USEREVIEW 089: Mute as a Riot

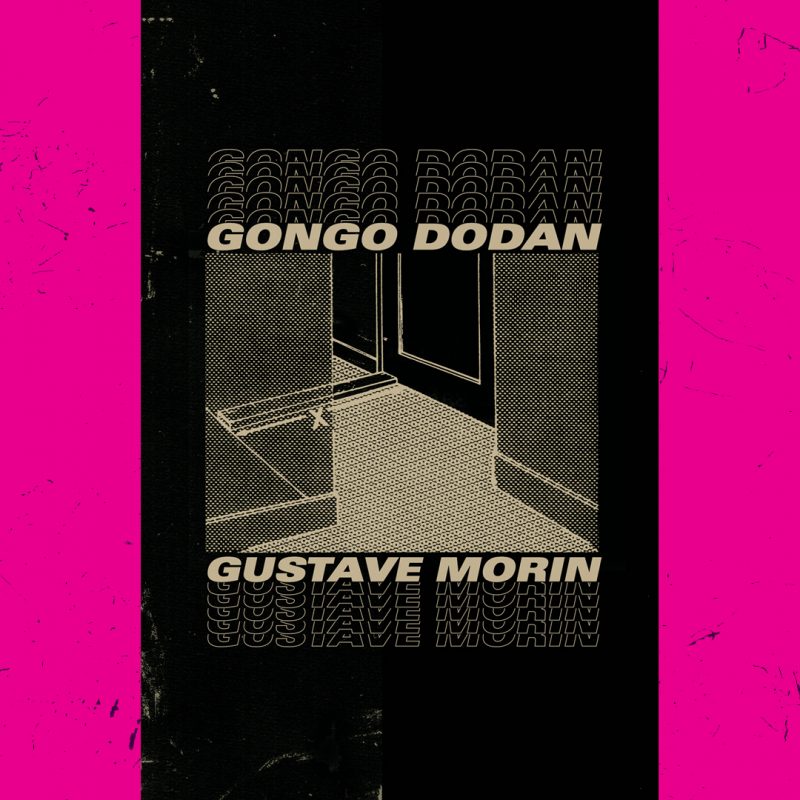

In this traditional review, Mark Laliberte offers a ouevre-spanning retrospective as context for mid-career writer Gustave Morin‘s latest poetry collection, Gongo Dodan (New Star books, 2022), the first language-forward book from this otherwise ‘visually dominant’ author.

ISBN 978-1-55420-186-0 | 88 pp | $16 CAD — BUY Here (publisher) or if you’re in Windsor, get copies at Biblioasis Bookshop

#CAROUSELreviews

#USEREVIEWEDNESDAY

After several decades of producing visually dominant ‘writing’ & releasing a constellation of projects falling into fringe literary categories like vispo, dirty concrete, narrative collage, typewriter poetry, etcetera, Windsor, ON poet Gustave Morin now delivers Gongo Dodan … what amounts to his first book of WORDS.

For those not in the know, a selection of ‘pure’ poems has been slowly accumulating in Morin’s oeuvre of works over a period of many years, written piecemeal, always a sideline to his larger vispo practice. They pop up here & there in journals, or sometimes help him to present work at traditional readings where a projector might not be made available to highlight visual poems.

Despite the categorical range, all the work he’s created to date has been clearly framed as literature, even if it hasn’t always been received as such. This new full-length collection offers an essential focal point to help refine the understanding of Morin’s poetics within the greater CanLit canon.

Still, Gongo Dodan will likely do little to dissolve Morin’s essential outsider status. Set rather aggressively in a bold serif & pleasantly detuned to the popular concerns of the moment, the 68 mostly lowercase poems presented here are littered with heroic lone wolf references, & offer up broad generalizations about humanity’s herd in a world flooded with pulsing blue television signals, squealing car tires & aging factories. Ballardian themes such as these skitter & crawl through his difficult didacticisms, which yawn out cosmically & often forsake the personal. This is a poet aware of the cold fact that our sun will burn out, yet one who can also take note of the beauty of “simple sunlight.”

Enjambment is a major structural force in Morin’s compositional field, as is language play. For example, this poetically potent short work (p. 40):

let sleeping lies

dog eat dog

biscuit

has an imagistic outer core, but also reveals a kind of bone-buried capitalist critique; not a bad feat to accomplish in seven words.

The above poetic sample also hints at a fermenting humour underlying all the various levels of cruel grief littered throughout the book. Morin seems tickled pink with clever word play & the exercise of bending proverbs or idioms to his will — as most purely evidenced by ‘half-maxims for sloppy cannibals’ (p. 28-30), a list-poem that presents 52 verbal mutations of popular, pithy phrases. Recalling poet Robin Skelton’s essential work with aphorisms, A Devious Dictionary (Cacanadadada Press, 1991), each of Morin’s lines tease at the familiar, offering condensed, often humorous slides into new language. The best of these — such as “8. where there’s a kill, there’s a fray.” or “48. the surly word gets the squirm.” — lock the reader’s mind around a thought-slogan charged with the same power that Jenny Holzer’s Truisms hum to. For those who enjoy word play, this poem will definitely be one to revisit often.

Interestingly, a third of the poems in the collection are composed using a 14-line framework ultimately suggesting the sonnet form, though they remain otherwise free verse, only occasionally dabbling with rhyme structures. There is a continual ‘othering’ of the world in the poetic voice applied here in particular, one that is almost Orwellian in its critical gaze. As a reader, I get the sense that these works (mostly presented in the latter half of the book) represent the most contemporary writings in the volume. In ‘the captain hates the sea’ (p. 65), we are invited to “stare down chaos,” aware of the dead weight of historical time, but rooted in the now, struggling,

as if each age repaid its own debt of breath

with depth of threat as another ghostly sky

swore out another complaint against runny

rivers falling behind this wrecked shipment

down the drain …

It’s virtually a cultural suicide note in a bottle, complete with a “swizzle styx” pun near its close that simultaneously evokes environmental pollution & the call of the underworld.

Lastly, we return to the book’s title, Gongo Dodan, which references a difficult-to-translate Japanese Zen kōan inadequately expressed in English as “words fail.” With this understanding, we core down to the essential dilemma that Morin probes throughout the book &, in different ways, all the way back to his earliest works as a poet: words fail. People fail; even civilizations fail. This is all here & more, squirming through the texts, filtered through the hungry eye of a carrion bird circling overhead & waiting while we all nevertheless do our best to carry on.