USEREVIEW 042: Johanna Hedva’s Mad Epistemology

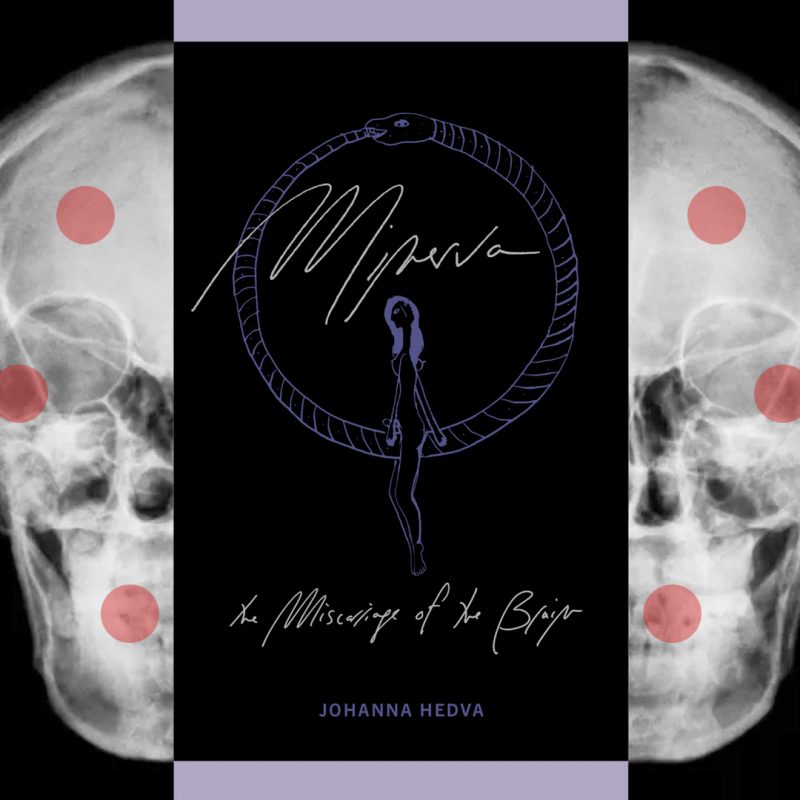

As gender and genre-bending as its subject, this experimental review by Sarah Cavar skips between theory, memoir, and experimental poetry in order to keep pace with Johanna Hedva’s hybrid literary collection, Minerva the Miscarriage of the Brain (Sming Sming Books + Wolfman Books, 2020), which “incorporates plays, performances, an encyclopedia, essays, autohagiography, hypnagogic and hypnapompic poems.”

ISBN 978-1-953189-00-4 | 194 pp | $18 USD

#CAROUSELreviews

#USEREVIEWEDNESDAY

What I needed to make this review: Twitter. My Chemex. Crystal light & valentines. The verb to slide [into (one’s) DMs].

Furthermore: Gaps. Cabins. Caverns. Holes, that is. Nighttime holes

into which I slipped tired eyes into which into Minerva A Miscarriage of the Brain into which turn into notes.

I first met Johanna Hedva in 2016, but they didn’t know it. I was seventeen, a first-month-first-semester undergraduate in an upper-division disability studies course for which only an adolescence on the internet could have prepared me. I knew I was Mad back then, but I didn’t know if it was the kind too far into my mind or too far out of it; whatever the case, it seemed the genre of wait under which I stood reflected poorly on my shoulders, rendering me / relentlessly on my hands and knees in my dreams. For class, we were required to read Hedva’s now-seminal essay, ‘Sick Woman Theory,’ whose anti-message of rest, chronicity and even failure take up (and lay down) critical tools of anticapitalist resistance, found me like ocean water. ‘Sick Woman Theory,’ explained to me the ways in which we, the Mad –– collectively referred to beneath the gender “Sick Woman,” who is a woman and unwoman at once –– constitute the weight of the all that the Well refuse to carry, all that they are too afraid to know. Madness, we see, is liberation under conditions inhospitable for sanity.

