USEREVIEW 038: Watch the Left Hand

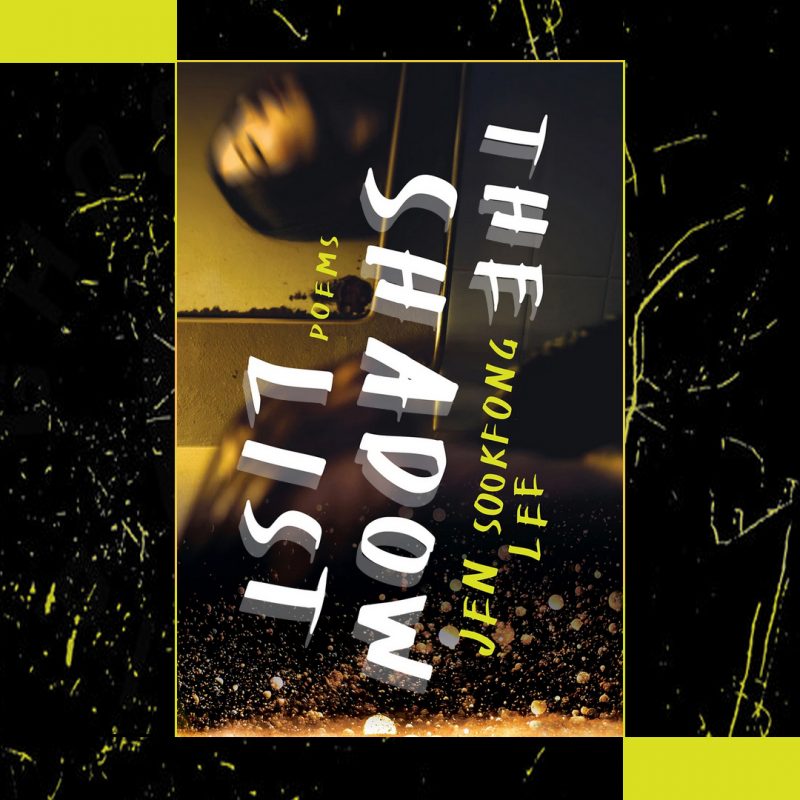

Through a process of careful and combing traditional review, Leah Bobet is able to find and extract the half-concealed magic tricks and the mixtapes from Jen Sookfong Lee’s debut poetry collection The Shadow List (Wolsak & Wynn, 2021).

ISBN 978-1-989496-28-2 | 96 pp | $18 CAD

#CAROUSELreviews

#USEREVIEWEDNESDAY

Smudged lipstick, sleepless nights and a deft structural-linguistic game that cracks binary questions of self-worth like a hatching egg: Vancouver author Jen Sookfong Lee’s The Shadow List charts a hesitating but startlingly self-possessed course through a universe of contradiction.

The internationally acclaimed novelist (The End of East, The Better Mother, The Conjoined), editor and former CBC Radio One columnist’s debut poetry collection frames a shattered narrator coming to terms with her painful divorce, a tumultuous childhood and the gap between what she wants and what she’s supposed to in tightly-knit lyric poetry, all written in a second person point of view that surreptitiously eases from dissociative to intimate. As her narrator grows, Lee shows a novelist’s structural instincts on what the narrative unit of a collection can do — and a stage magician’s on the delight of discovering not what, but how.

From a nod to how ancient Greek choruses speak a protagonist’s unspeakable thoughts in the opening piece, ‘Introduction,’ Lee’s intimate interplays between structure and narrative construct a complex puzzle-box out of what’s said, what’s hinted at and what’s seen on the page. In those opening bars — almost a poetic musical theatre overture — Lee introduces the book’s obsessions with vulnerability, decay and ambivalence about pleasure, and then uses them to segue between individual pieces and splice them together like a mixtape.

That unifying recursive tendency sets the stage for how meaningful and earned The Shadow List’s fumbling arc of character development feels: the resurfacing terror that her son “will grow up to be just like you” in ‘Introduction’ reveals its source in later-surfacing, blistering anecdotes of childhood suffering and explains why it’s repeatedly the most vulnerable nerve in a collection devoted to vulnerabilities. Likewise, repeated descriptions of the narrator’s lovers, real or imagined — a succession of men anatomized into flashbulb body parts — build into a metatextual reckoning when ‘When You Read His Poems’ probes the feeling of her own body being reduced in print to a “sliver,” a “knife.” But rather than just reproducing the crime, Lee walks up to the entire vicious cycle of repackaging other people for print with a blisteringly self-aware “Just a poem. Like this.” This iterative approach, cautiously adding context with each revisitation, accretes into a slow, crackling and increasingly absorbing look at one woman’s attempt to break her cycles.

Lee’s plainspoken, wry, direct voice and tactile, body-centric imagery support the ambitious structure by counterbalancing a funhouse of densely-packed double meanings, which never fail to provide the key to their own unraveling. ‘Introduction’ offers up: “The books are the only thing you have left / behind that make sentence-by-sentence sense,” gently handing readers the clue to deciphering a double meaning in “left” that foreshadows the collection’s later, more nuanced understandings of what’s truly been abandoned here.

That deft use of foreshadowing is parallelled on the structural level, as earlier pieces plainly chart the course later ones follow. When the poem ‘For This, You Need a Map,’ one of the collection’s notable thematic turning points, yearns to be seen and yet unseen at the same time (“Just under the surface / the waves obscure your face just so”), it explicitly provides that map for the rest of the book: how to walk that tightrope between being seen and being safe. Hidden by readers’ temporary lack of context — and yet in hindsight, clear and direct as IKEA instructions — these reflexive road maps create a delicious chance for readers to watch a magic trick: The Shadow List tells you exactly what’s going to happen and then, startlingly, it does. The rabbit comes out of the hat after all.

All this works because The Shadow List is fundamentally a work about wayfinding: between desire and duty, intentions and execution, the illusion and the props, one’s false self and the real one — if the equation is even that simple. There’s a self-awareness to itsevolving midnight disclosures that takes the inevitable uncovering of old wounds and their catharsis as only the starting point; its combination of frank disclosure and constant, spiraling, recursive, metatextual puzzles both invites and repels a psychological reading, and complicates the very urge to read it as psychoanalysis. Like any good stage magician, Lee’s left hand’s always revealing to cover what the right hand’s doing, and the constant yearning for and flinches away from intimacy don’t just describe the narrator’s relationships with lovers and her mother, but peer through the page to ask the reader to engage in a way that lets its protagonist maintain the “hard shell but fine”; lets her keep the dignity of “choking but not crying” under horrifying pressure.

While the material might theoretically invite the label of confessional, Lee’s prickly, hungry narrator avoids the assumptions around confessional poetry mostly through an immense sense of fragile dignity: one that never asks for approval or absolution. Instead, in that perpetual request for readers to meaningfully engage, Lee excavates a more profound question: how to mark the difference between disclosure and honesty? By the book’s closing pages, early pieces like ‘Rider,’ a list of self-undermining desires and chin-jutted defiance (“10. The last doughnut/croissant/cupcake because you always get yours”) are recognizable as perhaps factually true, but not necessarily honest — and the contextual truths they were avoiding become much more satisfying.

That deeper question is ultimately what makes The Shadow List such a rare, masterful read, and such rich territory for rereading. Through its obfuscations, its struggles with duality and its brittle vinyl armour, The Shadow List sets up and then wears away readerly assumptions about sex, grief and worth on a topic and in a mode that’s littered with them. And like its narrator, it ably performs the magic trick of demanding to be seen as whole, with or without full disclosures: as one complicated person being taken on her own terms.