USEREVIEW 062: A Bloodstory

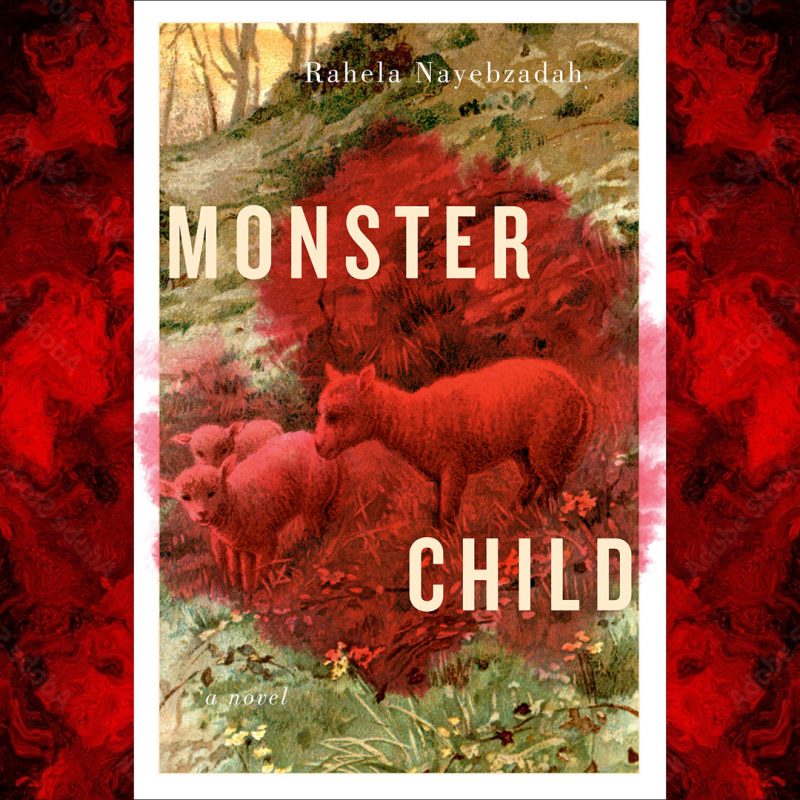

Emily Woodworth’s exquisitely lyrical review of Rahela Nayebzadah’s debut novel, Monster Child (Wolsak & Wynn, 2021), is as urgent and visceral as if it were written in red ink.

ISBN 978-1-989496-30-5 | 200 pp | $20 CAD — BUY Here

#CAROUSELreviews

#USEREVIEWEDNESDAY

Blood flows through Monster Child by Rahela Nayebzadah until it animates, breathes, becomes a body in your hands. Then three bodies. Then six. A disease festers in the pages. Bloodguilt spatters the lives of three children as their blood ties or lack thereof ooze into every crevice of the narrative to form a mosaic of their lives. Though a slim volume and a relatively quick read, Monster Child is certainly not light in its subject matter. Its great strength is in Nayebzadah’s ability to control the ambiguity and nuance that flourish in these pages.

Epic romance, dire straights and desperate flight form the historical background before which a family drama plays out. The narrative follows three adolescent siblings during the spring of 2000, during which Afghanistan under Soviet rule colours their parents’ memories, while the sibling narrators, raised in Canada, navigate blood — both literal (the novel begins with a trip to a farm where animals are slaughtered according to Islamic methods) and figurative (as in: bloodlines, heritage, and so on) — and racism. Their experiences pose (and leave unanswered) the question: how does one survive difference in a place that doesn’t tolerate difference? This holds true within the domestic space, as much as in the public (white) one, making for a dynamic exploration of second-generation immigrant experiences.

The siblings’ stories are told in

parallel lines, not crossing

in the text, but date-stamped to show overlaps and

interstices, gaps, as if to say . . .

We all live life in parallel. We all live life in parallel. We all live life in parallel.

