USEREVIEW 106 (Capsule): The Razor’s Edge

Karl Jirgens

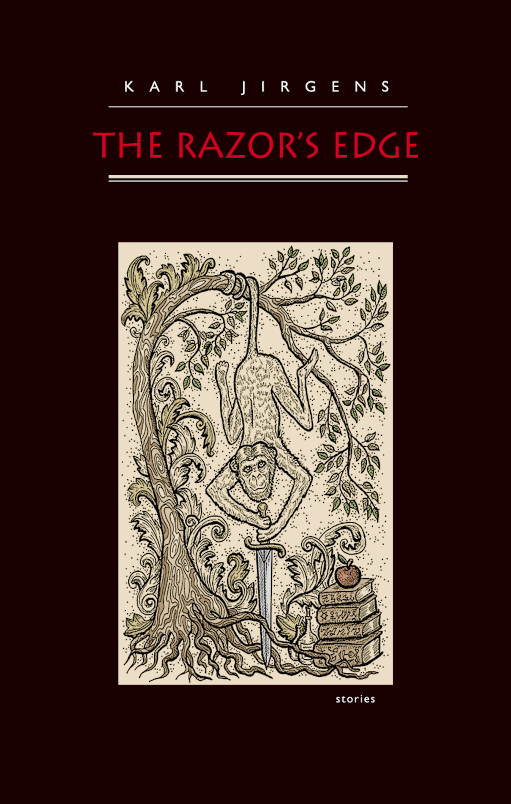

The Razor’s Edge (The Porcupine’s Quill, 2022)

ISBN | 978-0-88984-450-6 | 152 pp | $18.95 CAD | BUY Here

#CAROUSELreviews

#USEREVIEWEDNESDAY

Karl Jirgens gave me some advice years ago that I haven’t been able to forget. He said (and here I paraphrase): “If you want to be a writer, don’t become a publisher.” Whatever wisdom there might be in that aphorism, it doesn’t seem to apply very well to Jirgens himself. He was the editor and publisher of the journal Rampike (which is now archived online in its entirety) throughout its 36-year existence, from its origin in 1979 to its much-lamented end in 2016. Many literati came to know him in that capacity, possibly even more than came to know him as a long-time professor of contemporary Canadian literature and creative writing at the University of Windsor. And yet, alongside those distinguished accomplishments, Jirgens has maintained an equally impressive reputation as a writer. He’s authored fiction (like Strappado from Coach House Books, 1985, and A Measure of Time from Mercury Press, 1995), and non-fiction (like books on bill bissett and Christopher Dewdney from ECW Press). And then, in his latest collection, The Razor’s Edge, Jirgens just goes ahead and smudges out the razor-carved line in the sand between fiction and non-fiction entirely.

Though I am loath in general to speculate on whether a book constitutes autofiction, in this case one feels that Jirgens is deliberately inviting the comparison (one of his narrators is a publisher and a university professor, for instance). I might even argue that the book could serve as as a refutation of at least one poorly conceived, but now-infamous, assertion that autofiction is a newfangled concept propagated by careless youngsters. In The Razor’s Edge, the ostensibly autofictional elements seem quite deliberate and functional; for instance, they heighten the meditative significance of repetitions. Across multiple stories in the collection, the narrator(s) (who may or may not all be the same narrator), think again and again of their mother(s), who “turned cooking into an art,” in spite of, or because of, the fact that so many of her family members starved to death in work camps. Jirgens insists upon this idea, often without elaborating on it, simply placing it in new juxtapositions with other acts and memories, in a way that perhaps only someone who has done much living and writing (and even publishing) can convincingly pull off.

Recommended excerpt:

I really appreciated ‘Understanding the Sounds You Hear’ (pp. 51–65), which is strikingly odd in a way that transcends mere quirkiness. The story is narrated by a man “rereading Shakespeare and photocopying manuals for home appliances,” which he is doing, he explains, “because they will rent this place to someone else, and the new tenant will want the old manuals for the appliances I have grown to love.” Jirgens’ distinctively matter-of-fact delivery allows us to revel in the pathos, and the strangeness, of this story, without ever allowing the tale to turn maudlin.