USEREVIEW 050: Curating Vulnerability

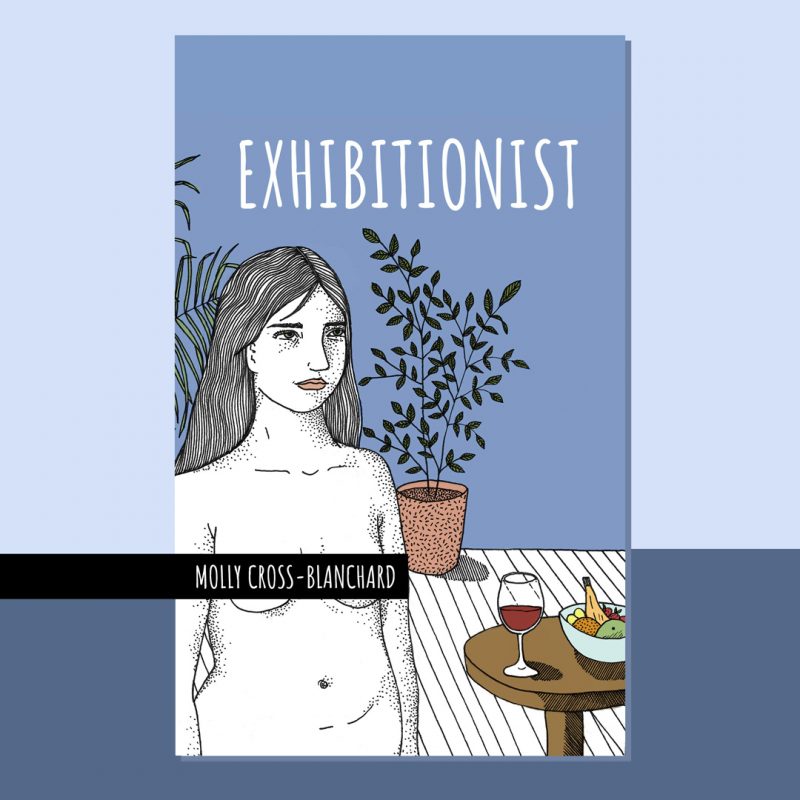

With a conversational and knowing tone, Joelle Kidd uses the medium of the traditional review to reveal the layers of complexity on display in Molly Cross-Blanchard’s rollicking debut poetry collection, Exhibitionist (Coach House Books, 2021).

ISBN 978-1-55245-422-0 | 112 pp | $21.95 CAD — BUY Here

#CAROUSELreviews

#USEREVIEWEDNESDAY

“They will call this vulnerable,” the speaker of Exhibitionist declares, “because it’s a book written by a woman / and it checks the woman’s book vibes: / Heartbreak? Check. / Ghost children? Check. / Yearning? Checkeroony, baby.”

This, the opening of the book’s final poem, reflects the collection that came before it: self-aware, referential, playfully poignant and gleefully crude. Molly Cross-Blanchard’s debut full-length poetry collection toys with this notion of female vulnerability, turning concepts like nakedness, exposure and shame over to examine them from all angles.

As Cross-Blanchard — who told feminist literary magazine Canthius in an interview, “I won’t even attempt to refer to a ‘speaker’ because she is me, I am her, and that’s the whole point, really” — slyly points out, women’s art is often described as, or presumed to be, vulnerable, revealing. A woman who writes is often praised in terms of her bravery or boldness in her willingness to expose herself — it’s almost required to offer up some kind of weakness, some pain.

Yet to expose yourself is to end up exposed. And those who show too much may end up subject to scrutiny, shamed for their exhibitionism, for the revelation of their supposedly unseemly parts. “I want to be more / Like the woman in Burger King / who eats fries straight off the floor, / the woman who cries in Walmart,” Cross-Blanchard declares. In a collection of poetry dedicated to “the young people who feel so embarrassed, all the time,” she embraces, even chases after, shamelessness.

Many of the poems circle around youth and maturity, chronicling drunken nights, insecurities and first experiences of adulthood. Several poems explicitly compare the speaker’s perception of herself to others, at different ages. “I’m twenty-five / and smelling the crotch of all my jeans,” she writes; “I’m twenty-five, in a basement suite with rats / that scratch in the walls at night.” Elsewhere, “Billie Eilish / is seventeen. When I was seventeen I was so worried / about the hem of my Giant Tiger jeans.”

Often childhood is juxtaposed with adult sexuality — “I jerked off […] between my cousin’s PAW Patrol sheets”; “The best sex I ever had was on a Disney vacation”; “The most orgasms I ever had in one go / came over Christmas vacation / in my childhood basement bedroom”. This has the effect of heightening the absurdity of sex itself, and of the way we tend to compartmentalize the sexual from other parts of life. Cross-Blanchard resists these boundaries, often with relish. In ‘I go to the orthodontist,’ the speaker gets her permanent retainer removed in order to “give better blowies” — “I’d rather be a gap-tooth bitch than a peen paper shredder” she neatly summarizes.

