From the Archive: Little That Can Be Done with the Pen Cannot Be Repeated with the Typewriter (CAROUSEL 36)

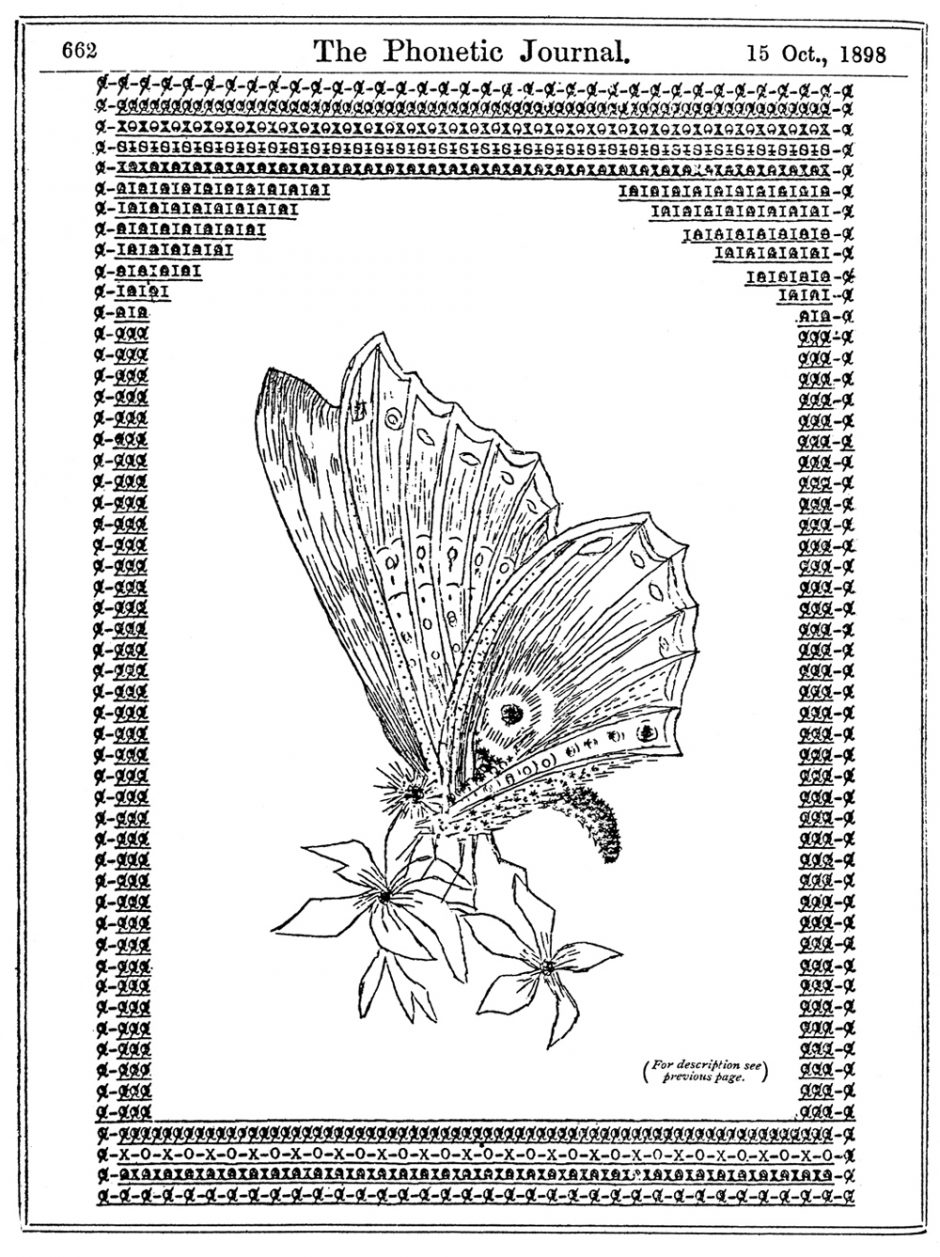

“The paper has to be turned and re-turned, and twisted in a thousand different directions, and each character and letter must strike precisely in the right spot. Often, just as some particular sketch is on the point of completion, a trifling miscalculation, or the accidental depression of the wrong key, will totally ruin it, and the whole thing has to be done over again.”

