USEREVIEW 004: Living Violence

John Nyman follows the mine shafts of Klara du Plessis‘ book of poetry Hell Light Flesh (Palimpsest Press, Sep 2020) and reports back on the glistening subterranean horrors he finds there. This traditional review examines the unsettling juxtaposition of artistry and rationalism with the terrifying triad of patriarchy, violence and trauma.

ISBN 978-1-989287521 | 130 pp | $18.95 CDN / $17.95 USD

#CAROUSELreviews

Enormous in scope yet sharply-defined in subject, Klara Du Plessis’ second full-length work is a serious and strikingly beautiful study of the impacts of physical child abuse. Explicitly, Hell Light Flesh spotlights an unnamed son of two artists whose family life is haunted by his father Maria’s beatings. Yet the book is remarkable not only for its direct confrontations with trauma and patriarchy, but also for its willingness to bear out their implications through the subtlest aspects of its form. Driven by this commitment, Hell Light Flesh reveals Du Plessis as a master of contrast in image, language and thought, evoking a terrifying cosmos of concepts even as it confines itself to a claustrophobic paucity of domestic spaces and scenes.

From the first lines of Hell Light Flesh, Du Plessis hones in on how fear, violence and authority persist as affective presences even when they are not concretely there. This emerges in the book’s opening sequence, ‘We Are Afraid,’ via the speaker’s panoptical feeling of being watched as he ascends the stairs to his father’s studio:

My footsteps cast shadows

climbing.

I can feel his eyes on my back,

uncertain if he’s turned away.

On its own, this short passage profits from many of the key features of Du Plessis’ style: an emphasis on the organic tensions within imagery (“shadows / climbing”); sensory blending (“feel his eyes”) and an ambling, trepidatious rhythm fixated on back-and-forth movement. What most gives ‘We Are Afraid’ its distinct texture of fear, however, is not individual moments but their seemingly endless extension — across untitled pages of fresh musings that nonetheless circle back to the same rot. Du Plessis’ speaker waits and waits for Maria to follow up on his inaugural command (“That’s it. Upstairs, / immediately!”) and meet him in the studio. As he’s waiting, nothing happens. But he has no choice except to keep waiting, and the terror only grows:

If I keep an eye fixed on the door,

how will I see what’s inside the drawer?

Maybe a quick oscillation

between door and drawer,

[…]

The negative space of the wooden box

slides towards me, as I glance at the door,

then down. The void

rattles, leading me to the next of a series

of three, all empty.

In a way, the sequence takes on the structure of a bad joke: all the build-up couldn’t possibly be justified by whatever happens at the end. Indeed (spoiler alert), nothing happens at the end of ‘We Are Afraid’: the anticipated beating is indefinitely deferred.

Still, the better joke comes on the page quoted above: “My father, the upright man, / empty drawers, but well hung.” The Freudian slip isn’t for nothing, as Freud insisted that the fear of castration played a far more important role in psychic and social life than the phallus itself. Hell Light Flesh, too, insists that the threat and shadow of patriarchal trauma is overwhelmingly real, to the extent that the patterns and prisons of the mind that it engenders persist despite the fact of the father’s absence.

Hell Light Flesh is best understood as a long poem, although it is neither a narrative epic nor an extended lyric. Instead, the book’s sections — which are occasionally titled but usually separated wordlessly by page breaks — feel like scenes in a play, or even rooms in a house. Their rhythms and pacing regularly borrow from those of monologue and oral performance. Other times, they draw from essayistic prose in their focus on precise yet plainspoken truth telling.

Eschewing concision, Du Plessis’ poems carry on gradually, as if pausing to make sure their wording is right. They often say things that one feels don’t need to be said, as in ‘Hand,’ which outlines material and ethical conditions for corporal punishment. These effects add up to an eerily palate-cleaning thoroughness from which Du Plessis’ richest poetic gestures resonate, like the word “twisted” in “a boy whose head is twisted / beneath the disciplinarian’s / arm.” Held taut at all ends, Du Plessis’ verse maintains a ground of sustained attention upon which its formal accomplishments stand tall.

And those accomplishments are many. Among them is the effortlessly convincing characterization of the book’s teenage speaker, whose precocious intellect is balanced by his flaccid send-ups of the hypocrisies of the world (“I will do better till the next time I don’t do better”) and equally flaccid dreams of escaping it (“leaving behind this inconsiderate life”). Du Plessis is also a master word painter, particularly when she embraces (though always roughly, with a kind of frantic passion) the stranger connotations of her language:

Boughs round out to the sides

in equal proportions

from a mid-point of symmetry

where reverse eyebrows

sigh up to the divine.

Thin grey branches deign

development, density,

the centrifugal stem,

metaphysical whips

perpetrating crimes to the air —

material scoops of sky

ladled into themselves.

