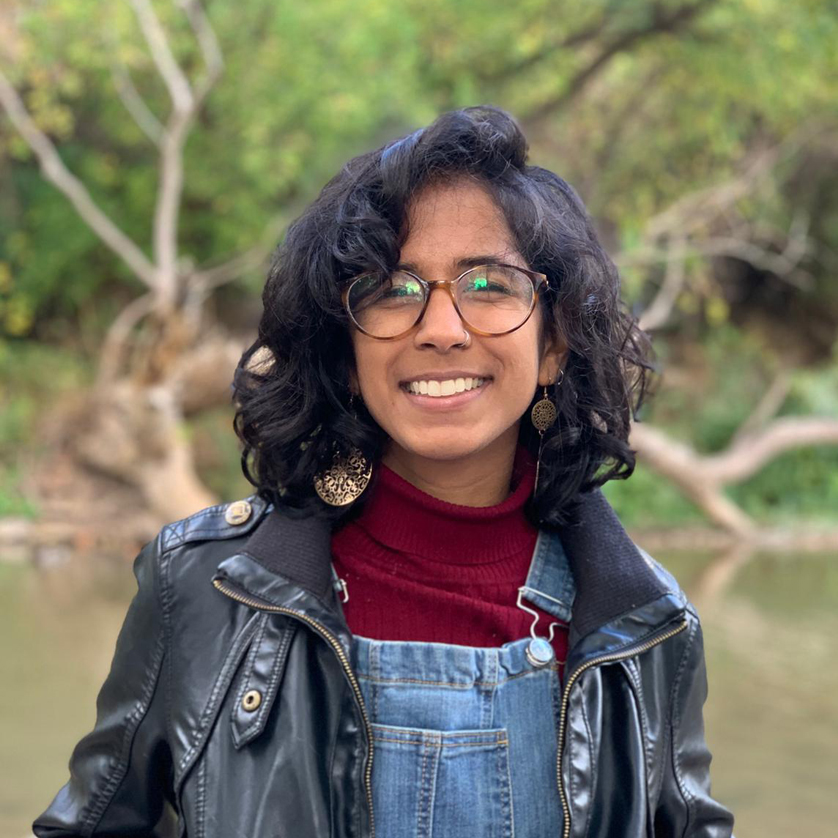

USEREVIEW 007: Do You Want to Dream Without Falling Asleep?

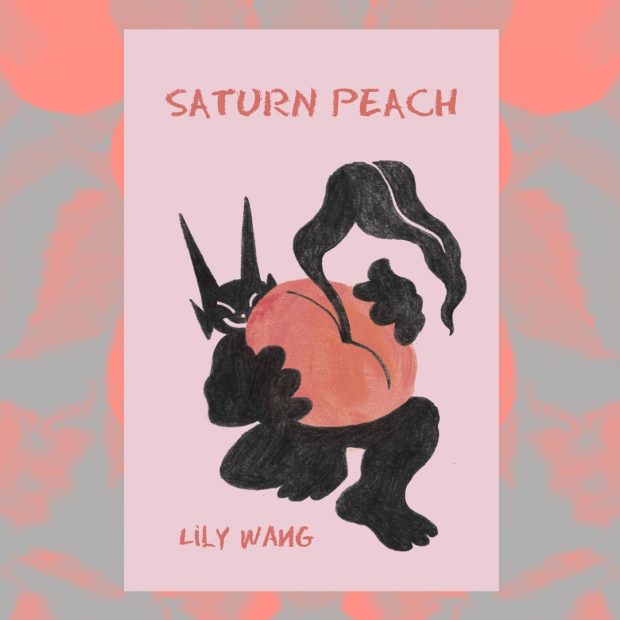

Bodies are ever-shifting in Lily Wang’s Saturn Peach (Gordon Hill Press, 2020). At times they assume forms sweet as peaches, at others they take shapes treacherous as caves. In this traditional review, Manahil Bandukwala acts as skillful psychopomp, guiding the uninitiated through the blurry waters of reality and dreams that make up Wang’s debut poetry collection.

ISBN 978-1774220115 | 86 pp | $20 CAD

#CAROUSELreviews

There are certain Tweets by Lily Wang that I think about often. “Mosquito bit the side of my cheek…. that’s not for you to kiss!” posted on September 13, 2020; “think i’ll start carrying a q-tip around and pollinate flowers,” posted on August 7, 2020. Saturn Peach is like having eighty-six pages of Lily Wang Tweets to read and think about. That is to say, her words linger. They layer emotions in the unsaid. They question.

