USEREVIEW 115: The Can’t-Miss Poetry Catch-Up

As a Reviews Editor, I try to be conscientious about only ordering ARCs that are likely to actually get reviewed for CAROUSEL. Publishers, especially small presses, often run on tight budgets, and I don’t want them to spend time and money sending out books that will languish on a shelf.

But I’m also only human, and sometimes I miscalculate, and we end up with more books than review slots, or a book I would have loved to see reviewed gets sidelined for a book one of our reviewers is really excited about.

Over the past couple of years, CAROUSEL has accumulated a small stock of ARCs that haven’t yet made it into USEREVIEW. I was going through this stock the other day, and realized there were actually several books in there I had gone so far as to read, I just hadn’t had an opportunity yet to give them a review.

This is hardly a dire problem, and yet it nags at me periodically when I’m trying to sleep at night. There is a tendency in publishing, and consequently in reviewing, to be forever pushing toward the next, newest set of titles. More books than ever come out every year, and so many of them are good, that it’s easy for books to get passed over even if they’re eminently deserving of attention. We generally try to keep things current at USEREVIEW, but occasionally I want to push back against the fast-moving publishing and reviewing cycle.

Our 2023 is already pretty tightly packed with a ton of exciting new work coming out this year, thanks to the expansion of our Reviewer-in-Residence program, but we do have a few open weeks left, and I want to take this week to revisit several exceptional poetry collections I read over the course of 2022.

#USEREVIEWEDNESDAY

2022

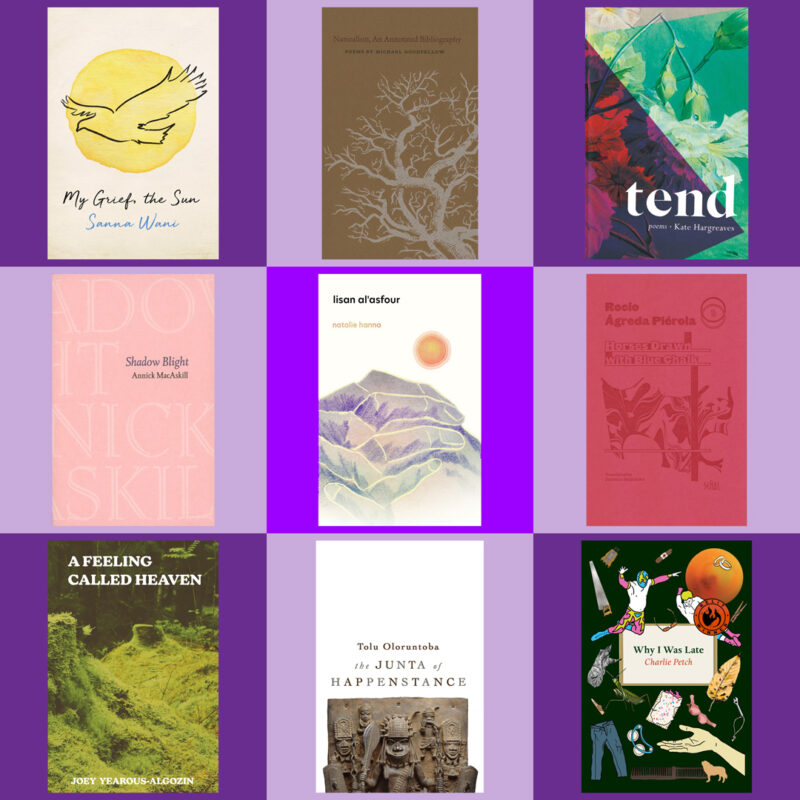

I had been looking forward to Sanna Wani‘s debut poetry collection My Grief, the Sun (House of Anansi Press, 2022) since I read her 2019 chapbook The Pink of the Seams (Penrose Press), and the book did not disappoint. Wani has evidently both expanded and refined her poetic craft in the intervening years. Slipping gracefully between subjects as disparate as pop culture and theology, while maintaining her recognizably disarming mix of poignancy and sweetness, Wani’s formal approaches in My Grief, the Sun are likewise varied. The collection incorporates elements of visual poetry (“Dorsal”), prose poetry (“Schizotheism”), suites (“morphology”), epigraphs (from M. NourbeSe Philip, Rabia of Basra, Alex Dimitrov and more), annotations (definitions, primarily), creative sectioning (the fourth section “Distance” is subsectioned into successive seasons) and other devices. This eclecticism does give the book the feel of a debut collection, of a poet testing the breath of her considerable powers, but it also makes the text hard to look away from, with surprise after surprise appearing on each successive page.

