From the Archive: Paul Carlucci (CAROUSEL 30)

PAUL CARLUCCI

A Lament for the Tetrapod

I see him through the windshield as I turn down our street. He’s standing on the lawn dressed in shorts and his Harry Potter shirt, staring at the grass, hands in his pockets. The rain is drumming off the car like fistfuls of baby hamsters, and the wipers swish back and forth, making my son look like a character from a flipbook. He waves when I pull into the driveway. A gappy smile and hair plastered over his forehead. There’s something irritating about it. Something I want to slap.

“Why aren’t you inside?” I ask him, the rain roaring around us. It’s the middle of the summer and the heat is cranked, like the two of us are sharing a hot shower. He doesn’t answer me.

One of his fish is flopping around in the grass at his feet. It’s the orange one with the big lump on its head, like a bulging brain covered in candy. All of my similes are infantile.

I grab his shoulder and give him a shake. “What are you doing to Bobby?” I shout over the din. The fish is gasping and floundering, completely oblivious to the irony of the rain.

My son points at the fish. “That’s not Bobby,” he titters. “That’s Iron Man,” and I slap him, my palm cracking off the flesh of his cheek. He grabs his face, looking shocked. Amazing how often a child is surprised by routine. “He’s just evolving,” the boy whines. “I saw it on TV.”

I say nothing, just head inside and let him learn what there is to be learned.

Later on, he locks himself in the bathroom, splashes around in the tub for a couple hours. I had four beers with dinner and I’m struggling not to piss myself. I’m knocking on the door and telling him to hurry up, but he’s ignoring me. I’m barking threats through the wood, but he’s unmoved. Amazing how often an adult is outraged by routine. I hurry down the stairs and tinkle in the backyard, the rain like pebbles at the bottom of his aquarium.

The next morning, I shoo away the neighbour’s dog. It was sniffing Iron Man’s corpse. As soon as I pull out of the driveway, the dog trots back to gobble the fish.

I can’t focus at work. My anxiety is sky-jacked by coffee. I shuffle my paperwork and wipe my desk. There was a photo of my son and my ex there once, but I threw it out after she left, frame and all. I stare out the window and look at my car in the parking lot. It’s a four-door sedan, ugly brown like crayons, and rusty too. I’ll never remarry if I don’t replace it.

My phone rings. It’s my boss calling from head office, reminding me I’m supposed to identify thousands of dollars in departmental budget cuts. I tell him I’ll be done by five, but I’m staring at the line items like I’ve never seen them before. It’s hard to care because I’ll never remarry with this salary, with these benefits, with my pension. There’s nothing here for me, and sometimes I worry there’s nothing for me anywhere else. I miss the cocaine I did in first year, my life blissed all the way out, a thousand Toronto tomorrows.

I make cuts at random. I close my eyes and drop my finger on the line sheets. No more coffee in the break-room. I do it again. Half the toner for the photocopier. I open my eyes and I’ve slashed a whole position, a full-time gig at the front desk, some college grad with no tits and huge glasses. She doesn’t stand a chance out there. The lions will pick her off like a slow gazelle in a Disney documentary. Her life is not my problem.

After work, I drive to the Yorkdale Mall to meet Richie. He always wants to meet in the food court. It’s meant to insult me. I see his Porsche Cheyenne outside the mall and take the space beside it. But then I change my mind and drive to the other end of the parking lot. I’m not here to dole out that kind of satisfaction.

I’m torn between Starbucks and Tim Hortons, knowing that Richie can see me from his table in the food court, the newspaper spread out like disposable placemats. I watch him out of the corner of my eye. I notice for the first time that he looks just like her, that delicate nub of a nose, that curly brown hair. His jaw is v-shaped and feminine, something out of the art house films we watched in college. He’s wearing tidy jeans and a black sweater, all dressed down for a thousand bucks.

