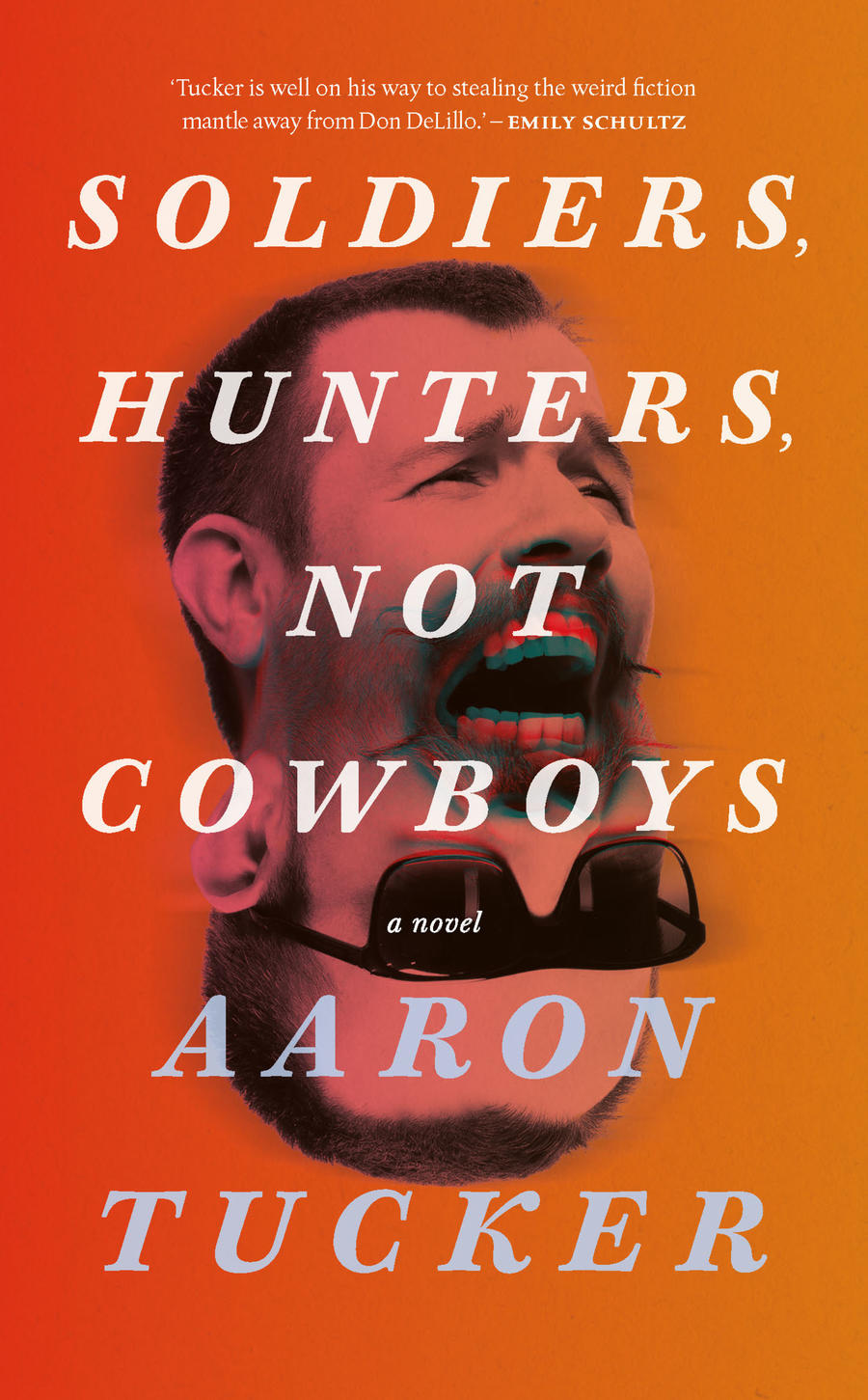

USEREVIEW 127 (Capsule): Soldiers, Hunters, Not Cowboys

Aaron Tucker

Soldiers, Hunters, Not Cowboys (Coach House Books, 2023)

ISBN: 978-1-55245-462-6 | 160 pp | $23.95 CAD / $18.95 USD | BUY Here

#CAROUSELreviews

#USEREVIEWEDNESDAY

Published this spring by Coach House Books, Aaron Tucker’s Soldiers, Hunters, Not Cowboys is a novel divided in two. The book’s first half, formatted as a dialogue between an unnamed male protagonist and his ex-girlfriend Melanie, presents an extended synopsis and commentary on the 1956 John Wayne western The Searchers — both one of Wayne’s most lauded performances and a frighteningly regressive example of mid-century American conservatism. The book’s second half, meanwhile, recounts said protagonist’s paranoid, semi-hallucinated ramble through a 9/11-esque urban disaster area. Nonetheless, both parts centre on the character’s many hallmarks of (white, hetero) toxic masculinity: he drinks excessively, makes excuses for historical racism, gaslights his ex while also creepily fixating on her personal safety, and jumps at any opportunity (real or imagined) to engage in chivalrous violence.

Although the two halves of Soldiers, Hunters, Not Cowboys feature vastly different settings and styles, they also fit together almost too neatly, with the second obviously ‘playing out’ the character traits established in the first. As an author, Tucker excels at conveying baroque, evocative detail — from the sprawling desert buttes of Monument Valley, to Toronto’s gritty Downtown East, to the depraved fantasies of a psyche in collapse. Unlike his previous novel, Y, however, Soldiers, Hunters, Not Cowboys employs this detail more toward illustrating its travelogue than developing character or conflict. Ultimately, the book is focused on its message, which warns of the dangerous collusion between heroic masculinity, anger and violence — as well as the ideological conditioning that allows them to seduce us.

Recommended excerpt:

While the first half of Soldiers, Hunters, Not Cowboys critically examines the marriage of nobility and brutality in John Wayne’s acting, its second half dramatizes this archetype through its unnamed protagonist’s fantasies. An example (p. 89):

He wants to have not missed it, to have lived through it so that he could tell others what it had been like, how he rushed out to the street to look, braving the stampeding crowds and the unknown; he wishes that he were right on the edge of the flames, within the immediate impact. In his fantasy, he is at the centre of the carnage and wreckage, the violence of it, and is now recounting it calmly, under the glistening rapt attention of an audience, Melanie’s vivid eyes.