USEREVIEW 028: Loss for Words

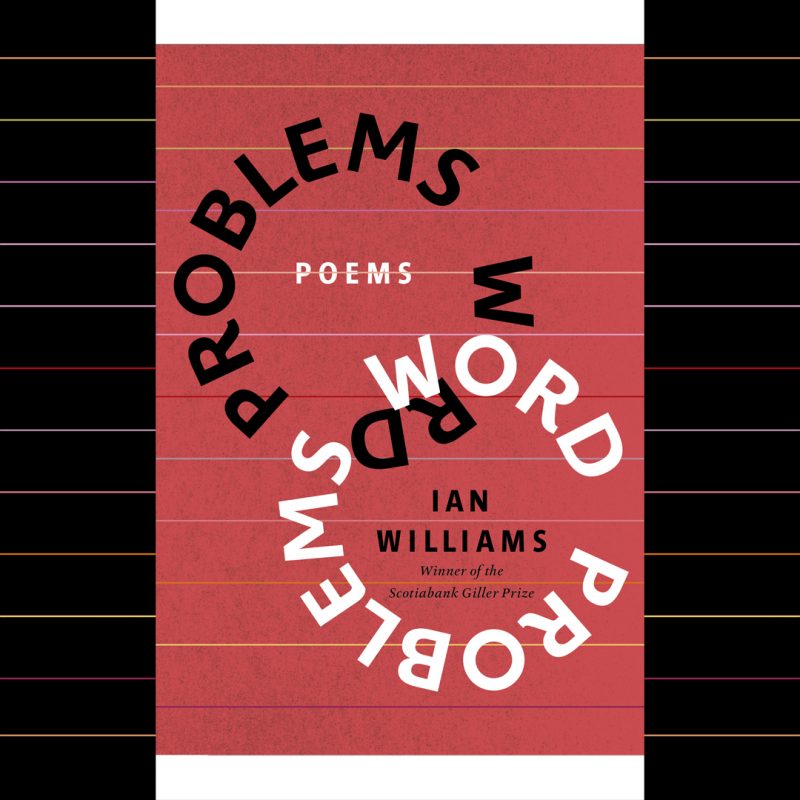

John Nyman parses, calculates and looks for linguistic solutions in this traditional review of Ian Williams’ poetry collection Word Problems (Coach House Books, 2020).

ISBN: 978-1-552454145 | 96 pp | $21.95 CAD

#CAROUSELreviews

#USEREVIEWEDNESDAY

Showcasing a wide range of formal experimentation, an obsession with the technical aspects of language and short, often sentimental lyrics voiced by everyperson speakers, Ian Williams’ poetry is driven by postmodern stylistic devices canonically linked to distancing an author’s identity from the production of literature. By rerouting this legacy into a poetics that has increasingly centred Blackness, Williams also conspicuously risks the erasure of his own identity as a Black Canadian writer. More precisely, he risks compounding the erasure already faced by Black Canadian writers in a predominantly white literary landscape.

Undaunted, however, Williams addresses this risk on every single page of Word Problems, whose margins are infiltrated by prose text (always uncertainly related to the poems it straddles) that interrogates precisely the difference race makes: “suppose,” it begins, “you are a black man who is supposed to be white.” Reflecting Williams’ enduring attention to the marriage of function and form, the typographical out-of-placeness of this haunting commentary exemplifies the conflict faced by many of Word Problems’ speakers, who struggle to assemble racial identity, mental health and interpersonal relationships into coherent life stories. Across their strivings and setbacks, Williams’ decisive accomplishment is to expose and dwell in the infuriating ambiguity of what makes us who we are.

Following the theme of its opening and title poem, which is formatted as a series of short answer exam questions, Word Problems’ poetic style dramatizes its speakers’ tumultuous relationships with language — whether they’re conforming to it, abusing it or being abused by it. Eschewing semantic and syntactical precision, Williams crafts exuberant linguistic performances that spill over line and sentence breaks, instead taking form at the level of the stanza. Here, improvised sequences of false starts, typos, non sequiturs and code switches jostle in a tragic struggle to create sense. “Midas” begins:

Wouldn’t it be nice the textbook

said never use nice if I came to the end

of a thought or a sentence whichever came

first and the curls of your hair turned

into cryptocurrency. Burst would be

a better word than turned. Oh, lorem ipsum

dolor. Too late.

On one hand, the poem’s self-effacing impulse and deliberate messiness are reminiscent of student essay writing, which in turn evokes the patterns of racial and class inequality often symbolized by public education in North America. The schoolkid’s dilemma of encountering language as a concrete, literal problem is further emphasized by Word Problems’ nearly ubiquitous use of unconventional formatting and visual annotation, including emoticons, handwriting, a fingerprint, sound visualizations or “voiceprints,” vertical and diagonal text and Williams’ trademark ring-shaped phrases. Nonetheless, Williams’ style also resonates beyond the elementary school classroom in signalling one of the enduring intellectual struggles of the liberal humanities: to hold language to its promise that it can coherently relate experience.

