USEREVIEW 071: Looking for Lost Keys

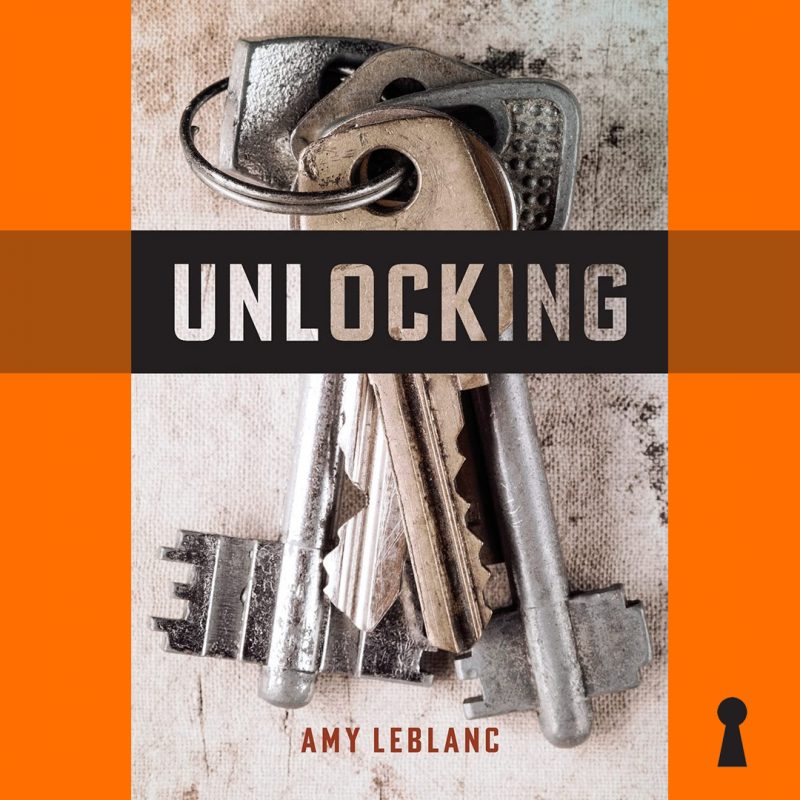

Kate Finegan throws open the doors and windows to inspect the architecture of Amy LeBlanc’s debut novella Unlocking (University of Calgary Press, 2021) in this traditional review.

ISBN 978-1-77385-139-6 | 112 pp | $19.99 CAD/USD — BUY Here

#CAROUSELreviews

#USEREVIEWEDNESDAY

In a 2020 interview with David Ly for PRISM International, author and poet Amy LeBlanc discusses the impact of fairy tales on her work: “When I read the Grimm’s fairy tales for the first time and discovered that they were much darker than the Disney versions, I fell even more in love. They contain all of my favourite elements and motifs: ghosts, haunted houses, poisonous plants, witches, and so much more.”

LeBlanc’s debut novella, Unlocking (University of Calgary Press, 2021) showcases this influence but grounds it in the reality of a small town in Alberta where everyone knows — or thinks they know — everyone else’s business. At the novella’s centre is Louise (Lou) Till, who has inherited her parents’ hardware store after their shocking death by carbon monoxide poisoning. In their absence, her marriage has dissolved, and she is living at the hardware store, unbeknownst to her employee and her customers. Also unbeknownst to anyone is her troubling habit of keeping copies of the townspeople’s keys for herself.

Unbeknownst, that is, until New Year’s Eve, when Lou lets herself into her old neighbour Euphemia’s house to retrieve a toolkit she had loaned out. Euphemia’s house is filled with poisonous plants, and in her prologue, she confesses having supplied a local woman with polypore pieces that could cause kidney failure after some teenagers slandered the woman with graffiti calling her a slut. Euphemia occupies the archetype of a witch as an older woman, often considered “batty,” who makes things happen. She also views the town from a detached vantage, doling out wisdom such as “the earth of this town is ripe with whispers and furtive conversations” and “a goldfish will eventually grow to fit the size of its bowl, and the same is true of secrets.”