— Pitman’s Phonetic Journal, October 1898

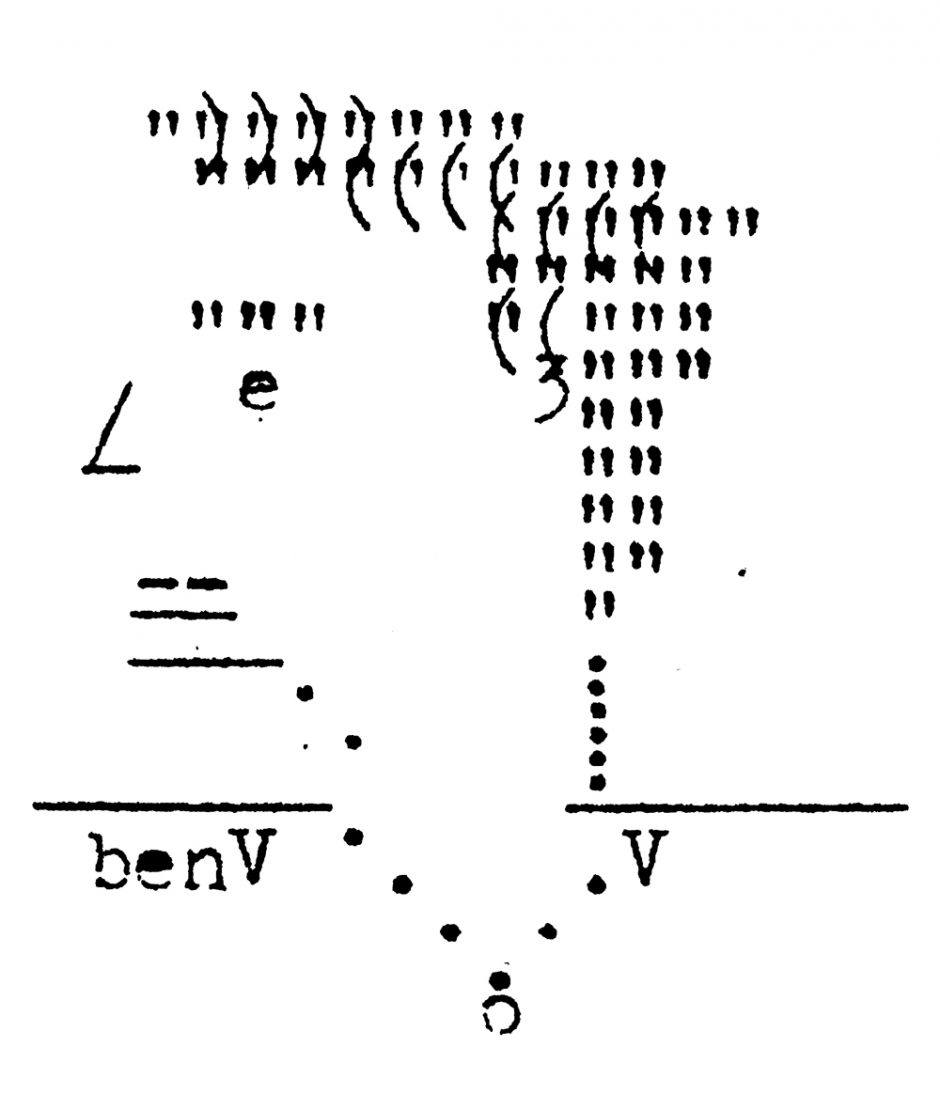

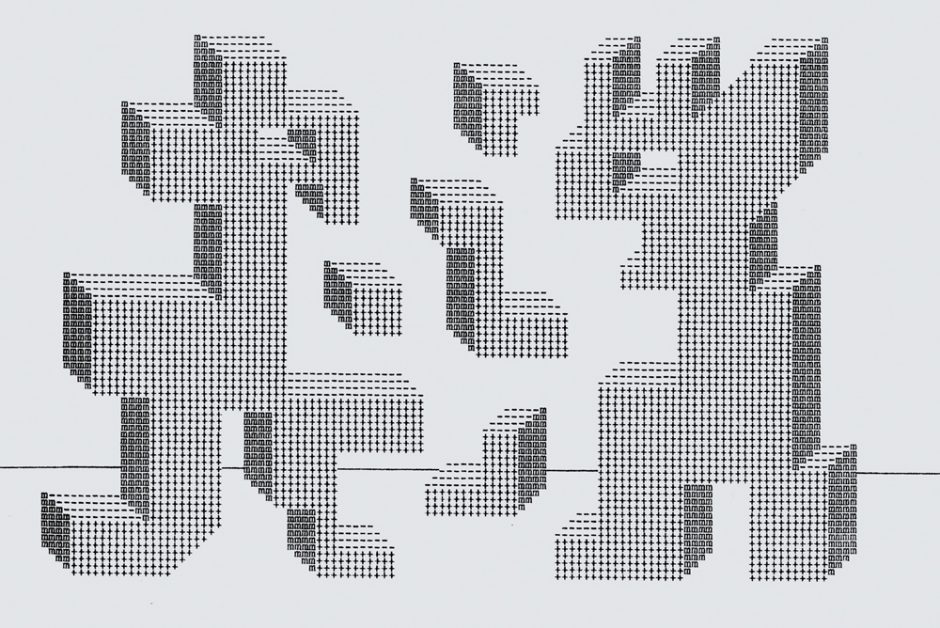

The typewriter has long signified the writer, the critic, even the intellectual, but do we think of it as a sign of the artist? Many formative works of no little effort and exceptional skill lie anonymous — barely 100 years old — as testimony to the simple beginnings and silent evolution of typewriter art. The typewriter, once an essential tool for formal communication, was quickly reduced by rush of progress and invention to a novelty item, decorative piece and even — as with so many casualties of the digital age — an affectation. Such regression has mapped a gradual loss of function, so how to consider and qualify the significant body of typewriter art created over the last 125 years? How also to nurture the future of a medium that has managed, for the most part, to thrive in comfortable obscurity?

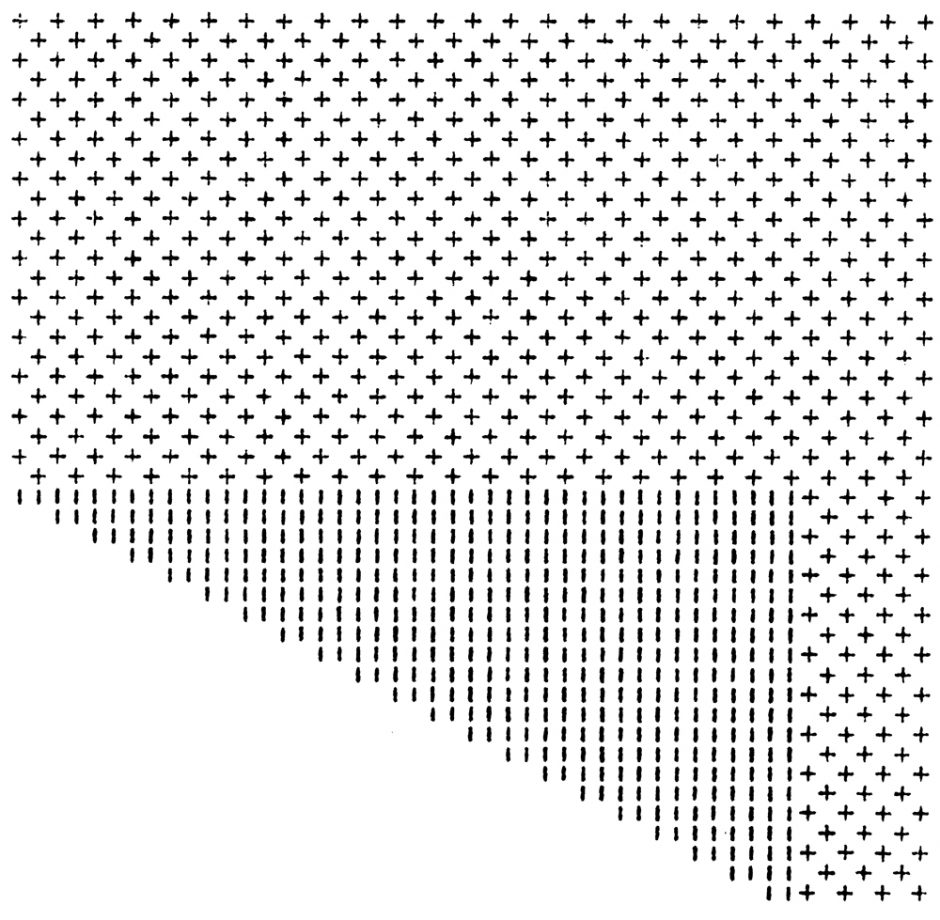

Produced by Remington, the first successful commercial typewriter was made available to the public in 1874. Much like the smart phone the typewriter steered social, cultural and commercial discourse in directions previously unimagined. It placed mass communication in the hands of the individual and was instrumental in female emancipation by ushering women into the workplace. While the word ‘secretary’ may have devolved into a twenty-first century slur, secretarial schools of the 1890s represented a hive of activity in the stirrings of typewriter art. Early attempts to surpass the typewriter’s mono-functionality promoted its potential to embellish with type as stenographers and students were encouraged to submit original pieces for public consumption and competition in popular publications like The Stenographer’s Journal. Flora F. Stacey’s Butterfly (1898) is oft-credited as the oldest surviving record of typewriter art; the surprising effectiveness of what is no more than a collection of dashes and brackets still towers as the most recognizable piece from what is arguably the most enduring figurehead of ‘art-typing’s’ infancy.