Finding in that promise both a punishing longing and profound disappointment, Williams’ speakers wear language like ill-fitting hand-me-downs. The versions of formal, functional, descriptive and onomatopoetic diction that dominate Word Problems clang against reality like broken tools. But this is exactly the point: that the clang is more real than whatever it was meant to depict. More often than not, Williams’ technique cuts through its own deliberate erraticism to deliver faithful portrayals of sensation and memory. The opening of “Affect | Affection” is among my favourite examples:

The Beatles. Any time

she heard ‘In My Life’ she would hum it for the rest

of the day especially, Though I dada dada dada

dadaffection. And the guitar lick. The cobblestone

Baroque bridge. The falsetto bit. She would

especially hum all of it.

I don’t think I’ve ever heard the muddy timbre of bad a cappella so crisply — especially in that droning, attention-baiting modifier, “especially.”

In general, Williams excels at using the texture of language to approximate experiences that transcend language — while at the same time emphasizing language’s failure to accommodate that experience. The sheer accumulation of text in “Corrections,” thick with circumspection and delay, bears the weight of a friend’s untimely death for a speaker who is otherwise at a loss for words:

An accident, they she his girlfriend

his ex-girlfriend maybe by now, told me, called to tell me,

texted me. Sorry to have to tell you this by text. It happened

like that this morning, that morning. That happened

that morning. About this time. Sorry to have to tell you …

Word Problems’ first of two sections successfully focuses this style onto two major topics: depression and love, or what “Cliché” refers to as being “a man in dopamine.” Where the collection really stands out, however, is in its second half’s expansion of Williams’ technique to the more inter-subjective and societal issues surrounding Black identity. Consider how “Hair is Choking the Drain” invokes the same stylistic gestures as “Corrections” — repetition, reflexivity and a deliberate allergy to metaphor and ornamental language — to refocus the feeling of loss from physical death to the intellectual and spiritual depletion of selfhood and solidarity experienced by Black people almost everywhere, even in predominantly Black societies:

My friend

in Africa has a cleaning lady. They are both Black.

He tidies up a little before she arrives. Not too

much. Not to repeat myself. They are both Black.

Just a little. Because. Shall I go on?

By performing the struggle to speak in spite of this unsayability, “Hair is Choking the Drain” vocalizes the othering of Black folks in a markedly Eurocentric global culture, acting out a personal answer to the question posed by W. E. B. Du Bois in one of Williams’ epigraphs: “How does it feel to be a problem?”

Williams’ delicate and daring transitions between subjective and societal experience are exemplified in “Why does everything have to be about race with you people?” — a poem whose title signifies a racial underpinning that is nonetheless never explicitly mentioned in its body. Ostensibly, the piece is a first-person account of its speaker’s inability to identify with William Carlos Williams’ canonical poem “This Is Just to Say.” However, the reasons why that identification is impossible become increasingly clouded by: the speaker’s indecision (“it’s hard to parse who you are / from who you ought to be to parse your creole / from the queen”); the hand-drawn interlinear notations and substitutions that populate the poem; and, finally, ambiguity over the exact grammatical referent of “you.” The result is a subtle and multifaceted exposition of the internal and external obstacles Black folks face when trying to integrate race into the breadth of their experience.

The first half of Word Problems is peppered with references to Black subjectivity, incorporating racial awareness into a kind of tossed salad of affect. In contrast, the book’s second section cements Blackness as the central theme of many of its poems. In the above-mentioned entries, this shift highlights the role of anti-Black racism in conditioning the psychic landscapes explored earlier in the book. Elsewhere, like in the four-part prose poem “Where are you really from,” Williams presents insightful, matter-of-fact illustrations of the kinds of microaggressions regularly encountered by Black people in white supremacist societies. Still elsewhere, in poems like “The past sometimes appears conditional” and the concrete poem “Our eyes meet across yet another room,” Williams further departs from the eccentric, highly personal perspectives developed in his first section to instead foreground more objective overviews of Black folks’ circumstances in North America.

For me, it is these latter poems that present some of Word Problems’ biggest critical and interpretive challenges. “The past sometimes appears conditional” hits a profound and urgent note in its coupling of police brutality with the over-surveillance of Black bodies in general — for example, “He would get chokeheld / for wearing a hat in the hallway” — yet its assertiveness seems at odds with the hesitancy displayed by most of the book’s speakers, for whom self-doubt, disorientation and the lack of a definitive understanding are central aspects of Black experience. Similarly, “Our eyes meet across yet another room” presents a brilliant summary of a typical Person of Colour’s experience in white-dominated fields, but its reliance on concrete poetry’s conventional strategies of minimalism and punning feels formulaic in a way that much of Word Problems resists. In some instances, these approaches risk transforming the fundamental subjective dilemmas Williams highlights so brilliantly into mere setbacks on the way to a more objective awareness of Blackness — as if the “problems” of the collection’s title were not foundational or existential problems (which I tend to believe Williams is more interested in), but problems simply to be solved.

Admittedly, I cannot meet Word Problems’ evaluation of Blackness on even ground; as a white reviewer, my grasp of what Blackness means beyond our shared language is inherently disjointed from Williams’. Nonetheless, Williams’ work as a whole sits far from any identity politics premised on essentialism or exclusivity. Rather, Williams’ poetry is deeply influenced by — or alternatively inspired by and set against — the ever-deferred promise of a language that could speak to everyone. His dramatizations of the breaking of that promise both throughout our society and in our own self-judgements offer boundless opportunities for re-evaluation and change.