She is the one who ultimately entangles Lou in a life of crime. When Lou enters Euphemia’s house, she notices that Euphemia is barely breathing. In the hospital following the 911 call, Lou learns that Euphemia has been asking for her in her lucid moments. She confronts Lou with a simple statement: “You broke into my house.” She agrees not to tell anyone about Lou’s key-hoarding if Lou will help her get to the bottom of a mystery. Euphemia is convinced her best friend, Isabella, whose recent death was attributed to natural causes, was actually murdered. She believes the proof lies in a necklace that Isabella never took off but was not wearing when she was found dead. She believes the killer did the deed then ripped the necklace off. Her plan is to have Lou let herself into the homes of suspects around town to search for the necklace.

In the aforementioned 2020 interview with Ly, LeBlanc goes on to say, “The poems in my collection, I Know Something You Don’t Know, were definitely influenced by fairy tales, but folklore, historical narratives, and individual experience are also influences.” The same is true of Unlocking. The narrative includes a wide array of allusions to nature-focused folklore, like the belief that bees must be informed of important events or their honey will dry up, and the poetry of keys, imbuing their very architecture with an almost mythical quality through the power of attention. As Euphemia says, “A key’s valley, shoulder, code, and other features make up the small piece of metal we use for security. A sense of security, anyway.”

Stories separate characters and bring them together. Lou’s employee, Cass, goes her whole first day at the hardware store without speaking to Lou. Instead, she keeps her headphones on and listens to a podcast about the dancing plague of 1518, in which inhabitants of a small town could not stop dancing; she reports, “a lot of them danced themselves to death.” Again, poison shows up in the true facts of this historical retelling: “They thought people had been bitten by poisonous spiders, but it was just flour that had gone fungal, and they were all having seizures.” Lou responds that Euphemia is a repository of similar stories and that Cass should ask her about the Great Kentucky Meat Shower.

You may be thinking, “But what about the murder mystery? How do folklore and historical anomalies inform the whodunit?” That is the question that I find myself grappling with in writing about this novella. The central mystery is ostensibly “Who killed Isabella?” yet this storyline is less complex and rewarding than the atmosphere which surrounds it. Lou enters homes, often unwillingly, but also with an unexpected thrill at getting away with this crime. To solve a crime, she enacts a crime, over and over. She makes frequent careless mistakes, breaking a vase or forgetting to lock the door behind her. While everyone in the town seems to know everyone’s business, no one suspects the woman who cuts keys for everyone in town. In a novella exploring the complexity of grief, secrets and the unknowability of others as well as ourselves, the movements of the mystery are oversimplified. This includes the resolution, in which a clear smoking gun is forgiven due to a convenient agreement which is at odds with the gravity of the alleged crime, the murder of Euphemia’s dearest friend.

The murder mystery at the centre at the novella is perhaps the occasion for the telling, but it is not what ultimately held my attention. Rather, the central arc may very well be all the incidentals— the stories, the seemingly random facts — that accrue through the fits-and-starts attempts to reconnect with community after an unimaginable loss. Perhaps living through grief is like unlocking neighbours’ doors and rifling through their experiences to find some sense of connection or peace. Ultimately, what Lou gets from Euphemia is the assurance that her parents had been happy, that it was a coincidence that their car was left running in the garage while the carbon monoxide detector was unplugged. By the time this revelation happens, however, the narrative has veered so far from the question of Lou’s grief and guilt over her parents’ supposed suicide that the impact is dulled.

In a recent Read Alberta interview with Uche Umezurike, LeBlanc explains the grief within the novella as follows: “I didn’t initially set out to write a book about grief, but the further I got into writing and drafting, the more I realized that the experience of grief was the thread that twisted through the entirety of Unlocking. Lou is grieving the loss of her parents and her nuclear family unit. Euphemia is grieving the loss of Isabella. Neighbours are living through all kinds of experiences no one could have guessed. Through their combined grief, I found that I could write layers into these characters that I hadn’t expected.”

Indeed, grief twists through the pages like a key. But like a key, sometimes it gets lost.