The barista is a delicate little thing, Asian, her bangs shot through with purple streaks. She’s typing on her cell phone, head down, chin above the apple-bulge of her breasts, across her apron that ridiculous, semi-psychedelic coffee logo on her apron, that mermaid with the crown, jazzed on beans, her hair like serpents.

“Just a minute,” she says without looking up.

“Is that your boyfriend?”

Her shoulders tense and I place my order, rattle off a series of modifiers that begets some fleck-foamed creation I can’t normally afford.

“You look like a woman with that thing,” Richie says when I sit down.

“Funny,” I tell him, “I was just thinking something similar about you.”

He folds his hands on the table, like opulent paperweights, manicured and bejewelled, spoiled only by a slash of mustard dried to one of his cuticles. “How’re things at home?”

I sip my foam, see him bite back a smile as I lick an excess off my lip. “Sometimes I wish she had taken him, too.”

“Easy. That’s my nephew you’re talking about.”

“If he means so much to you, why don’t you come by for the occasional visit?”

Richie leans back and gives his head a tiny shake. The curls above his forehead vibrate ever so slightly. “You know why. I don’t want to confuse him.”

“You’re so thoughtful.”

“Don’t be smart.”

I imagine that the barista is staring at me, wondering about me, divining the emerging tone of my shoulders through my suit blazer, hearing me grunt at the foot of our bed while I pummel through my push-ups. Her hair turns to serpents. She’s jazzed on beans, a deep sea goddess, a high-pitched whale-call, my wife gone forever.

“Have you heard from her?”

“You’re not supposed to ask me that,” he says.

“Why not?”

“She wants you to move on. We all do.”

It’s impossible to find the coffee beneath this foam, and I notice that Richie is drinking a large double-double from Timmy’s. It’s more of his bizarre braggadocio. Even when he spends low, he consumes high.

“So,” I say, “what’s up with the property?”

He unfolds his hands and drums his fingers on the table. He sips his coffee and tilts his head, regards me pityingly, says nothing, the inane chatter of the food court filling the silence between us.

“Richie?”

“I heard you,” he says. “It’s not polite to rush business.”

“But I am in a rush, Richie. You know that.”

“I do know rush,” he nods, “probably better than you. This rush you’re in, it’s entirely self-propelled. There’s nothing rushing you out in the bigger world.”

I snort, disgusted. This is Richie’s philosophical bit, his seasoned sage thing. I’ve been hearing it for years.

“Remember,” he says, “when we went to the beach that night after last call? In first year? We couldn’t believe how big the surf was for a lake. We kept thinking it was like an ocean shore. Remember that?”

I give him a tight nod. The less I say, the sooner this will pass.

“Remember how you rolled up your jeans and ran out into the water?”

Another nod, the smallest dip of my chin.

“The fish?” he prods. “It was caught in the shallows and you hurled it back in.”

“Richie, can we talk about this another time? I need to know what’s going on with the property. I need to answer to the bank. I need paperwork. I am in a fucking rush.”

He puts his elbows on the table and leans forward, his chin resting on the mounds of his knuckles. “Right. The bank. Sometimes I forget.”

“Not exactly self-propelled, is it?”

“Well, I don’t know. You did take out the loan.”

“What’s happening with the property, Richie?”

He sighs, condemning me to bad credit, garnered wages and another crippled ambition.

“They decided against us?”

“The municipal board was impressed with the heritage department. They like stuff like that, you know. They like five-bay estates formerly owned by captains of national industry. They like to imagine one of them sauntering down the gradient with a pipe in the corner of his mouth, looking out on the lake, watching the yachts tip by.”

“Jesus Christ, Richie.” I choke back a sob. “Is it over? Are you saying it’s all over?”

“I’m saying this project is over. They won’t subdivide that lot. I’m saying what I told you from the start. I’m saying you shouldn’t invest in the early stages, the planning and designing. Leave that to the rest of us. You come in when there’s a shovel in the ground, when things are evolving.”