Like all genders, the Sick Woman, too, had a methodology. There was an epistemology of Madness, a fishnet web of meanings whose -ological prefixes my teenage self still struggled with, and with which I will likely struggle for the rest of my life. Yet, in Hedva’s essay, the Sick Woman’s method was and remains abundantly clear: radical care, love-as-a-verb, and rest, rest, rest.

Writer and art critic Jonathan Crary called sleep “an uncompromising interruption of the time theft from us by capitalism.” Our way of knowing is knowing (how) to bring capitalism “screeching to its much-needed, long-overdue, and motherfucking glorious halt.” That’s our dream. It is what writhes us in our sleep, our nightly resistance. A nervous condition of unrelenting rest.

In rest, I mean relentlessness, even in the face of the white supremacy, cisheteropatriarchy, and capitalism that makes us Sick Wmn. I also mean refusal, not simply as a reaction but as, itself, a way of knowing.

Minerva first rejects, then remixes, grammar, linear temporality, genre and medium. From these refusals, Hedva creates a referential buffet populated by characters including but not limited to these entries from Medea’s Shopping List:

blood & drugs 1

likes & votes 2

unsolved mysteries & blind owls 3

Sun Tzu & Rand Paul 4

peonies & sweet peas 5

taxes & greencards 6

Such unexpected pairings come interwoven with Hedva’s prose and verse, pointing toward unruly and ultimately opaque ways of knowing. They approach both the practice and the reinscription of their work through an epistemological, methodological Madness: they Know from what they see “in visions”; they create in conversation with a “stunned silence and somnambulistic madness” sometimes indecipherable by outsiders; they practice intimacy by, at one point, occupying the daily life of a total stranger as a “‘subjective participant.’” They make –– and force us, as reader-collaborators, to make also –– illogical leaps, to revel in multiplicity, literally depicting themself as a shapeshifting, plural subject. Amidst the text rest sketches of sexgender-and-species-noncompliant bodyminds, fucked-and-fucking and occasionally decapitated characters. They are all Hedva. They refuse Hedva. They are Hedva’s they, pluralized, inaugurating each successive section of a text separable yet indescre[et/te].

As such, I often find Hedva’s text slipping through my fingers. So has this review, which has been the subject of much perseveration during these last few months of on-and-off insight. I now recall that Minerva is itself, in many senses, not a book at all: it is a pastiche of performances that, in the act of pastiching, constitutes a Butlerian performance of its own. Its bookiness lies only in its continued circulation as such, a project constantly stymied by its resistance to textual confinement.

7 Minerva is 8 9 refuse.

When I was young, I went several times a year to the local church’s book fair, sifting through crates of 25¢ 90’s paperback horrors and the odd religious tract, breathing musty-book until my brain hurt. The crates towered over my eight-year-old head and would undoubtedly continue to do so fourteen years later; to make matters worse, they always seemed a half-second away from toppling. My grandparents encouraged me to raid them “to my heart’s content,” and I did, filling collapsing crates of my own.

Though I did not know it then, the books unsold at the fair would later reach their final crate at the local Waste Management facility. The books, the pulpy, precarious mess of them, were arranged so unthinkingly because they were, to the Church, already trash. The fair was a delivery vehicle for institutional refuse otherwise discardable. The boxes did not contain value, but absence, even condemnation. I was picking through the trash.

Those crates, odorous and messy and mesmerizing, are what I see when I attempt to picture what Minerva looks like. It is a story in fragments stitched and hailing from numerous years and prior publications. It does not invite cohesion, falling apart, again and again, without the promise of recuperation. Expertly baring a Mad archive of knowledge pilfered from dreams and blood and the eye-crust of kittens, Hedva equally does not demand (or even suggest) the reader’s trust. Instead, they recount their crates of absence, centering annihilations of bodily autonomy (spousal abuse, forced hospitalization), mythological and historical emptinesses and, perhaps most crucially, the substance of their miscarriage, the bitter refuse of a (re)productive life rendered Sickly unsustainable. Together, we are able to lay down

narrative control

nursing instead on figures besides reality, authors against gender, and women fucking motherfucking-fantastical horses with wily penile silhouettes.