The first child, Beh, youngest sibling of the three at just thirteen sees blood, bleeds and suffers violence. Her thread is shadowed by a sexual assault early in the novel, as she wrestles over how and when to disclose this attack. She is defined as a disease by her family as she persistently disrupts the status quo, both in her public sphere at school, where she infamously and very publicly confesses her love for her English teacher, and in the domestic space, where she chafes against tradition and speaks her mind. Her brash attitude and confidence in her poetry are a winning combination, and, as she points out, her disease nature “grows” on people (and readers). Assaulted during her section in Monster Child, she holds pain close until it turns into bloodlust, and uses her literal blood to strike back at her attacker. “Monster, monster. I am a monster,” she thinks to herself, a refrain that compellingly stitches the book together across the otherwise wildly different sections.

The second child, Shabnam, the oldest of the three, cries blood, bathes in blood and spews it, when necessary, from her eyes across a room. This ability could easily become a predominant narrative force in the book — a speculative element that would become the main plot point in a lesser writer’s hands — but Nayebzadah does not let the existence of these bloody tears dominate Shabnam’s personality, or take undue attention away from the issues she wishes to investigate. Her characters see this ability as just another difference they must obscure from view. Instead of becoming her main character trait, Shabnam’s bloody tears function as a way to inform her inner struggle: as the daughter of Padar (father), but not of Mâdar (mother), she holds only one bloodline to a living parent, her own biological mâdar having died when she was young. Her ocular excretions mark her as different from her siblings. Her tears may fill bathtubs many times over (quite literally), but it is her need for knowledge of a blood mother that makes her feel monstrous. Her disowning of the mâdar who raised her makes her think to herself, “Monster, monster. I am a monster.”

The third child, Alif, second-born and only son, is bloodless, unmoored from his own assumed heritage, though he doesn’t know it yet. As the only son, he sees more than the others, witnesses bloodshed but doesn’t speak; knows what to do, but does not act. Alif stands complicit in violence against Mâdar, and displays most prominently the dilemma of choosing to keep silent to insulate his family, or to instead navigate a racist legal system. As he watches his family falling apart, and delays taking action, he sees in himself his father, and thinks, “Monster, monster. I am a monster.”

More bodies shadow these three. Padar and Mâdar and Padar’s first (late) wife form a triangle of power, love and hate that flows through Monster Child. In Shabnam, Mâdar faces each day the spectre of her husband’s late wife, and clear “first love.” She works throughout the novel to dutifully overcome his obvious, lingering passion for her, while navigating her relationship to Shabnam. Meanwhile, Padar attempts to give Shabnam a connection to her biological mother, releasing details about her, even purchasing a bird at Shabnam’s request, bringing this past wife symbolically into their current home. Ultimately, the story of the children is the story of their parents, and the revelation of the parents’ “love story” (or “lack of love” story) forms a heart at the centre of this family saga that otherwise might have felt disjointed. As losses accrue, and more lives are lost (you’ll have to read the book to discover whose) a ghostly apparition forms — a soul of sorts — crossing the narratives and making the book live. What appears a simple structure on the surface — three parallel stories — becomes a complex and layered portrait of two people struggling to remain together, to forget the past while the faces of their three children can only remind them of it constantly.

By the end, the children’s own self-admitted monstrosity serves to protect them from what is shown to be a monstrous world. As in life, their monstrosity is marvellous, humorous and hurtful by turns. There is joy in this book, for all its weight, and those moments help keep the reader invested. And always, the joy is complicated by family strife and pain. As Shabnam and her father happily sing a touching father-daughter song to each other in one of the light moments, it serves to throw into high relief for the reader Beh’s place in the family system. This highlights one of the most accomplished elements of Nayebzadah’s debut: the opacity of the characters to each other. Each child inhabits their own monstrosity and jealousy at the small moments of reprieve each experiences, unaware that their siblings are in the same predicament. Yet when the three join together, they are capable of destroying a little part of the monstrous world around them. Alif’s narrative ends the novel by bringing the three of them together to finally fight a common enemy within their extended family. Though his final thoughts are not optimistic, the book’s ending is not devoid of hope either as we watch the siblings find commonality and strength, together.

As with many family dramas, this one follows the lines of a tragedy. Yet in Monster Child, Nayebzadah has struck a careful balance between bloodletting and bloodbath. With vividly drawn characters, richly explored culture and precise renderings of the spaces these characters inhabit — both internal and external — Monster Child breathes.

When you close the covers, you will find yourself holding a beating heart: your own.