USEREVIEW 019: Playing with the Universe

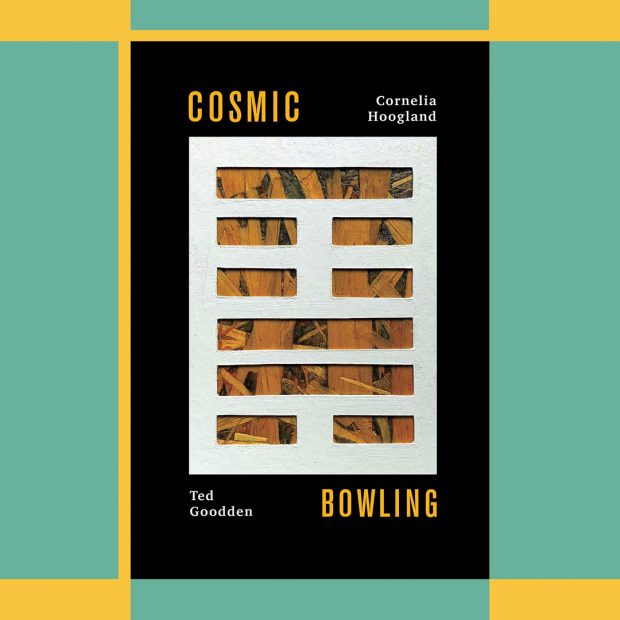

In this exuberant traditional review, Julie McIsaac traces the metaphysical, mythological and scientific lineage of Cosmic Bowling, a collaborative art and poetry collection by Cornelia Hoogland and Ted Goodden (Guernica Editions, 2020), while simultaneously imitating the spirit of playful wonder that animates the book.

ISBN 978-1771835374 | 156 pp | $20 CAD

#CAROUSELreviews

#USEREVIEWEDNESDAY

Cosmic Bowling by Cornelia Hoogland and Ted Goodden was released in 2020 as part of Guernica Editions’ Essential Poets Series. The collection is a conversation between a poet and a sculptor, triangulated through the I Ching, known also as the Book of Changes. For those unfamiliar, the I Ching is a compendium of Taoist, Buddhist and Confucian thought expressed in pithy six-line stanzas, called hexagrams, which are ordered according to a coin-tossing system. In Cosmic Bowling, Hoogland’s six-line poems are presented on the recto of each page spread, while photographs of Goodden’s sculptures appear on the verso. Each pairing is displayed cleanly and shot through with erudite allusions and evocative contradictions. Goodden’s essay about the historical and personal influence of the I Ching rounds out the book.

Cosmic Bowling is deeply invested in what Goodden calls the I Ching’s capacity “to illuminate the present moment rather than forecast some predetermined future.” In particular, it is the significance of adversity, a force of ambivalence alive in every instance of daily life, which Cosmic Bowling expounds upon and basks within. Sometimes with brazen blatancy a poem asks, “Do you have to be Taoist / to learn adversity’s value?” Yet, most of the book’s poems and images playfully (hence, Bowling) ruminate on the complex forces of push and pull that operate internally and externally, from beneath the earth to the far reaches of space (hence, Cosmic). The beauty of this complexity lies in the brevity of the poems and sculptures and also in the dialogue between the two, which is at once playfully illustrative and also dialectically enriching.

The opening poem, “Ch’ien, The Creative,” sets out the cosmological scope of the collection:

Six unbroken lines forge a white-hot connection.

We’re born for heat. Maybe lava, earth’s

molten core; maybe the sun’s energy.

We human neuro-electric light bulbs,

winking our 100 watts. The six steps equal

six dragons to climb. They are not sleeping.

In this poem, that which is creative is shown at its most basic and powerful: the formation of the Earth — the cosmic energy at the beginning of the world and humanity. Though the “six unbroken lines” anchor the reader’s focus onto the page by foregrounding the literary constraint at the formal center of the work, the subject matter quickly moves out from there. In the first stanza, or trigram as it’s called in reference to the I Ching, “white-hot” planetary forces like lava, the earth’s molten core and the sun’s energy are at the heart of creation, writ large.

The next stanza shifts the focus again, this time to the inside of the human body, while maintaining the same weight of meaning attributed to the cosmos. “We human neuro-electric light bulbs, / winking our 100 watts” illustrates the “white-hot connection(s)” within our body chemistry, our biological complexity and ourselves. Yet, the organic qualities of our beings are always already tinged with humanity’s mechanical discoveries and inventions: light bulbs and their wattages are winking — intense and powerful but as fleeting as can be imagined.

The second poem, “K’un, The Receptive,” works as an answer to and a continuation of the first poem, showing the scope of creational heat writ small on the everyday.

Snow fills the forest framed by the ebony window.

The fairy tale queen

puts down her needlework and wishes for a child.

The season deepens. Hoarfrost numbs the grass, ice

needles the ground. Six cows

in the winter field, their hot breath steaming the air.

In contrast to the heat of the previous poem, this one begins with a wintry scene. Through the frame of the ebony window, the reader is invited to view a tableau along with the speaker, and is cued to see the poem in the same way as the visual artwork in the book: contained and presented in a frame, like an art piece, or photograph, or snapshot. It appears as though “The Receptive” is an inversion of “The Creative,” meant to show the yin to the other’s yang. However, just as yin and yang both contain the seed of the other, “The Receptive” touches upon and also reframes the magnitude of wonder present in “The Creative.”

