USEREVIEW 013: Tiny Ruins of Reality

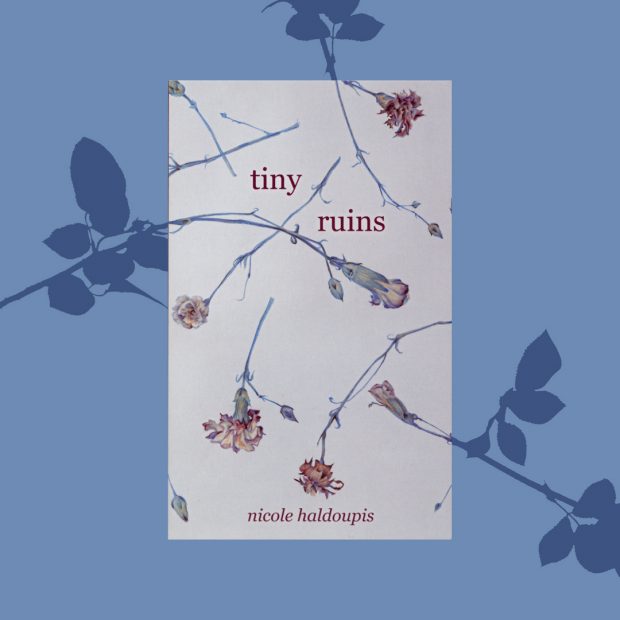

Conyer Clayton assembles the fragments of narrative in Nicole Haldoupis’ Tiny Ruins (Radiant Press, 2020) to construct and construe the themes of surrealism, memory and queerness in this traditional review of a debut flash fiction novella.

ISBN 978-1-989274385 | 88 pp | $20 CAD

#CAROUSELreviews

#USEREVIEWEDNESDAY

Tiny Ruins, Nicole Haldoupis’ first book, is a novella built through flash-length (usually one page or less) stories; snapshots that create a somewhat jolting, and effective as such, sense of time. There is clear linearity but within that there are leaps, gaps, fragments — making each story have a function similar to memory. We do not remember every moment of our lives with clarity. In fact, the ones we remember are often somewhat puzzling. The insubstantial. Tiny Ruins feels somewhat like the telling of a portion of life in third person by what that person would remember in old age.

Tiny Ruins feels as though it lives on the edges of surrealism, despite being firmly rooted in the real. Perhaps this is because of the gaps intentionally left that allow the reader to make their own assumptions, to surmise about what passed in the space between vignettes. Or perhaps the sometimes plain-spoken and sparse nature of the prose lends itself to the feeling that something is being evaded, spoken around. Or perhaps it is the very magic of time-passing itself that these gaps beckon towards, leaving me feeling as though there is something brimming just beyond the outlines of the story, of the things we as readers are allowed into. This isn’t to say that the storytelling feels withholding, quite the opposite in fact. It looks honestly into extremely intimate and embarrassing moments of Alana’s adolescence and young adulthood, and her relationships with other women: her mother, her sister Janie, and a friendship but also hidden love and lust for her friend Sara. This feeling of something just out of sight, the questions of what is between each story, are a strength. This is a book that doesn’t give it all away, leaves you wondering what happened then, and then, and then, which I found to be a quite effective stroke of craftsmanship on Haldoupis’ part.

Some of my favourite moments in this book were the ones that leaned into this fragmentary feeling, the “why do I remember that” moments. These often are related to fear of aging, decay and death. In “Flowers,” a very young Alana wakes up in in the middle of the night and goes to her mother’s bed. She says:

“Mama I don’t want to get reborn as a flower or a bee or anyone because then you wouldn’t be my mama” and her mother touched her face and said “Oh sweetie” and Alana cried and her mother carried her back to her bed and she fell asleep, as if it never happened.

Alana’s preoccupation with death and being reborn continues throughout her adolescence. In “Live in There”, she “watched an ant climb into the fire, stop, change colour from black to red, and burn. She wondered what it’d be like to live in there.” In a scene from “Black Hole”, Alana calls a Kids Help Phone line, and tells the agent how she:

often imagined what it would be like to be dead. She closed her eyes and was floating through space, except there were no stars or planets or anything pretty, nothing but darkness. No parties with dead pets and relatives in the clouds, no coming back to life as a bird or any other animal she might like to be one day … The boredom she anticipated for the rest of eternity made her panic until she fell asleep.