The foam has broken up in my coffee, its wispy, bubbly vestiges clinging to the side of the cup, spinning idly on the dull, brown surface. Sea scum.

“But you took my money, didn’t you?”

“You pressed it on me. I told you the risk was high, but you were in a rush. You didn’t listen to my advice. I figured you’d either get away with it, make yourself a return, or you wouldn’t, and then you’d learn a lesson.”

I can’t listen to anymore of this. I stand up fast, make a split-second decision to bump the table on my way up, rock it with my knee, watch in spiteful anticipation as my coffee splashes over the side, soiling the paper, as the cup tips one way and then the other. But Richie calmly reaches out to steady it. He gives me another of those pitying smiles.

“Go home and be with your son,” he says. “Look over your finances. This probably isn’t as bad as it feels.”

I float through the food court in a trance, passing by the Starbucks on my way out, casting a glance at the barista, who is absorbed in her cell phone. I pull out my phone and point it at her, find her in my viewfinder, oblivious as she natters. I take her picture. My screen freezes for a moment, and there she is, talking to her boyfriend, head down, like a modern version of The Thinker, upright with full reception, possessed only by the gratification of association. My similes mature.

I sit on the couch, the TV off, a beer bottle stuck in my crotch, financial paperwork stuffed in an accordion file sitting on the coffee table next to a pizza menu. The walls are full of hooks that used to hold pictures. I sit there for a long time, drinking slowly, swishing every sip around my tongue until it’s warm and flat and disgusting. Then I swallow it.

“Dad?”

He comes into the room with his hands behind his back, still wearing his Harry Potter shirt, still the same shorts. There’s a blotch of red by his temple, from where I slapped him, and I realize I’ll have to stop that when school starts next month.

“How long does it take?” he says, looking at the table.

“I haven’t ordered yet.”

“Not that,” he says, and he walks closer to the couch, stops at a safe distance, about arm’s length. He shows me his hands, a dead fish in his palm. “This one’s Bobby. He didn’t change either.”

I reach for my beer and he flinches. “It takes forever,” I say. “Like millions of years. You won’t live long enough to see it, and you wouldn’t notice even if you did.”

His mouth shrinks into a tight and tiny detail, like a line item, and I consider cutting him. He leaves the room and I hear him walk upstairs and run the bath, the tone of falling water becoming deeper and deeper as the tub grows fuller. It’s futile, obviously, because there’s no bringing Bobby back. But I don’t run up there to tell him. Better he learn himself.

•

A Lament for the Tetrapod

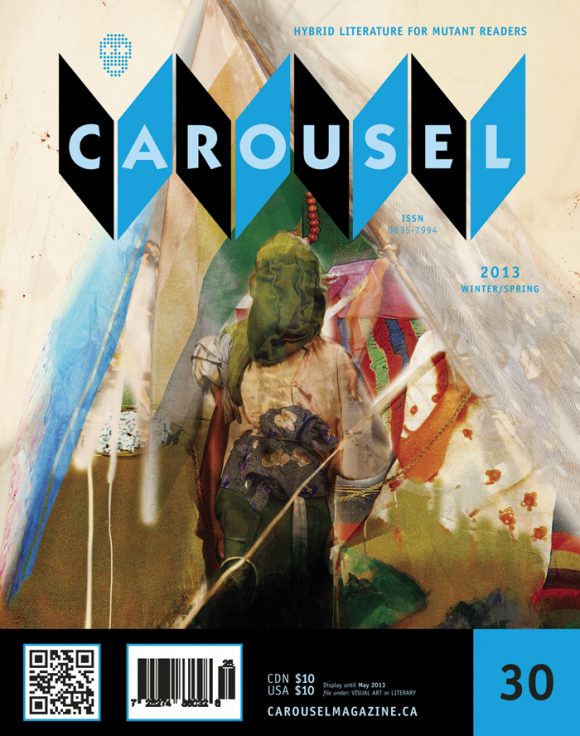

appeared in CAROUSEL 30 (2013) — buy it here