USEREVIEW 138: Grasping for Magic

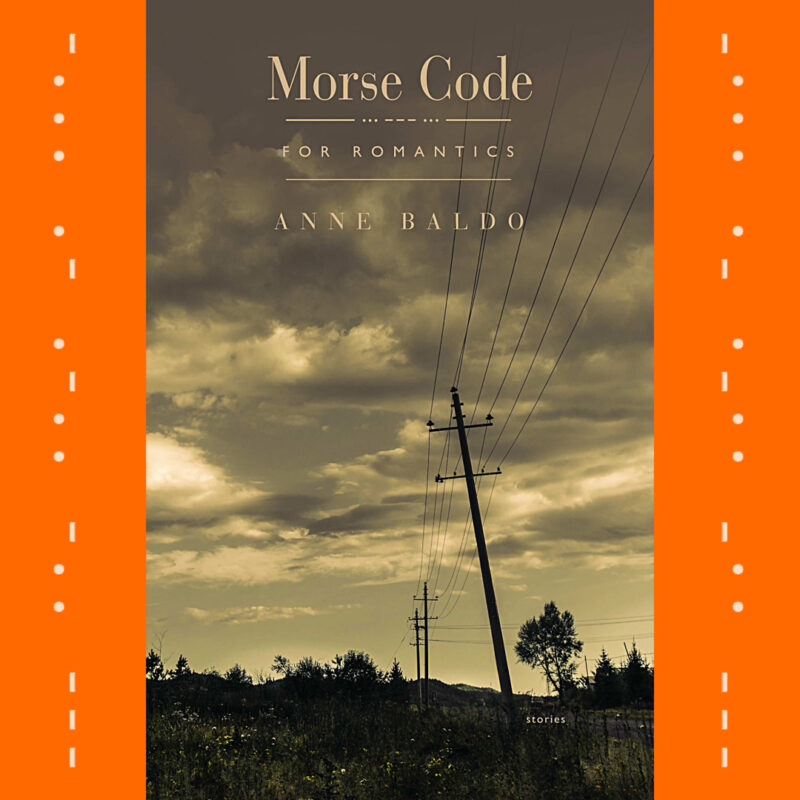

Jade Wallace maps the Southern Ontario Gothic geographies of Anne Baldo’s debut short fiction collection Morse Code for Romantics (The Porcupine’s Quill, 2023).

ISBN: 978-0-88984-456-8 | 208 pp | $19.95 CAD — BUY Here

#CAROUSELreviews

#USEREVIEWEDNESDAY

Lately I have sensed a revival of interest in Southern Ontario Gothic. In the past couple of years, multiple fiction debuts such as Erica McKeen’s Tear and Brooke Lockyer’s Burr have deftly employed the genre to tell contemporary stories, and to that list I would now add Anne Baldo’s long-awaited short fiction debut Morse Code for Romantics.

Baldo is a Windsor-based writer whose work has been quietly appearing in a variety of well-known Canadian literary magazines from SubTerrain to Qwerty, as well as ambitious newer venues like Hermine, for the past eighteen years. She has been longlisted for the CBC Nonfiction Prize and has been a finalist for Malahat Review’s Open Season Awards for fiction. I’ve personally been eagerly awaiting a full-length collection since her languorous, shimmering ‘The Happiness of Robots’ appeared in CAROUSEL, and Morse Code for Romantics more than fulfilled my expectations.

Baldo is a writer clearly preoccupied, at least during this part of her career, with exploring particular themes. Stories like ‘Last Summer’ and ‘Concession Roads’ poignantly capture the brief, flinty flash of youth, in all of its longing for something unnameable and its imminent and inevitable fading away. ‘Oh How We Miss You, How About Joining Us?’ and ‘Fish Dust’ examine the complex dynamics of gender, desire and power, particularly as they are experienced by women in small towns who are of limited means.

These are not extraordinary themes — rather the opposite. They are completely, strikingly ordinary. What sets Baldo’s work apart is the way she writes. There is of course the gothic touch. ‘Marrying DeWitt West’ is perhaps an especially good example of this. Told using a dual-perspective he said/she said approach, the story is a taut and tense recounting of the titular DeWitt’s visit to a small community on the shore of Lake Erie, where he believes a sea monster might be living. Once there, he exploits the curiosity and naivete of a young local girl, using her both as a navigation guide and as a romantic dalliance. The sea monster is the pretext, but the story is really about plumbing the depths of moral ambiguity, particularly when DeWitt meets the black-laced hands of fate.

There is also Baldo’s exceptional attention to the language she uses. It is not at all surprising that Baldo writes poetry as well as prose, for your can hear her aptitudes for lyricism and imagery in so many lines throughout this collection: “We were iridescent with sweat, haloed with August heat.” The endings of these stories in particular are poetic, preferring ambiguous, imagistic closing lines, full of emotional resonance, to a more neatly traditional version of denouement and closure:

“Does that work?” I ask.

And he says it does, sometimes. And maybe it is true. Maybe we would find each other one day, too, somewhere in the clouds, in a sky without stars.

Baldo also has a particular knack for that lovely trick short story writers are always trying to pull off: drawing upon strange and unusual facts and turning them into analogies for whatever is happening to the characters. See for instance the opening paragraphs of ‘Monsters of Lake Erie’:

I saw a documentary on the Loch Ness Monster when I was twelve years old. A researcher explained for the cameras how they were searching the murky lake with sonar equipment. They could see down into the depths that way, using sound waves.

[ … ]

I thought when you had been lonely for a long time you gained a similar sort of ability with people. To look at them, beaming out a silent pulse, and be able to glimpse the dark, monstrous shapes of their own loneliness lurking beneath the surface.

That there could be a whole story in itself.

What is most remarkable about Baldo’s work, however, is far harder for a simple reviewer like me to explain, so I’ll try to show you. Let’s look at the opening paragraph to ‘Motel Mermaids’:

Liss said, “We are motel mermaids. We are made of magic.” Which sounded better than the reality that we were housekeeping for the Blue Haven Motel on an island in the middle of Lake Erie.

Many of the characters in Morse Code for Romantics are like Liss. They dream, they euphemize, they throw glittering veils over their shoulders and their tables and their friends. They are ordinary people grasping, often vainly, for magic, amidst the banality of their surroundings. But where they fail, Baldo succeeds. These are stories that bring a touch of enchantment to this far corner of the province that no one wants to visit and everyone wants to leave.

There is melancholy, of course, and decay, and hopeless longing in these stories; this is after all still essentially gothic literature. But Baldo makes a reader want to go on living here — between Lake Erie and the Detroit River, on the southwesternmost edge of southwestern Ontario — in spite, and sometimes because of, the forces of economic and existential decline that stand in our way.