USEREVIEW 102: Pulsing Light

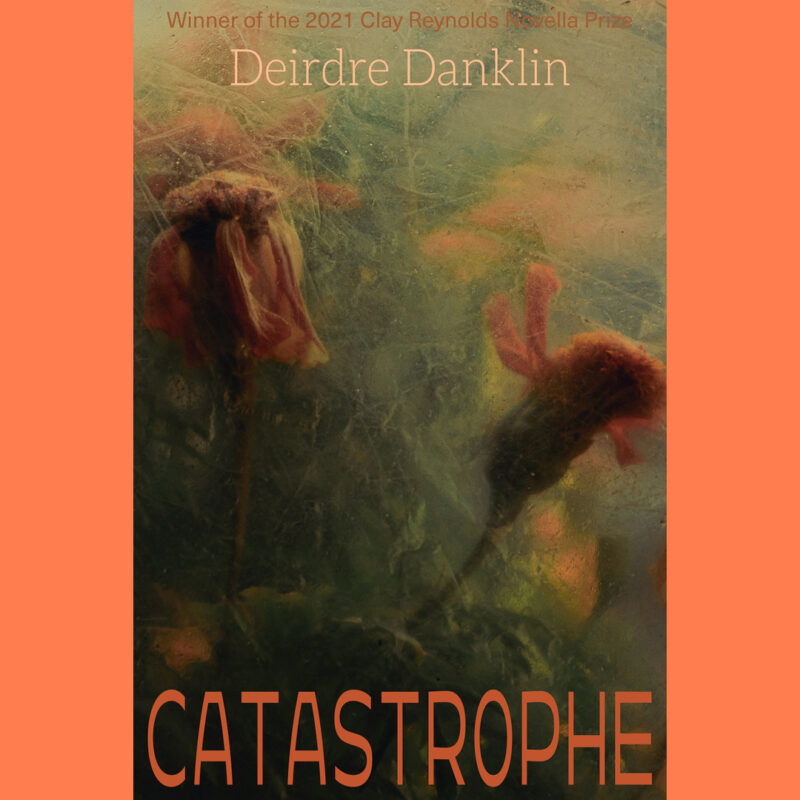

Kate Finegan finds the love and courage that bloom like flowers among ruins in this traditional review of Deirdre Danklin’s debut novella Catastrophe (Texas Review Press, 2022), winner of the 2021 Clay Reynolds Novella Prize.

ISBN 978-1-68003-273-4 | 186 pp | $19.95 USD — BUY Here

#CAROUSELreviews

#USEREVIEWEDNESDAY

In Deirdre Danklin’s debut novella, Catastrophe, two friends separated by time and distance communicate telepathically while waiting out a catastrophe that has made population centres uninhabitable. The unnamed friends established this telepathic connection in childhood, when they cut their palms with safety scissors, and their blood intermingled. One of the friends, a mother who has gone with her family to a remote cabin that belonged to her late uncle, addresses all her thoughts to her old friend but cannot hear her friend’s responses. The other friend, a woman with the power to heal by touch, is living in the desert with a dog named Dog, her closest neighbours a congregation led by a charismatic preacher who believes the congregation’s mass suicide will please God and bring the rain. The healer can hear the mother’s thoughts, and she responds with messages that are not received.

This one-way communication imbues this novella, which won the 2021 Clay Reynolds Novella Prize from the Texas Review Press, with a melancholy longing. While these women are living through a catastrophe in the seemingly near future, their imperfect connection is a timeless exploration of the enduring power — and limits — of childhood friendship. Though the adult women live far from each other and haven’t communicated by external channels in years, they’re still bonded to each other by what they went through together in girlhood. The mother characterizes the healer as “the first person who ever loved me who didn’t have to.”

Love and obligation are central to this narrative. Against the bleakness of humanity’s destruction in an unspecified, human-made catastrophe that involves drought, love shines brightly. The healer may have been the first person who loved the mother voluntarily, but the mother’s relationship with her husband is tender and open, a true friendship that provides peace in a tumultuous time.

Yet the mother must grapple with another relationship — one she doesn’t seek, which forces her to consider what we owe to strangers and to those we’re tasked with protecting. The mother becomes obsessed with the so-called “outsideman” who shows up outside the cabin and says he was a friend of her uncle’s. He sleeps in a red tent until her sister and mother drive him away. But even after he’s gone, she keeps seeing him — or thinking she sees him. When she tells him he can sleep under the porch for one night, she confides in her husband about this choice “because we have no secrets.” She’s afraid the outsideman will set the cabin on fire. Her husband hears her fears, takes them seriously and stays by her side: “We’ll stay up together. And we do. We sit on the sofa, our limbs entwined in darkness and watch the porch and wait to see if anything will make a move.”

The mother calls the outsideman a “moral conundrum.” Throughout the novella, the characters grapple with the uneasy state of being in their respective fortresses as humanity collapses. The mother takes comfort in love, but also notes that “kissing my husband tastes like blood. Loving something is living with death.”

The healer didn’t go to the desert because of the catastrophe, but she has stockpiled a ton of food. When Megan, a young woman from the congregation, shows up at her trailer, she lets her stay. In that way, she opens her safe place, her stockpiled place, to a world she does not trust, a world she characterizes as “a closed fist of people” who, in their fervour to delay the fulfillment of their suicide pact, might come for her non-perishables or her ability to heal by touch, albeit at the expense of her own health.

As this story is told through alternating internal monologues, the past is often as immediate as the present. A frequent word is “remember.” For the healer, one pervasive memory that colours every moment of her present is her toxic relationship with a woman on the coast, who likened her to a dead whale, a comparison that haunts the healer. When the healer asked what it meant, the woman responded, “Little crabs come to eat you.” In a bathroom stall, that woman has drawn a map to the healer, leading pilgrims hungry for knowledge and healing straight to her fortress. The healer believes the woman will come and take her food. The healer is particularly worried about this once she takes Megan in, just as the mother is worried about what kind of world her baby will inherit — the friends both carry the burden of care in a dangerous world.

In a novella about isolation as a means of safety, it’s delightfully ironic and achingly poignant that even the women’s thoughts are not private. They remain connected. Their shared histories resurface. They worry about each other, long after their physical connection has faded. This novella showcases the narrative power of worry, another ‘outsideman’ that can invade the most intimate stronghold — the mind. The mother describes going to a therapist before the catastrophe and cataloguing the worries that woke her up at night:

Anything. The dripping faucet in the bathroom, my baby dying, the house filling with silent carbon monoxide, my husband getting shot at work, car accidents, fires, the fact that the cicadas come out of the ground and we act like that’s normal, the things we’ll look away from, the things I close my eyes to.

Generally, the healer seems more open, more willing to look catastrophe in the face. What worries her is not so much what’s out there but what might call upon her internal gifts. She can heal with touch, but it’s so draining, it could kill her. Ultimately, Catastrophe is a story of connection, of the unbreakable bond of friendship, even after the connection has seemingly frayed. As the mother reaches to her healer friend in her mind, she’s unwittingly making her friend stronger. Just as the healer can pulse light into those who are hurt, the mother’s connection is a source of light for the healer.

Catastrophe is a highly moving elegy to what endures in the face of disasters — disasters that range from simply growing up to fleeing human-made environmental devastation. Who hears our hearts? Who gives us light? This novella shows that these gifts of human connection can endure, even if the world falls apart.