Lines like this can rip a laugh out of a reader, deftly melding poetic form with the colloquial, and the cadence of online speech. Cross-Blanchard has perfect pitch for the conveyance of modern life, her imagery tracing the textures of our semi-virtual reality — “invade my inbox, subject i’m sorry” — and style capitalizing on the syntax of online communication. “I keep FaceTiming my friends / so I can cry (I didn’t come up with that myself) / ((everyone on Twitter is smarter than me)).”

Formally, the poems are colloquial and flowing, as gulp-able as cheap wine bought for a night in. The collection is varied in its rhythms and subject matter, each poem working out its own emotional beat. Cross-Blanchard’s language feels musical, and favourite words and phrases echo through the pages like leitmotifs — the deep throb of “your thumb,” “thumb-toed”, “two fat thumbs”; the sing-song plosive of “baby,” “ghost baby”; the slinky pleasure of “pussy”; the almost snide fricative anchoring “Netflix.”

Cross-Blanchard also explores her Métis heritage in several poems. The tender ‘Pinky drum’ takes the form of a message from the speaker’s mother. ‘First-Time Smudge’ also wrestles with the complexity of racial identity and family as the speaker melds traditional knowledge and the Google search bar. In continuing self-referential fashion, ‘We’ve all got a poem called Blood Quantum’ muses on the different ways identity can be imposed or categorized. “I don’t wanna have to tell my babies You’re Métis, / but Can*da says you can’t have the card,” she writes.

Babies, always theoretical, always in the future tense, appear again and again. The hope of motherhood carries throughout, often laid symbolically over other hopes: of a healthy, fulfilling romantic relationship, a secure and stable future, a dream of future perfection (“When I’m older / I’ll be so good at giving birth,” she imagines). Motherhood also stands in for anxieties about career and artistic success, and the marginalization of mothers who are artists — “The baby / will infect the poems and the resulting book will go largely / unnoticed, but oh well.”

Cross-Blanchard particularly revels in, for lack of a better term, the gross. Piss, shit, body hair, menstrual blood, pocket lint, earwax — nothing is off limits. “I’m a woman without a lover / so I dutch-oven my dog on the daily,” one poem begins. In another the speaker confesses to once running out of toilet paper and using “a torn-off piece of tampon box”; in another she masturbates while driving and rinses her “pussy fingers / in the last sip of gas station coffee at the bottom of the styrofoam cup.” At times the grossness of having a body is juxtaposed against the ideals of femininity and adulthood, associated with the vague sense of shame foisted on women who might be perceived as a “mess”. The “messy woman” is a powerful cultural figure these days, having crashed our screens in shows like Broad City and Fleabag (the speaker has to remind herself she’s not Phoebe Waller-Bridge after watching the show). More than ever before, women have space in art to portray the unpolished, to push back against narrow definitions of femininity. Yet the problem Cross-Blanchard refers to in her invocation of “women’s fiction” still exists. For a man, employing earthy humour, self-deprecation, or a warts-and-all approach becomes only a part of their signature style; for a woman it becomes part of a trend, a trope. It gets figured as “vulnerable” or radically honest; it comes to represent something about womanhood in general.

In one poem, ‘I famously don’t care / about germs,’ the gendered tension surrounding grossness is explored through the speaker’s memory from eighth grade of dunking her head in a puddle of dirty water on a dare. “When I come up for air and my dirty hair sops all over my shirt / he’s watching Jessi,” another girl. “I don’t even care,” the speaker says, unconvincingly. The male gaze undervalues the daring nature of venturing into the gross, or else views it as a curiosity. But it refuses to hold it in tandem with a feminine sexuality, just as the speaker’s youthful attempt to impress disqualified her as an object of romantic desire. Cross-Blanchard refuses to toe the line of this dichotomy.

This theme is echoed in the poem ‘Dear Mr. Decker.’ The speaker tells the story of the boys in her second grade class threatening to hurt one of the girls unless the others would show them their panties.

I was the first to lift my skirt. One was always good enough for them.

They’d let the small girl go and she’d wipe snot off her face and pretend

none of it bothered her very much, and we’d all go play marbles in the

shale together as if nothing out of the ordinary had happened.

When the boys demand the girls’ bodies be put on display, the speaker here is the first to step forward — an act of bravery, surely, as well as a capitulation. Vulnerability is a shifting target, perhaps, one that depends as much on the audience as the exhibitionist to define. “Is it vulnerable / to write I love my massive rack or is it / just a fact?” the speaker asks. There is a trick to revealing, as it requires curating one’s own vulnerability for the audience; Cross-Blanchard is an exhibitionist in both senses of the word.

Nakedness is an elastic metaphor. To be naked may be to be embarrassed or empowered; it may signify innocence or knowingness; it is to be stripped bare or to be natural and whole; sexual or infantile. Exhibitionist takes on all of the above. Checkerooney, baby. Cross-Blanchard bares all — only showing, of course, what she wants us to see.