The image of the fairy tale queen is a trope taken from fantasy — a make-believe invention and a narrative archetype. Though the archetypal quality of this figure speaks to the creative imagination of humanity more broadly, it does so without the gravity of the planetary forces in the previous poem. The fairy tale queen is both a creation and a creative; in her needlework and her desire to procreate, to have a child, she is shown in the continuous act of making. This poem then marks an intensification, as “the season deepens,” that deepening effectively circles back to the profounder themes introduced in the first poem. The ice “needles the ground” like the fairy tale queen worked on her needlework, connecting the handmade with natural phenomena. “Six cows / in the winter field” materialize within the frame as an everyday banality containing all the signs of cosmic mystery; not only are there six of them, a magic and meaningful number, but their “hot breath steaming the air” is a reminder of the heat of the sun, the molten-ness of lava and the neuro-electric currents in us all. This scene is one that can be imagined easily for anyone who has driven down a country road with the car window framing views of the easy landscape, but here the poet imbues it with the same gravity as the previous poem. With an enviable lightness of touch, Hoogland shows how the “six unbroken lines forge a white-hot connection” on and off the page. A simple takeaway could be that there is poetry all around us, but Cosmic Bowling belies the notion of simplicity, insisting instead that around us there is only complexity.

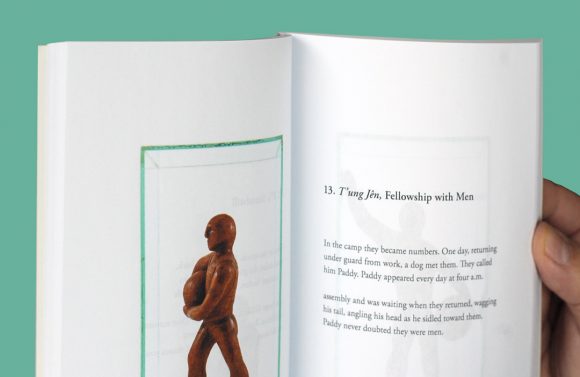

Photographs of Goodden’s sculptures contribute to the complex dialogues at work in the collection. In each piece, a brown human figure of square proportion holds a sphere. In the photographic reproductions, edges of a glass box frame each sculpture. In each instance, the figure is in a different pose, a different emotive state and a different relationship to his sphere.

As one of the book’s blurb writers, poet Patrick Friesen, points out, “The human figure is of the earth, as if it has just emerged,” a sentiment reinforced in Goodden’s essay when he writes: “the world is full of magic — you needn’t look beyond the compost heap to find it”. Certainly, this figure is reminiscent of the compost heap that the book lovingly scrutinizes. However, it also subtly alludes to Sisyphus and Atlas, two mythological figures whose names appear in a couple of the poems. Even without these direct references, the play between the human figure and the ball it holds illuminates the dual centrality of humanity and the earth — that we are of the earth but also separate from it. In this way, the figure suggests a dualism and a totality, simultaneously. Or, in keeping with what is playful in the book, perhaps he’s just bowling?

The poem “Hsü, Waiting” is the first to address the sculptures directly, and at first glance it appears to teach us how to read them:

Light emerges out of these sculptures.

They have their own pulse, steady and below

awareness. Not just the individual images

but the transitions among them. Nothing’s fixed.

The sculptor releases beauty; it will return in another creation.

He’s the accomplice, handmaiden to his work.

The light and pulse emanating from these sculptures, we are told, is imperceptible and of a piece with creation, broadly understood. Just as the sculptures are conduits of this creative energy, so too is the sculptor, here rendered as a mere accomplice to the higher powers at work. The transitions among the still images and the flow of creative energy show us the complexity at work in the pieces. However, the theme of the book as a whole does a thorough job of teaching the reader how to interact with the sculptures. The images are not only illustrations of the poems or the poems descriptions of the images, even if “Hsü, Waiting” suggests that they can be utilized in this way. Instead, Cosmic Bowling’s investment in adversity puts these elements of the collection into a dialectical relationship; each poem and sculpture is unique, sitting still on the page, but also full of contradictions and scrutiny in its relationship to the whole.

For example, the first sculpture, which accompanies “Ch’ien, The Creative,” shows the figure coming up out of the earth, anchored by the ball he holds and stretching towards the sun: the ball roots him to the ground, but also props him up as he lifts his head. In the second sculpture, which accompanies “K’un, The Receptive,” the figure is sinking back into the ground, sitting with the ball resting between his legs. The figure looks towards the ground, resting his hands on the ball in his lap. The two sculptures are opposing — one reaches up while the other settles down, but they don’t easily fit into an up/down dichotomy. Instead, each contains a sense of striving, whether towards the sun or the ground, as well as a sense of futility, in that they can only look at the thing they aspire to and always remain separate from it. The ball hampers and enables their movements. This push-pull motion is ubiquitous throughout the collection, and the sculptures work with the poems to enhance this sense of aversion. The totality of the book circles back in on the individual pieces — poems and sculptures — to teach the reader how they can be read: they are simultaneously congruent and oppositional, static on the page and frantic with energy.

The book’s progression from cover to cover is a circle more than a trajectory, and each poem and artwork obliges a deeper contemplation of planetary magic and the everyday. Cosmic Bowling tells a non-linear story of conversation, creation and contemplation. I admire this work for being unafraid to investigate the largest concerns and unwilling to forgo the simplest.

Julie McIsaac is a maker, artist, writer, editor and momma living in Hamilton, Ontario. She has published two books, Entry Level (Insomniac Press, 2012), a book of short stories, and We Like Feelings We are Serious (Wolsak & Wynn, 2018), a poetry collection that was longlisted for the 2019 Gerald Lampert Memorial Award and shortlisted for a 2019 Hamilton Literary Award for Poetry.