I imagine refuse (as) the content

of my heart / cloudy

in its sweetness

Minerva is a miscarriage. A refusal of duty. A stoppage of work; a foreclosure of labor. Amid the present-emptinesses scattered between performances and commentary rests recourse to the bodymind itself, tasked with reproducing conditions under which it struggles to survive. Here, too, Hedva turns to dreams, as well as to literary myth and speculative history, to make (non)sense of the embodied reality their doctor decrees: that Hedva “was unable to hold it, the thing, together / that is, [they] couldn’t carry [their child] the right way.” In their own recollection, Hedva cites their dreams of “wolves and elephant heads / [ … ] hands sprouted with tattoos / of long sentences in a language I didn’t know.”

Stitching a litany of M’s –– “moon, mother, magic,” myth and Madness –– Hedva makes space. These stories collect things unseen, as well as things purposefully, temporarily obfuscated –– after all, “for how to disappear / completely and then return, [Hedva has] had the best teachers.” They reimagine giving birth in an ancient cave, attended-to by an anonymous man to whom they speak only in “blood, tissue, dirt, and fluids.” Yet they are also a gender in the body of a mermaid, who neither lays eggs nor has “a little vagina somewhere on her green tail.” Hedva’s mermaids eat sperm, contain the sea, lay dying eggs. In this retooling, the mermaid is a beast, “but beasts are mothers too” –– mothers who refuse to carry.

I ask, after Hedva: How long have we carried our selves, our burdens, our husbands and homes, and have we found a place to set them down? Have we been made / to burden? This is a question to which there is no answer. Instead, Minerva makes one final refusal, this time to the circumstances of their own existence: they did not spring from their father’s head or their mother’s stomach, but from the twisted, attic-bound legacy of Madwomen-passed.

While a holy text, Minerva does not leave us empty or longing; instead, Hedva fills and feels us with gifts. This is a text written to be audienced, not merely to be read: I found myself reading segments aloud just to taste them, and in doing so enjoyed a rich and richly-erotic sensory experience.

In Part IV, ‘Everything is Erotic Therefore Everything is Exhausting,’ Hedva reproduces a litany of erotic objects, senses and experiences, collected via whisper and curated by hand. The resulting, two-column, alphabetized list is not merely a tour of our collective unconscious, but a script of its own. This is an erotics of alliteration, an echo of Audre (Lorde), who wrote famously of its crucial, dangerous power to facilitate “[a] deep and irreplaceable knowledge of my capacity for joy [which] comes to demand from all of my life that it be lived within the knowledge that such satisfaction is possible, and does not have to be called marriage, nor god, nor an afterlife.” The erotic is to be shared, to be felt-between. Have a taste:

Here, connection is everything, a belief perhaps only better emblematized in Minerva’s penultimate section, titled ‘Actually, it happened a moment ago.’ Hedva documents performances for spaces falsely viewed as “vacant,” sharing their body and music with cats and dogs, chickens and seagulls. They pee by a lizard and disremember with the moon. Through all of this, they invite us in, allowing human and more-than-human entities to share in erotic power –– and destabilizing the boundary between alone and accompanied, between “live show” and textual account. I read those passages aloud before I typed one word of this review, before I had even finished the book. Does that mean you are or were here with me as I make the future you will read?

Again, these questions are answerless and unanswerable. Hedva’s project lacks as methodology, paralleling their relationship to a bed-laying insomniac’s “queer intelligence.” Their ambiguous images and succinct descriptions let us know and see with neither pressure to excavate nor recover. If “books are little coffins,” then death is an opportunity for depth, and in that depth, the reclamation of empty space. Failure to Know is, indeed, its own Mad form of knowing.

Long after saying goodnight, Minerva lies.

CODA

It is my understanding that Hedva seeks a story from me.

I offer:

q-tips in the ear canal; after-dinner chocolate mints; infodumping with a kindred Crazy,

allowing an onrush of autie-erotic ecstacy to overtake you;

summer evenings, delicious and sun-tired, fresh from the shower after a day at the beach;

ice pops; the sugar that lingers at the crook of your lips;

the bitter brown at the base of my chemex;

my sleeping writertoeszzz zzzzz

1 yum

2 ew

3 yum

4 ew

5 yum

6 ew

7 what I dream when I dream of

8 what I dream when I dream of

9 sweetpoisonwordmush