USEREVIEW 135: Symptoms of Acute Excellence

CAROUSEL — New Patient Evaluation

Referring Provider: NeWest Press

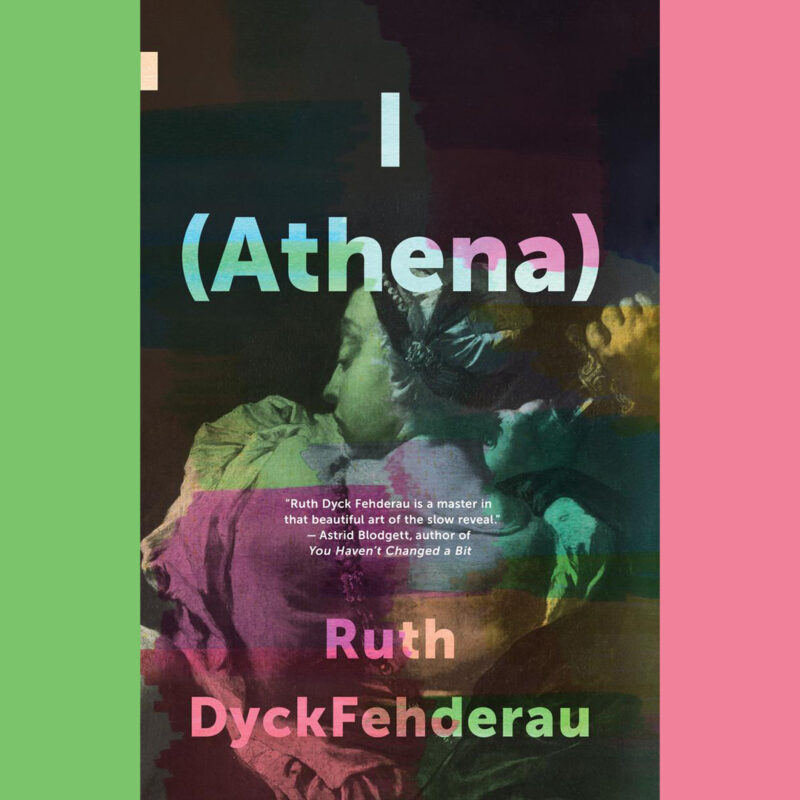

Patient Name: I (Athena)

Parent/Guardian: Ruth DyckFehderau

Date of Birth: April 2023

Weight (in pages): 352

Height (in ISBN-13): 978-1-77439-068-2

Attending Physician: Emily Woodworth

ASSESSMENT

I (Athena) presents with symptoms of acute excellence. Patient is well-composed, making perfect use of voice, found-form composition and sentence-level beauty, with just enough suspense to exceed standard expectations of momentum for a patient of 352 pages.

Examination of subcutaneous layers reveals use of unreliable narrator and interrogation of the ways narrative and memory interact (re)iteratively. Though sometimes unreliable narrative can progress to pathology, in I (Athena)’s case, no pathology was detected: unreliability is integral to the patient’s underlying structure, and did not sink to the level of trope at any time during our interaction, instead elevating the patient’s performance on all tests administered.

DIAGNOSES

Primary Diagnosis:

I (Athena) exhibits many elements of compelling character syndrome, exhibiting complexity within each character the patient developed. The patient’s particularly compelling primary character is Athena, a deaf woman recovering her individuality and agency after decades spent in an institution (Holdstock Facility).

Connected to this primary character is a secondary main character: a girl named Verity. Upon questioning, Athena quickly reveals that Verity is Athena herself as a young girl, growing up mistakenly institutionalized after an illness leaves her deaf and she is misdiagnosed as “profoundly retarded” by medical practitioners in the 1960s. Athena exhibits no access to the part of her that was Verity, and this inaccessibility creates great narrative energy: Athena’s memories are lost to time and the fog of being over-medicated for years, and Verity’s existence is demonstrated only by indirect means, like newspaper clippings, letters, interviews and medical reports, whose reconstruction into narrative by Athena reveal as much about Athena as they do Verity’s factual experiences.

As Athena works to reconstruct Verity’s reality, consulted documents are often included directly in the manuscript and lend themselves to developing even more characters, at an even greater depth, while never straying far from Athena’s central role in selecting and shaping the memories into narrative. These past sections seeking to understand Verity mainly involve Athena’s father Esau, who committed her, and a nurse at Holdstock Facility named Harriet Caulle, who compellingly gives a face to the often-inhumane practices in institutions of that era.

