High School Sinking share a love of collage and pastiche, an admiration for their artistic precursors, and a complex attitude toward the subcultures and teenage protagonists at their centre. No matter whether comic or cartoon, Shaw’s work is drawn with chunky, clunky grace, coloured with abandon, and peopled with ranks of would-be gurus and wised-up kids — characters who make bad, dumb, hurtful decisions, but who try to find some kind of peace with the consequences. It was a pleasure to talk with him about his work.

Interview conducted October, 2016

Each of your projects seems like it builds on a new conceit, or takes a new aesthetic approach — something you’ve never attempted before. Cosplayers and My Entire High School Sinking Into the Sea are no exception. How do you match an idea to an approach?

The decision-making is intuitive, it’s not very conceptual, although I’m aware of how different lines and colours relate to pre-existing works. It’s like I have a story idea and then the next thought is, “well, what’s the most appropriate way to draw this story?” The story comes first; then the story will suggest how it should be drawn. It dictates the tools — like what pen to use, how it should be coloured, or its scale. I can’t change how I draw very much, but if I change the tools I use, the results can look radically different. Cosplayers is about people dressing as mainstream comic characters — so I thought I should “dress” that way too, by inking with a brush and computer colouring like they do in mainstream comics (and it was originally serialized as pamphlet comics, just like mainstream commercial comics are). My Entire High School Sinking Into the Sea suggested a very blunt, thick line that allows for abstract colouration, like a colouring book. The colours have a high drama that echoes the emotions of teenagers, and the thick lines remind me of Archie comics. This intuitive thought process is natural for me, even if it seems to be unusual when compared to other cartoonists. It’s just how I approach things. I can’t do it any other way.

Cosplayers finds value in a kind of handcrafted, do-it-yourself intervention into popular culture. How much of that spirit do you think carries over into your filmmaking?

When I first thought movies were cool, it was the nineties, during the American independent cinema boom. It seemed to me that the best stuff was happening in low-budget, D-I-Y ways — the most powerful things were being made by people with limited means who were figuring out how to get a lot out of a little. This was also coupled with an interest in anime created using a limited number of drawings — which felt connected to independent cinema, since the reason anime like Astro Boy, Speed Racer or Vampire Hunter D didn’t move as fluidly or as frenetically as other animated works was because they had lower budgets and were being made by smaller groups of people. So this connection between anime and independent cinema was there in my mind at a young age.

You’re present in My Entire High School Sinking Into the Sea as a character, but I wonder if there’s an autobiographical element to Cosplayers too? I’m thinking specifically of the scriptwriting scene, where Annie and Verti have to take this creative thing they’ve been able to do on their own and then professionalize it.

I had that experience — indeed, a lot of people have that experience, where they’re doing something on their own and then someone from the professional community brushes up against them. Sometimes the person is a real-deal gatekeeper, someone who can help get you into another, larger pop-culture world; but ninety-nine per cent of the time, they aren’t.

In the story, this guy says, “I’m producing shows for an online network,” but we don’t really know if that’s even true. We don’t know what this guy’s deal is. But he engages with them, and they think, “This person must be part of the popular culture machine, and we should be involved,” and it just ends up derailing them. I think that happens a lot to creators who are working independently; it’s almost like going through a grinder, where you come out the other end and decide either to stop or keep going.

In your characters’ case, though, it seems like they come out the other end rejuvenated. They realize that the thing they value in their work is their ability to control it and to be creative in whatever way that they see fit.

Yeah — that’s because as a writer, I want to have a happy ending! I think of all of the Cosplayers stories as being very positive. I could very easily have told a lot of these same stories with these same characters, and have it be negative; I wanted all of them to have a positive outlook.

I guess another way of coming at that is that line from Jean Renoir, “Everyone has his reasons.” I feel like that’s true of your work as well: in the movie, even the characters who are set up to be villains, like the principal or the lunch lady or the stoner bully, have attractive qualities.

I wanted the audience to like all of them. So even though the principal is sort of a bad guy, we really like him. When they reach the top floor gymnasium, we’re with these characters that we really like, even when they’re bratty and mean to each other. It has that feeling that I remember as a kid, like watching Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles — every scene in that cartoon, each character says a line; very goofy, completely unreal, but everyone would always have something that they would say. High School Sinking has some of that Saturday morning cartoon quality, where we like all of these characters, we want to see them go through these video game-like obstacles, including the bully and the principal. Near the end, when we know what all these characters are, what their shtick is, hopefully it’s more emotionally engaging.

Another bit of overlap between Cosplayers and High School Sinking, I think, is the significance of Jack Kirby and Osamu Tezuka, two cartoonists who also worked in animation. Why was it important to feature those two creators so explicitly in Cosplayers?

Well, I genuinely like them a lot — I have a personal engagement with both creators, and it just seemed natural to pretty explicitly talk about them.

I think that Kirby is up there with William Blake and other truly visionary artists, I sincerely believe that he’s on that level. When the comic shop owner is talking about how these 2001 comics altered his consciousness, I think that you can really get that from those comics. Whenever I had seen Kirby talked about, he was talked about in a kind of revered, fannish way, which I guess is what I’m doing too. I wanted it to be huge, kind of comically large: that reading these Kirby comics could alter your body, and make you stronger, and all of these things. I used this as an example of the power of comic books. Cosplay comes out of comic fan culture — you’re participating with these characters that visionaries like Kirby created; Kirby is giving you these tools that you can use in your life, and those comics can improve you as a human being.