The agent tells her she is cute, and Alana hangs up as her mother returns home.

These symbolic small deaths and musings on death continue into her young adulthood. In a scene from “Scraps,” a university-aged Alana sits outside to eat.

She scanned the raindrops for the albino squirrel before remembering he’d died this summer … Found hanging by his teeth from an electrical wire. She felt his absence the way she might feel for a favourite mug, reaching halfway to grab it before remembering it had broken, the pieces thrown out.

This story also alludes to the ungraspable quality of memory. In general, memory itself can have a surreal quality, the changing truth of it depending on whose memory it is, the highlights, the left out. Haldoupis not only leans into this quality in her choice of subject matter in the snapshots, but also through her prose’s poetic inclination, the language of which lends itself to sentences that leap forward, sometimes only to stop on a dime. One example of this is in “Flicker”, in which Alana struggles to be honest with her boyfriend, who clearly feels more strongly for her than she does for him.

please believe me, he said, and her screen blinked with each message, and as his blindfold slipped please believe me became you abandoned me and I needed you and I’ll always remember your kindness.

This style of writing, the running on and piling nature of it, allows the reader to make the same internal leaps that are required of them between the stories. The reader is an active participant in the world-building going on within these pages. In “Small Turtles,” the use of this craft feels almost ominous. Alana and Janie wake up in their summer cabin.

The cabin was unusually quiet, just the sound of the waves through the open window when Janie and Alana woke up to find their mother gone … She’d probably gotten caught up shopping …

To pass the time until their mother’s return, they walk to a nearby abandoned chalet where the doors have always been locked. But, “This time the door opened.” That is where the story ends. And though Haldoupis continues in the next story to describe the inside of the chalet, this stoppage creates space for the imagination of the reader to run and builds an atmosphere of uncertainty and surrealism into the very grounded details of the story.

Tiny Ruins also teems with affecting and relatable moments of social mortification, longing, missteps and romantic confusion. Alana clearly has feelings for Sara from childhood (“She wanted to be naked with Sara but knew she probably never would be and she could never tell anyone” from “Naked with Sara”) and into adulthood, but it is rarely acknowledged outside of Alana’s internal world. When Alana does speak her feelings, they are dismissed, or not acknowledged for what they are. As a child, in “Pink Jar”, she tells her mother about:

sitting on top of Sara and washing her face … Alana would use her favourite face wash, the one that smells like lemon and makes a lot of bubbles, lathering all over until it seemed like she was lathering too long.

Her mother “said it was a silly idea, that Sara probably didn’t need her help” and “Just forget about it … she can figure it out for herself.”

In “Rabbit”, Alana tells Janie about a dream she had about Sara, saying “I think I like her, that’s all.” Janie responds “It was just a dream,” and “Maybe you just wanna be like her. It’s not a crush,” and “Just stop thinking about it.” Alana thinks “maybe Janie was right.” Even within her own mind, her feelings are often dismissed. This unsaid / unfaced quality creates an almost alternate reality. It is a denial of a truth that feels destabilizing to witness from the outside. The alternative reality creates an almost disembodied experience for the reader as they attempt to inhabit the feelings and story of the character of Alana while so much of her experience of her own queerness is only witnessed unconsciously.

Alana herself attempts to deal with the alternate reality, her feelings for Sara juxtaposed with the fact that she is dating a boy whom she has little feeling for. These duelling universes are made incredibly apparent in “Dahlias”:

The dahlias on Sara’s dress scrunched and stretched with her body as she spun on the grass and Alana couldn’t understand why no one else was mesmerized.

why don’t you come over now? he said. I miss you.

Though this collection is very firmly rooted in the real, it is always gesturing to something more. Something that could be, something unsaid, between the stories, within the stoppages and continuations. The things you cannot move past until you examine them first; memory, death, love. Tiny Ruins expertly faces and turns away from these topics both through its subject matter and structure, in a way that refuses conclusivity, somehow both broad and microscopic in its focus at the same time.