Reading the poems in this collection is like entering a dream state. Wang demonstrates her striking ability to wield syllabic structure to produce a surreal affect in both her prose and lyric poems. From short lines cut off too soon to long lines that swerve between different images, there is no telling where each poem will go next.

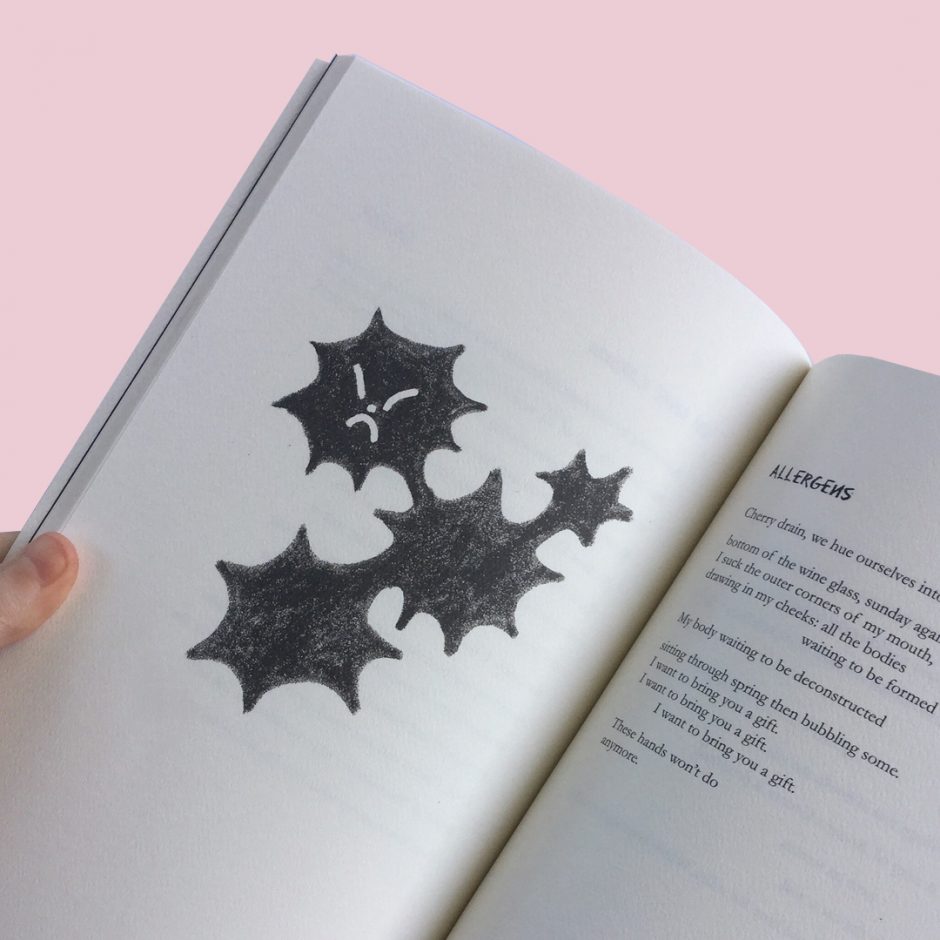

The collection is divided into five parts and interspersed with crayon-style line drawings. Each drawing, whether it is of a flower or a knife point or an egg, has a small, minimalist face. What do these drawings say? Perhaps nothing. Perhaps everything. But mostly, like the poems, they ask the us to step out of our bodies for a brief moment.

A small prose poem acts as preface to the book. “I am rowing away from myself into myself. In a dream where I decide everything. I decide I am edible. I decide to eat a peach. Reflections on the snow. The water Saturn,” writes Wang. The fragmentation of sentences cut off too soon acts as a door into the dream that is Saturn Peach. Dreams (or, at least, my dreams) are flashes of random images thrown together that inextricably make sense. The peach, the snow, Saturn.

Do you want to dream without falling asleep?

Wang is not afraid to get absurd. In ‘Magic Hour Confessions,’ she writes, “I want my favourite poets at the animal ball. Richard Siken gets to dance with the zebra because he makes me cry the most. Anne Carson spikes the punch. She’s got the quickest hands and there’s 13 of her.” Within the same poem, there are moments of hilarity brought sharply down to a melancholy reality. Amidst this joyous animal ball, the speaker finds themselves seemingly alone. “It’s such a funny story and the best part is no one ever remembers except for me, so I can tell it over / and over legs crossed, dress wide on the staircase, tapping my feet.”

