LGBTQA+GTA

In 2019, CAROUSEL interviewed five writers whose origins spanned the globe, whose ages straddled generations, whose writing practices crossed genres and genders, but who were all akin insofar as they were then at work making queer poetry in the GTA. The essay based on those interviews appeared in full in CAROUSEL 42, our winter 2019/20 print issue. What follows is an abridged and lightly edited version of that essay.

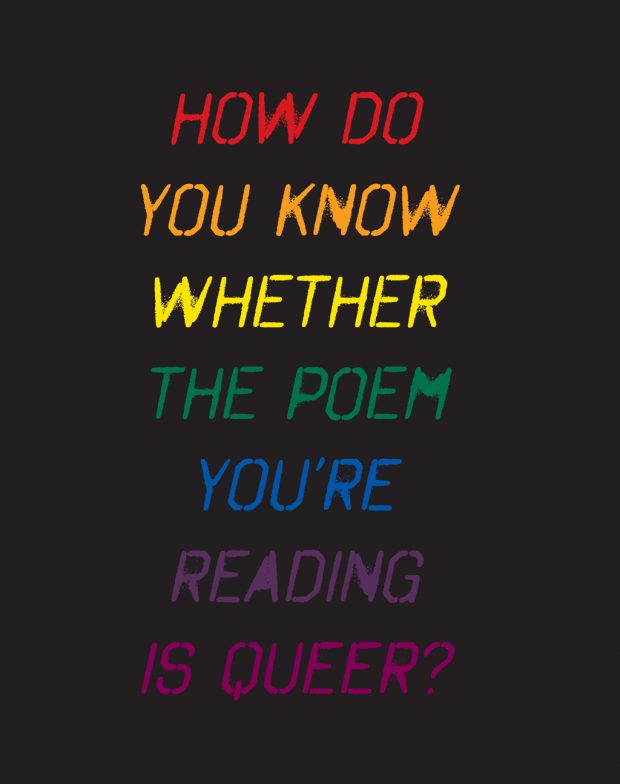

How do you know whether the poem you’re reading is queer? Bänoo Zan, poet and organizer of Toronto’s Shab-e She’r (Poetry Night) reading series, takes the simple but radical position that, “Poetry, by its very nature, is queer. It deconstructs narrative. It is the product of a mind that can imagine lives not lived.” Fiction, of course, also imagines lives not lived, but typically it imagines discrete lives led by identifiable characters. For Zan, poetry has the capacity to generate innumerable lives and characters within each poem by virtue of its ability to refuse to specify or narrow its intent. For instance, many languages let the poet to be vague with respect to the gender of the speaker and other figures. Thereby, Zan says, “the language opens itself up to a multiplicity of identities and gives permission to the writers and readers alike to be subversive,” allowing not only the writing but also the reading to become “a more creative and revolutionary act.”

She contrasts this with less generative languages, in which “the poet’s choices are limited to explicit manifestations of gender. Hence, the poet needs to decide between the available options and loses the chance of including everyone.” This type of language resists the openness and the queer potential of poetry and instead becomes a gatekeeper to both writer and reader. As Zan puts it, “A language that forces you to ‘identify’ yourself and your subject, is asking for your ID card before it lets you in.” Whether all poetry is successful in deconstructing narrative and bringing a multiplicity of lives to blossom, as Zan suggests it should do, is questionable, but perhaps the implication here is that the most open poetry, the most essentially poetic poetry, also has the greatest capacity for queerness.

Other writers take the position that poetry must be more purposive in order to be queer. Poet and translator Khashayar Mohammadi posits that “any writing that aims to subvert the heteronormative narrative is queer regardless of the sexual orientation of its writer.” Comparably, poet and archivist Tanis Franco suggests that in queer poetry “there is an intersectionality, a willingness to break down any traditional thoughts of gender, sexuality, etc.” Queer poetry, by Mohammadi and Franco’s definitions, could be said to be poetry that is attentive to how identities exist and interact and challenges assumptions about what those identities entail. Franco acknowledges that this interrogation of gender and sexuality is not necessarily restricted to queer poetry but suggests that it may be more pervasive there. “Being genderqueer and queer, this is with me every second of the day. It changes the way I act in public. There is so much infused in a queer body. This space also extends to the written page.”

The position taken by Franco and Mohammadi is seemingly very different from that of Kirby, poet and owner of the poetry-only bookstore knife|fork|book. Kirby recalls his initiation into queer literature, which, at that time, could “be found tucked away inside the ‘Gay/Lesbian’ section of any commercial mall bookstore or under ‘H’ in the library card catalogue.” When he ventured into performance, Kirby’s first readings were at the Rivoli and the Cabana Room. “One of my favourites was at the spa on Maitland where we passed around poppers.” For Kirby, queer literature is constituted not only socially, but also geographically and spatially. Only once he had become aware of where to access queer poetry could he then pursue it in its more abstract significance: “Then it had to do with finding my people, those brazen enough to write queer stuff in the time of liberation, not assimilation, and I guess that’s where the divide is now, those poets/writers that continue to stir/stoke the queer imagination.” Queer poetry, for Kirby, occurs at the nexus of queer space, queer identity and the liberating impulse of the queer imagination.

Poet Kamila Rina also notes the significance of communal and individual identities as crucial to queer poetry. Rina defines queer poetry as “Basically, anything that’s explicitly gay, lesbian, bi/pan, trans, non-binary, ace or aro — or anything that’s a big part of the queer cultural sensibility but isn’t valued/noticed in the mainstream.” For Rina there is more to queer poetry than just categorical identifications, there is also a ‘queer cultural sensibility’ in the work that subverts, or perhaps just provides an alternative to, the mainstream mores regarding gender and sexual orientation.