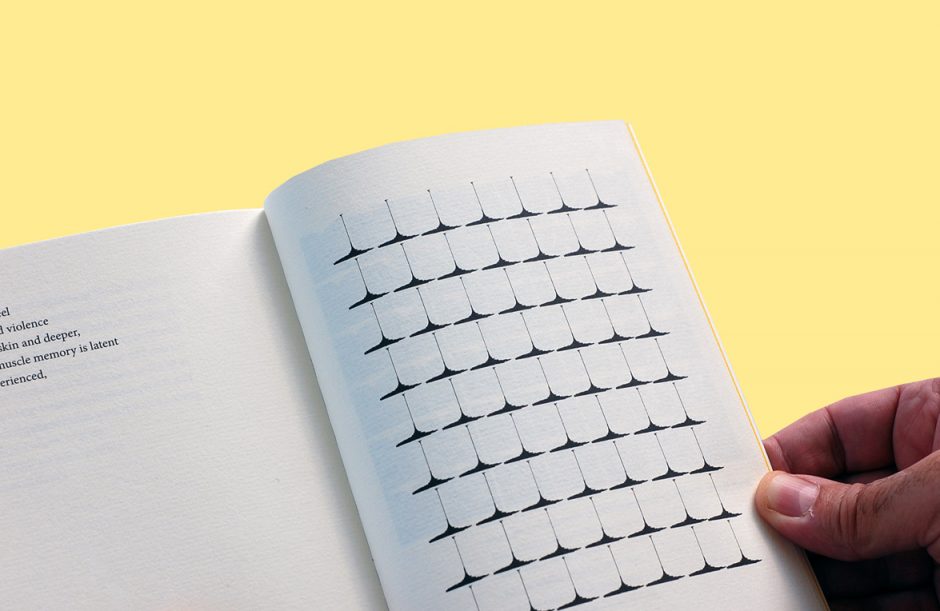

Yet even these moments of exquisite, crystalline beauty cannot escape Hell Light Flesh’s cynicism; in fact, they reinforce it. Du Plessis argues that both the detailed attentiveness of art making and the ornate cavities of our darkest desires are consistent with the stalwart architecture of the (father’s) law. These themes spiral into a synaesthetic thread that is also reflected in the book’s use of experimental form. While her engagement with asemantic poetics centres on a series of black and white adaptations of the visualized sound of a belt hitting flesh, Du Plessis also exploits wordplay and homophony to ratchet up her verses’ pitch. In an especially poignant moment, a one-and-a-half-page-long alphabetized list of phrases starting with the word “double” begins, in its relentless repetition, to itself sound like the belt:

He slips leather off the wall

and doubles it

double act

double agent

double axe

double back

double bed

double bill

double bind

double bond

double book

double check

[…]

double U

double vision

double whammy

Despite its articulateness, Hell Light Flesh remains relatively agnostic about the larger patterns behind the experience it describes. That is until its final pages, which narrate its speaker’s spectacular convergence with the tradition of patriarchy:

I am my body, I am hurtled

through violence, I partake

in a tradition of violence,

[…]

I think of the violence done to my father,

to his father,

I think of the violence

I will do to my son

and it becomes a tenderness,

a passing on, hissing through my teeth,

this patriarchy which is my body

Du Plessis’ speaker’s attitude reveals a paradox that has often given me pause. Why, when even a teenage boy can see and feel the baselessness of patriarchal violence, do men continue to participate in it? The problem only compounds when I consider Maria’s intense creativity and rationality. Despite his almost total absence from the events of the book, I imagine him having thought through these themes in greater depth than his son could even imagine.

I don’t think Hell Light Flesh offers an answer to my question, although I’ll take it as a sign of the book’s power that it invites the following guess. There is no cause to sympathize with Maria — and yet, within the book’s sphere of masculinity, there is no one else to sympathize with. That’s the trap. When thinking through our conditions only casts doubt on the possibility of changing them, we become inclined to defer to those who have thought about them longer and harder. In the process, we fail to live differently. Or, as Du Plessis’ speaker suggests, we “substitute / living with thinking.”

This thinking — rational, aesthetic, sensual — is also the very stuff of Hell Light Flesh’s tone and take on the domestic universe it brings into being. As such, the kind of life this thinking recruits us into, that patriarchy recruits us into, cannot dissolve within the book’s pages. What Du Plessis does instead is make it glisten, as if increasing the resolution of a blurry photograph.

To see more clearly a problem for which one sees no solution may be deeply unsatisfying. On the other hand, such dissatisfaction is also constitutive of survival in an unjust world. It is a meaningful dissatisfaction; in a sense, it feels right. There may be little else to do, then, but to commend Du Plessis for her incredible attention to its contours and hue — and to let that attention linger a little longer.