Esau is an enigmatic character as written by Athena. She chooses to uncover everything, from his childhood to his decision to commit Verity (without her mother’s involvement). As Athena strives to understand this decision, a complex image of Esau emerges, including his war-time romance and abiding love for a man named Michael, and eventual journey to end up with Verity’s mother, Jude. Disability crops up several times in this narrative, including its impact on Esau’s sister and Michael’s brother.

Nurse Harriet Caulle is the other indirect source for information on Verity’s life and the deteriorating atmosphere at Holdstock. Rather than being a one-dimensional Nurse Ratched-type character á la One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Harriet Caulle is explored by Athena as someone who slowly allows herself to accept lower and lower standards through a sort of idealistic haze, convincing herself that reducing harms and mitigating the worst abuses of the system is actually an altruistic approach that absolves her of the abuses still required by the director of Holdstock Facility as he tries to cut costs. Her journey down the path of dehumanization takes place on the ironic backdrop of Caulle’s worsening mental health issues of her own.

After these two narrativized sections, a third documentary set of records about Verity is produced by a group home worker, Uly Banner. Unlike Esau and Harriet, these are given from Uly’s own perspective directly. Still, this more empathetic voice is not altogether without intrusion. Athena notes at one point, “I am so tired of seeing everything from the perspective of the system without them and their great machinery ever seeing it from mine,” a sentiment that gives added weight to her efforts to formulate herself into narrative in order to be seen.

Indeed, it is necessary for I (Athena) to break away from pure “historical” documentation in order to maintain momentum. This is likely why I (Athena)’s guardian, Ruth DyckFehderau, has intelligently tasked her with composing journal entries (spanning 2003–2004) regarding her life parallel to her work on reconstructing Verity’s life. And so her search for herself (as Verity) is shadowed by a search for her purpose outside of Holdstock Facility (as Athena). DyckFehderau gives Athena a present-day quest that sets her on a course to be forced to continuously reevaluate her conceptions of herself and of society.

Athena speaks of this other project on page 26, saying,: “Imran, my Independent Assisted Living worker and friend, thinks I should journal about my other current project … My other project, then, is this: I have decided to try for custody of Arvo who was my companion through my years in the Facility.” As Athena pursues custody of Arvo, DyckFehderau also places Athena in therapy, forcing her reassess her writings on Verity, her father and the Facility, as well as her navigation of present-day bureaucracy. Athena’s journals provide insight into her emotional and psychological growth, while also illustrating moments of her daily life and relationships as a deaf woman navigating Canadian society alongside her key worker Imran and delightful neighbour / owner of a XXX store, Mr. Saarsgard.

Besides the journal entries, Athena also provides ‘Writer’s Notes’ to preface certain sections concerned with Verity in order to highlight the aspects of these sections that may be subjective. All of these elements open a wide avenue into Athena’s thoughts, allowing I (Athena) as a whole to appear to flow directly from this compellingly unreliable narrator in a way that is totally organic, internally consistent and incredibly well-executed.

Secondary Diagnoses:

The patient displays obsessive-thematic traits, most often concerned with (re)constructed memory / narrative and disability.

As Athena investigates, she also questions the accounts the finds, interrogating the reliability of her own narrative and memory. This is often subtly or directly addressed in the text. In one instance, Athena discovers a newspaper article about five former bullies from her father’s hometown who went to war and were memorialized as heroes when they didn’t return, complete with a statue in their honour. After finding that the journalist who wrote of them later confessed that the bullies never apologized for their bullying, Athena reflects: “I wondered then about those who had been bullied … Did they feel belittled every time they walked by the monument? By the ways their ugly realities had been forged and recast? … Or did they alter the story in their own memories so that they, too, could have something to lionize, something to admire?”

Disability colours many different characters’ lives, allowing readers to see this theme through time, from Esau’s sister who deals with seizures and wheelchair access in a pre-World War II society, to Michael’s brother who is left disabled as an adult and cared for by Michael after he returns from the war, to Harriet Caulle in the 1960s through the 1990s, who dutifully avoids labelling her own agoraphobia even as she holds and over-medicates patients in Holdstock with similar diagnoses. And, of course, Athena’s own navigation of being deaf in a world built for the hearing, and Verity’s relationships with fellow patients with various diagnoses.

These obsessive-thematic traits give an even greater weight to I (Athena)’s primary diagnosis of compelling character syndrome, pushing this patient into a reckoning with society, disability and memory that is at once fascinating and entertaining.

TREATMENT PLAN

I am prescribing that I (Athena) should be examined by those concerned with the history of disability, memory and narrative, and those who enjoy great fiction. Her guardian, Ruth DyckFehderau, should be congratulated on her exemplary work in helping I (Athena) transition toward thriving in an independent environment by allowing her true strengths to shine.