And Tezuka is just so good at the mechanics of comics. He was the best at explaining complicated things very clearly and he was the best at creating comics sequences that were genuinely exciting. He invented a way of using lines on paper, and text and picture combinations, and composition and all these things to make a suspenseful scene suspenseful and a thrilling scene thrilling. There’s a reason why an entire country fell in love with him and, really, fell in love with comics because of him.

Is there any relationship between their work in animation and what you created with High School Sinking?

Tezuka is a bigger deal for me with regards to his animation work on the whole, and Kirby was a master of character design. With both these artists, as well as Alex Toth, you can see some of the tools learned from a life in comics being applied to animation. You can tell when Toth has storyboarded an episode of a cartoon because the compositions are way better than in other episodes. I liked that, and I thought, I can use what I know about composition and choosing particular body positions as a strength in my animated work. You can watch those early Astro Boy cartoons and see directly how Tezuka’s skills as a cartoonist translated to animation. It was a different approach than full, Disneyesque ‘squash and stretch’ style animation. I know there’s a whole school of animation that loves the Fleischer Brothers, and I see that there’s real beauty to that kind of movement. But in my mind, those Astro Boy cartoons are the gold standard of really beautiful cartoons. That kind of stillness in the limited-animation cartoon approach, it has a personality to it that I feel relates more to my own creative personality. The ‘squash and stretch’ thing is so wild and bubbly and everyone is overacting. Character’s mouths are going wide and their hands are swaying out in these exaggerated ways. But in the limited-animation approach, everyone’s more chilled out; there’s a stillness to it. It almost feels like experimental theatre, where the actors aren’t emoting in their faces, like something being directed by Robert Wilson. There’s simultaneity on the screen; everything is in focus, in this collage-like space. It’s the best.

So the vibrancy found in a Fleischer-style full animation doesn’t really appeal to you; instead, it feels like all the vibrancy and visual interest in your approach to animating occurs in the backgrounds. What purpose do backgrounds serve in your work?

I think of the backgrounds as being the main compositional element in animation. Because animated movies are drawn, the backgrounds can be anything — they can look like cubist paintings, anything; I don’t understand why they are always naturalistic. Miyazaki is a genius and his movies are so morally complicated and nuanced, but all of the backgrounds are like Maxfield Parrish paintings — pastel blue skies, white clouds, rolling green hills. Here’s someone who is operating on such a high level, through his stories and with his characters, and yet I still sometimes wondered, “Why does it always look like this?” You could scan any strange painting and put it on the screen as a background and it could be more interesting than just another carefully painted landscape. I always thought it would be really cool to see an animated movie that would have unusual backgrounds, ones that don’t have to follow the logic of space — I wanted to take advantage of that. This provides an opportunity for the movie to function abstractly. A viewer can follow the story’s main thrust by observing the characters, their movements and what they’re saying — I want people to be able to follow what’s going on — but there’s also an opportunity to view the work as an abstract experience, a formal experiment. I wanted High School Sinking to function on that level, too: you can follow the story, but also I’m giving you a light show, a spectacle. The kind of movies that I like best have that quality.

My Entire High School Sinking Into the Sea is one of only a few recent narrative works of animation I can think of that strives to make me see differently; other contemporary examples might include Studio Ghibli’s The Tale of Princess Kaguya (2013) or Ben Jones’ animated series The Problem Solverz. Do you feel like you’re more often working within a tradition, or breaking from it?

I really like comics history and reading artist biographies, and I like thinking about this giant trickling down of ideas. I think it’s cool how, when one group of artists are thought of as a break from the previous group, most of the time the new artists actually love the works of their predecessors. For example, if you think of the Pop Artists versus the Abstract Expressionists, a lot of people would say that they were a clean break; but we know now that one group were huge fans of the other group. It was a break, but also it was a continuation. Part of continuing is breaking, and trying to come up with different ways of handling things, ways that make sense in the now.

It feels like realism and fantasy swap around a lot in both Cosplayers and in the new movie.

Part of what I like about cosplay culture is that it does mix reality and fantasy in a cool way. These people are reaching into fantasy worlds, taking characters that they love, and trying to bring them out into the real world using sewing kits, fabrics and the tools at hand. I definitely love the translation that occurs when that happens; it’s where the excitement is. You see the way cosplayers are photographed, and they mostly strive to mirror the fantasy — they want to look just like Christian Bale’s Batman does. In Cosplayers, however, things are a little different: Batman might have a moustache, and his ‘bat logo’ might be a bit off. In High School Sinking, hopefully that tension is there too. In the story, all of this disaster stuff is happening — but Dash is still talking about acne, Verti is still focused on a friend who has stopped talking to her. There’s something real about fantasy and something fantastical about reality, and when you brush them up against each other those similarities or differences are heightened. It’s a more interesting space to be in.

Dash Shaw Interview

appears in CAROUSEL 39 (2017) — buy it here