Much of 20th century typewriter art exists in private collections, long obscure first prints or limited editions yet we can still piece the story together. In TYPEWRITER ART: A Modern Anthology (Laurence King, 2014), graphic design scholar Barrie Tullett provides a detailed yet fascinating record of the history and trajectory of typewriter art by following the instrument itself as a medium for creating works far beyond anything envisioned at its conception. From the earliest published pieces (Mrs. Arthur J. Barnes’ How to Become Expert in Typewriting, 1890) to Stacey’s Butterfly and on through Keisler, Pietro Saga & De Stijl in the 20s, the concrete poets of the 50s and 60s, Paul Smith’s triumphs over physical disability, the towering contributions of Henri Chopin, Dom Sylvester Houedard, and bpNichol, Alan Ridell’s curated exhibitions and Typewriter Art anthology in the early 70s, Steve McCaffery’s seemingly never-ending Carnival and on to contemporary experiments in texture multi-layering print-scan and copy, Tullett posits the definition of typewriter art to be both broad and intensely personal, “for some artists it is an object to draw — from the machine itself to the ephemera associated with it (typewriter oils, ribbon cases and so on) — or an object to make art from, however, the typewriter is a tool to draw with; a means of making art”. Tullett hypothesizes that the personal computer has resurrected the history of typewriter art by re-animating its back catalogue and driving a new generation of artists to achieve disarming results with ‘obsolete’ equipment. A particular strength of Tullett’s anthology is the time afforded to contemporary artists such as Allyson Strafella, Leslie Nichols and Keira Rathbone, who create staggering pieces through innovation, ‘live action’ and a willingness to embrace tradition.

The Art of Typewriting (Thames & Hudson, 2015) by Marvin and Ruth Sackner lovingly mines the Sackner Archive (probably the largest collection of visual and concrete poetry in the world; founded in 1979). The Sackners were drawn to purchase artworks, trade editions and unique books that integrate word and image, as well as those that depict experimental typography. Both the Sackner Archive and this representative book were birthed by a fortuitous find on a dusty top shelf in a New York book store where Sackner unearthed Emmet Williams’ Anthology of Concrete Poetry (1967) and went on to purchase the shelf’s contents in full. The Art of Typewriting devotes significant space to representative works of the most important concrete poets and typographic artists and less to tracing a line of hypothesis through the history and trajectory of typewriter art. The Sackner book is a fine collection that uses text sparingly as means of context and introduction; for the most part its content is devoted to plates and reproductions that serve as both excellent introduction and fertile foundation in the best that visual and concrete poetry has to offer. Each and every copy of the 352 page hardcover book, designed by London’s Graphic Thought Facility, boasts a unique combination of typewriter art on its front and back covers — a clever use of contemporary print technology, achieved through a custom algorithm which processes data fed through a digital press.

In recent years it is noticeable how contemporary projects like Nadine Faye James’ Typewritten Portraits revisit the playfulness suggested on instructional sheets that accompanied the earliest machines. Never completely forgotten, many artists are rediscovering analogue/mechanical techniques because they want to experience the tactility and physicality of making art ‘off screen’. In the age of the home computer, fonts and laser printers are consistent and mostly silent, but the old typing ‘voice’ gives the artist a sonic rhythm to respond to. Heard in the aural impact of creation, this is a voice which can alter and surprise within a piece that might otherwise retain elements of control and premeditation. From nostalgia and curiosity to a resurgent popularity typewriter art persists by nature of its innate unpredictability and the endless possibilities that confers.

“Perhaps there is a wonderful insanity in the desire of so many people to make such a great range of art from such a stubbornly uncompromising machine. If so, long may the typewriter keep inspiring us to make such madness.”

— Mark Twain

Little That Can Be Done with the Pen Cannot Be Repeated with the Typewriter appeared in CAROUSEL 36 (2016) — buy it here