How do you show loneliness without saying the word “lonely”?

Perhaps what makes the poems so heartbreaking is Wang’s ability to depict an anxious internal state of waiting. In ‘We’ll Make a Deal,’ she writes:

I’ll reach for my phone to ask you what page you’re on but I’ll grab the remote instead. I won’t hear from you so I will play it from the start.

I won’t hear from you.

I’ll play it from the start.

I won’t hear from you.

I’ll play it from the start.

There are no loud moments of fighting and anger that descend into a split between lovers. The speaker does not want to be overbearing or overeager. How do you discern between the other person wanting space and the other person being sick of you? Can you? The speaker wants to be understanding. The speaker is left waiting, alone.

What is the heartbreak of waiting?

Wang asks,“if your heart was a fruit what would it be?” What forms do we inhabit? What forms do we inhabit when in love? From Saturn peach to yellow plum, the poem ‘5’ from the collection’s second part sits on the line between love and heartbreak. Wang breaks down the requirements of having a form: teeth, a pit, the ability to be held. “Can I be a tree,” she writes, making a tree into another fruit you can sink your teeth into. I ache with the speaker of the poem. I ache at the lines, “The moon is gibbous and people are dancing on the street. / Sidewalk salsa, how romantic, how simple, how perfect.” Wang skillfully hides meanings and emotions and yearning under words. Everything is full of yearning.

Part three undertakes further explorations of form. In ‘There Came a Great Buzz,’ Wang opens with these arresting lines: “What if you are full of mosquitoes?” The question is terrifying at the outset, but through Wang’s surreal and delicate imagery, becomes almost comforting: “When the sun set water covered my pupils, because we were by the shore, everything condensed. Behind my back, there was a cackling, a fire, and one by one the mosquitoes flew out of me.” Against the calm of a fire by beach, strangely, I miss the mosquitoes.

How do you differentiate the mosquitoes from the rain?

In ‘Buzzfeed Predicts my Breakup,’ Wang weaves poetry and Twitter together. “A few weeks later he will send me his novel manuscript. He’s so @GuyInYourMFA,” she writes in a phrase that is familiar to those in the Twitter poetry community. There is a blur between the archetypes of the Poet-on-Twitter and the Poet-in-a-Book. The poem concludes with the lines, “Buzzfeed says I will reunite with my tenth-grade crush. I want to know the calamities,” capturing the hugeness that is existing in an Internet age of Guys-in-your-MFA and quizzes that tell you what kind of breakfast food you are. It is all a calamity.

The want to be wanted enters strongly in part four. In ‘Allergens,’ Wang writes:

My body waiting to be deconstructed

sitting through spring then bubbling some.

I want to bring you a gift.

I want to bring you a gift.

I want to bring you a gift.

These hands won’t do

anymore.

The form of the heart as a fruit or the arms full of silence is no longer enough. What will be enough? Wang definitely wields an impressive skill with repetition, employing tools such as spacing to drive home the longing behind repeated phrases.

A huge part of the wonder and joy of experiencing Saturn Peach is that it demands a surrender of rationality. ‘Some Trees’ is a small poem tucked into part four. It starts colloquially, but in a way that is very Lily Wang, offers a delicate yet heavy glimpse into the distinct worlds of “I” and “we.” The poem closes with the lines, “There are still / many flowers I haven’t learned to name. / I bring them to you: my arms / full / of silence.” The act of naming things intertwined with the act of giving form to things weaves in and out of this collection. Choosing the fruit the heart would be parallels choosing names for flowers.

Without a name, what is the form?

As the back of the book promises, Saturn Peach is part heartbreak, part wise witness. The fifth and final section brings forth a sense of hope amidst ache. In ‘This Year,’ Wang writes, “maybe every year it gets harder, maybe every year it gets brighter…maybe this, maybe this is the year.” Reading this in a time when it can be hard to imagine the year getting brighter, there is a signal of some hope. Even if that hope ends up not being fruitful, it is something. Flowers on a snowy day or shoes worn out. You will not always know what each metaphor means, but you do not need do. To read Saturn Peach is to relinquish control and allow dreams to take over. And sometimes, that is exactly what you need.