Like its press fellows, Michael Goodfellow‘s debut poetry collection Naturalism, an Annotated Bibliography (2022) carries the unmistakable design characteristics of many a Gaspereau Press book: a cover stock jacket featuring an image from an original wood engraving, a dark offset-printed cover with metallic ink, high-quality Zephyr Antique Laid paper on the interior pages and impeccable typesetting. That attention to detail in the printing of the book is well-emulated by the content of the work within. Goodfellow writes with precision and a keen eye for both the touching and the unsettling details of daily life in rural Nova Scotia. His is a world where a ‘saw’ or “a tin of oats” is as integrated into the landscape as a ‘hummingbird’ or “berries on the winter holly.” Resisting the bucolic, these poems bring forth the liminal, the sensual and the macabre inherent in the mundane tasks and scenes of human existence.

Kate Hargreaves‘ sophomore poetry collection tend (Book*hug Press, 2022) is a long-anticipated follow-up book that builds on the work she accomplished in her debut collection leak (Book*hug Press, 2014). Leak‘s poems were soaked with the sweat of justified twenty-something anxieties; its nippy sense of punning humour was more teeth-in-cheek than tongue-in-cheek. Tend carries forward some of that body horror-based dread, and much of the linguistic fascination, but Hargreaves’ focus now seems more generative than critical. Where leak was grasping at something forever slipping away, tend succeeds in planting seeds that promise a full-blooming garden. As the title suggests, there is a great deal of care in tend: rituals performed for loved ones (“I want to make her tea with proper milk / wash the dishes / drive her car / collect her after visiting hours / circle her in salt”), conscientious management of one’s effect on the environment (“I will be a person who composts […] I will wash and sort my recycling”), or even, paratextually, the attentiveness with which Hargreaves has designed the cover of the book. Much of the care expressed is aspirational rather than actualized — a tendency rather than a perfect practice — but these are poems that gaze toward futures: of the self, of public transit, of bumblebees.

When a book has already won a Governor General’s Literary Award for English-language Poetry, as Annick MacAskill‘s third poetry collection Shadow Blight (Gaspereau Press, 2022) has, a review seems like such a small afterthought. Yet when I return to these poems, I think that another round of praise is precisely what this book deserves. From the opening lines (“The tulips give up the ghosts / of themselves, their petals supple boats / on my window ledge and table”) to the closing (“but the centre of you / was white and blue / a star”), this is a lyric collection in the most literal sense of the word: melodic, rhythmic, finely tuned, a pleasure to hear aloud even if you discount all of its other qualities. That the book is simultaneously emotionally devastating (as when the speaker says to her unborn child “there you were / shuddering / into the toilet bowl”), culturally resonant (“Priam / is to eat before he wails, / as Niobe attended to her own body / before returning”) and formally and tonally surprising (“SMEAR THAT FERTILE PULP / ON MY FACE O PRIEST”), makes it a nearly perfect book. Even what felt to me, at first, like the collection’s one drawback — that it seemed just a little too spare, as if it ended too soon — I soon saw was also exactly right. For how could a book about miscarriage finish in any other way?

I nearly overlooked Natalie Hanna‘s debut poetry collection lisan al’asfour (ARP Books, 2022) when it came out, but by happy accident a month ago that I was reminded of its existence, and how grateful I am to the inscrutable hands of fate or chaos that brought me to this book. Though it resists the contemporary impulse toward a unified and marketable premise, lisan al’asfour has distinctively compelling features. For one: its lovely use of language, especially its employment of half-rhyme, assonance and euphony, as for example in “what do i care / for the worries of ants and the sleepy bees / when i too am so empty of honey.” (Appropriately, the book’s title, lisan al’asfour, is Arabic for “the bird’s tongue,” a phrase that evokes the concept of the poet as nightingale, a bird known for the beauty of its song.) Beneath the beauty of the poetry, however, is an incisiveness and a willingness to use that incisiveness to confront difficult, or even irresolvable subjects, be that cultural friction within the family unit (“softly i say, to soothe mother’s rage / that belonging nowhere is a parcel of stone / bestowed on newcomers’ children”) or the “occupation” of Ottawa during the pandemic (“the miasma of rage / barking sheep into their faces / breaking the back / of the hard-won line / my body my choice“). One of the aspects of the collection that is most impressive (and urgently needed) is Hanna’s ability to turn judicial proceedings into critical art, as for instance when the speaker of ‘peremptory challenge’ addresses the judge of the “trial for the death of Colten Boushie”: “peregrine praetor / you might as well be / for your strangeness / with the customs of the land / where you have settled.” Lisan al’afsour brings together the varied aspects of Hanna’s expertise — poetic, diasporic, legal, et al. — into one collection that challenges even as it soothes. I’ve already started making a list of people I’ll be gifting copies of this book.