It is perhaps this ‘queer cultural sensibility’ in which we glimpse some common factor that can help us begin to identify queer poetry. Though the writers disagree on whether the identity of the writer or the context in which the writing is produced are crucial to its queerness, there is nevertheless a similarity in the way the writers describe the animating forces of queer poetry. Rina’s emphasis on attentiveness to non-normative queer concerns within a work is not unlike Kirby’s vision of a queer imagination that is impelled by collective efforts at liberating thought, or Franco and Mohammadi’s intentional breaking down of gender, sexual categories and heteronormativity, or Zan’s openness to creating a multiplicity of identities and meanings.

Unlike the classification of queer poetry, which permits a great deal of communal pontification and enduring uncertainty, the decision of whether to describe oneself as a queer poet is an intensely personal choice and also one that cannot be deferred indefinitely. One can choose to explicitly identify as a queer writer or not; one can repeat — and change — this choice with every author bio they attach to a publication and every interview they give; but still one must make the choice. The reasons informing a writer’s decision about how to proceed are extraordinarily varied.

Kirby, for instance, says, “I’ve never called myself a queer writer. And there’s not an iota of me that’s other than queer. A poet approached me once after a reading saying, ‘Kirby, you’ve been doing this for a while, how come we haven’t heard of you until now?’ And that’s because I primarily read in gay venues to gay audiences, though not exclusively.” For Kirby, it seems, there is no need to call himself a queer writer because his mode of practice speaks for itself. The content of his writing, the identities of the assumed and actual readers, the spaces in which he makes his work available, and the way he presents himself in all aspects of life, not just in writing, make clear that both Kirby and his work have “had to translate the ‘non-gay’ world into something of interest.” There is simply no cogent way to interpret his poetry as being other than queer.

By contrast, Khashayar Mohammadi has nearly diametrically opposed reasons for making the same decision to not call himself a queer writer. He says, “I personally identify as queer, but I often feel uncomfortable marketing myself as a queer poet since a lot of my poetry is not explicitly queer.” While Kirby’s work is so inarguably and overwhelmingly queer that he feels no need to don the label, Mohammadi feels it might be misleading to label his poetry queer since that is not one of the obvious or overriding concerns of his oeuvre, even though it is a recurring theme that is obvious enough to an astute reader.

Zan, likewise, is somewhat cagey about calling herself a queer writer, though her reasons are different again from either Kirby or Mohammadi. Zan writes: “I approach topics such as religion and culture through different lenses, including queerness. I also approach queerness through the lens of religion and culture. I dialogue with identities, affirm, analyze and subvert them. My poetry is the voice of conflicts and blurred lines. It attempts to escape from linguistic and stylistic straitjackets.” Zan, committed to her stance that queer poetry is a poetry of openness and multiplicity, finds the label of queer writer too limiting and thus, ironically, not sufficiently queer. She does, however, recognize that typically “Readers and reviewers do not address the queer unless the poets explicitly identify as such.” She thinks that this is a mistaken approach and advocates instead for addressing the queer potential of poetry regardless of the identity or intent of the author. As she says, “I believe writing is permission enough. As soon as a writer publishes or shares their work, they are permitting, and, in fact, inviting people to dialogue with the work. Attempts at suppressing interpretation are against freedom of expression, and so are attempts at censorship.”

Franco, though similarly motivated by political and social concerns, has opted to adopt the label of queer writer. In fact, they say, “Right now it’s imperative to me to be identified as a queer writer. In the US and elsewhere our rights are being taken away — our very existence is being erased and denied. It’s maddening, and also heartbreaking. More than ever I think it is important to confirm our humanity.” Unlike Zan, Franco does not rely on the imaginativeness of their readers, but seeks to specifically confirm their own situatedness as a queer writer and thereby also to make undeniable the queer representation occurring in their work.

Rina, like Franco, also finds identifying as a queer writer unavoidable. However, for Rina, the label of queer writer was not perhaps so much a stand-alone choice as it was the result of a sequence of prior choices regarding the content and context of their work. Rina explains, “All the poems I wrote were explicitly queer poems, where I couldn’t hide their queerness — and/but/also it also didn’t occur to me to try. Everyone in my life was queer. Everyone who would read my work as a beta reader, whose opinion I valued, was queer. And when I started submitting my work for publication, I sent it, out of necessity and comfort, only to queer-friendly or queer-centred publications.”

While they may not agree about what constitutes queer poetry or whether to categorize themselves as queer writers, the interviewees were unanimous on one point. When asked where queer poetry exists in the GTA, they replied: everywhere. Rina provides illustrative examples when they say that queer poetry exists “in little zines sold by young people at community markets, in Facebook posts I see from friends and acquaintances, in sharing newly written poems with friends and loved ones who are also poets, in the readings I go to, in short lines stencilled onto the sidewalks in the west end that I found out were stencilled by a local queer poet/artist.” Zan echoes Rina’s sentiment about the pervasiveness of queer poetry, noting that it is “in the line-up of many events that may not label themselves as such, as well as in the open-mics. Almost any anthology of Toronto writers includes queer poets and/or queer poetry.” However, Zan is somewhat more circumspect about how easy it is to recognize queer poetry. She opines that, “Readers and critics need to approach works disregarding the official bios of the poets. Some may not be out, but their work is out there.” While Rina is engaging with spaces where the queerness of poetry is known and emphasized, Zan seeks queer poetry also in spaces and texts that do not identify themselves as such. This makes sense given Zan’s belief that all poetry is queer, or at least is capable of being queered through creative and revolutionary reading and interpretive practices.

Queer poetry, though so evidently prevalent, nonetheless remains flittingly elusive at the same time.

You can also check out our poets’ Queer Lit Reading List.

The article LGBTQA+GTA

appears in CAROUSEL 42 — buy it here