2021

Horses Drawn with Blue Chalk, translated by Jessica Sequeira (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2021), is a bilingual chapbook that constitutes the first presentation of Bolivian philosopher-poet and editor Rocío Ágreda Piérola‘s work in English. With the Spanish and English translations presented tête-bêche, the chapbook includes poetic selections from Ágreda Piérola’s previous collection, Detritus, and the as-yet-unpublished Quetiapine 400mg, as well as a ‘Translator’s Note’ by Jessica Sequeira that helpfully contextualizes the work as a fusion of lyrical and avant-garde traditions, and a “slantwise” fit in a lineage of Latin American writing. Horses Drawn with Blue Chalk is a heady mix of academic references (“I dream of a man from Kiev reading Spinoza in prison”), cosmic contemplation (“How could I not come out flying / with the infinite sea of electricity. / How could I not plug myself at the last moment / into the tide”) and bodily immediacy (“little scene of hunger / where it digs and digs into the fortress of myself”).

Joey Yearous-Algozin‘s latest collection, A Feeling Called Heaven (Nightboat Books, 2021), exists somewhere between dream, irony and ecopoetic anti-capitalist treatise (not unlike Ryan Fitzpatrick’s 2023 collection Sunny Ways). Formally, the collection reads as a very long poem (under the heading ‘for the second to last time’) followed by a shorter long poem (‘a closing meditation’), and it fixates on what it seems all contemporary poets are required to reckon with in their work: impending apocalypse and humanity’s role therein. Yearous-Algozin’s tone is compellingly difficult, shifting uneasily between paradoxically affectionate blame (“it’s not despite the destruction of the world / that you’re worthy of love / but because of it / because you’ve helped to usher it in / through these minor acts of annihilation”) and flippant detachment (“I want you to remember that violence is just information / or decorative like a video”). Take from this what you will: twice in my tenure as Reviews Editor, we’ve had a reviewer return a book because they didn’t feel they could respond to it, and A Feeling Called Heaven was one of them.

It cannot be said that I am a contrarian, for this is the second time a winner of the Governor General’s Literary Award for English-language Poetry appears on this list. Once again I must say: the honour was amply deserved. Tolu Oluruntoba‘s poetry collection, The Junta of Happenstance (Palimpsest Press, 2021), is a remarkably eloquent and controlled debut. Though it is audaciously political, perhaps even at times polemical in its critiques of capitalism (“Even security camera clerks hate their jobs, / so what would it take for this arbitrary economy / to block an artery and die?”), settler-colonialism (‘”When Migrants Gather to Enjoy / the plunder that preceded us, / the eyelets, fishhooks of the dead / try to snag our glances”), et al., Oluruntoba’s work is far too adroit to ever be mistaken for propaganda. The language here is stunning, the humour, when it comes, is grim and the subjects, on the whole, are dire. If that’s the sort of poetry you enjoy (it’s certainly the sort of poetry I enjoy), then it’s difficult to recommend this book highly enough.

On the other hand, if you prefer your political poetry served alongside profuse pop culture references and a side of cheer, you’ll want to check out Charlie Petch‘s Why I Was Late (Brick Books, 2021). Petch has a long history of multidisciplinary work in spoken word, theatre and music, and that shines through in these buoyantly funny poems that beg to be read aloud. Some poems are seemingly meant solely to entertain, like ‘Eat Prey Love,’ a poem “To be performed with an insect voice & stance” because, well, it’s written from the P.O.V. of a praying mantis, and opens: “Victor / six hours of straight lovemaking is a lot.” But that rollicking poem is bookended by ‘Life Is Easier When I’m a Misogynist,” in which a transmasculine speaker reckons with their complicity in sexism, and ‘Electric,’ about the ongoing failures of an employer and a union to adequately protect workers from physical harm. Why I Was Late is a funny, moving and accessible book. It’s also deeply relatable for those of us who are queer, trans, disabled and / or perpetually late, like I was writing these reviews.