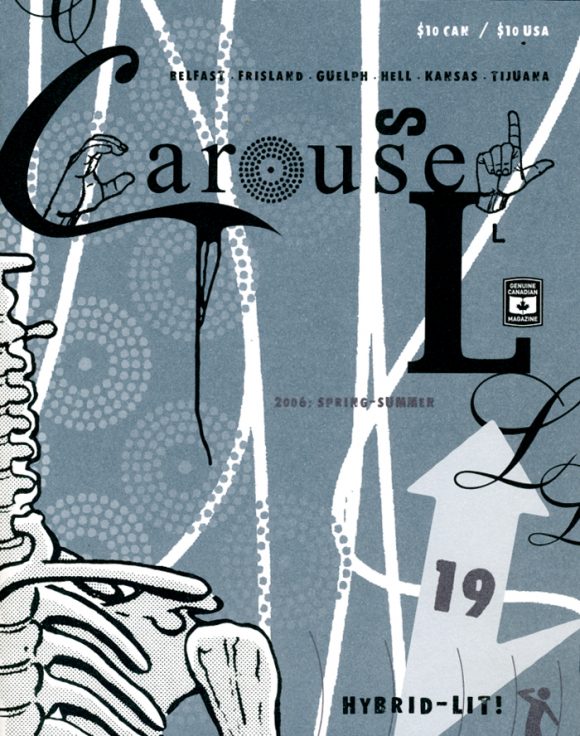

From the Archive: Emily Schultz (CAROUSEL 19)

EMILY SCHULTZ

Level 2: Frogger

(excerpt from Joyland)

Illustration by NATE POWELL

PLAYER 1

After Joyland closed, the youth of South Wakefield had nothing to do but concoct ways to kill each other.

Tammy sent home long ago, J.P. and Chris sprawled on the curb opposite the arcade, leaning back on their hands, drinking grape pop. Over the course of the night, the misplaced patch of boys grew in the stretch of cement in front of the Twiss’ Gas ’n Go. In addition to Christopher Lane and John Paul Breton, gathered a standard post-Indian-Creek-Grammar-School group: David White, Kenny Keele, and Dean and Rueben Easter. Pinky Goodlowe had been too steamed to stay. He’d jumped on his BMX and ridden away, massive knees hitting the handlebars.

“Man! I dunno, we got this sort of, like, bottomless summer now. Eight whole weeks of nothin’. How many days of pure street hockey d’you think you can stand? In a row, I mean?” J.P. spoke specifically to Chris, the others oblivious to the gravity of the situation. Chuckling, David had pressed his crotch against a gas hose, pretending to pump the pump. Between his legs the nozzle hooked in — blank tin body and glass face — the machine reduced to the simplest notion of female, something entered.

Chris shook his head. “The crescent’s good for it, I guess.”

“Yeah, but my folks hate it. They’ll beat my ass.” J.P. stretched his legs out in front of him, bent slightly at the knees. “Straight days of hockey, draggin’ the freakin’ nets back and forth every time a car wants in or out. The neighbours’ll be over yellin’ at my mom before the week’s out. What else we got?”

“I don’t know,” Chris tilted his head back and let the last swig of pop ripple through his throat. “Swim, bike, TV, soccer, baseball, the usual…”

“Pffft. Boring, bo-ring.” J.P. squeezed his bicep, the muscle bulging up around a mosquito that had landed there. He watched its back end fill with blood. When it burst, J.P. wiped the residue off with two fingers and leaned over to rub them on Chris, who lurched up and away a few feet. J.P. reached round and rubbed them on the ass of his shorts.

“I don’t know why you do that. You still get the bite, ya know.” Chris scrambled back down, settled on the curb more upright.

“’Sfun.” J.P. shrugged.

David dropped to the curb beside them, followed closely by Kenny, Dean, and Rueben. Behind them Johnny Davis had claimed a seat atop the mailbox in mute sixteen-year-old oblivion, with the exception of the odd fartish exhalation.

The side door to Joyland opened, rapping across the concrete night. They all stilled, watched Mrs. Rankin reach up to unhook the bells. In one hand she grasped the chip carousel from the counter, yellow plastic pouches still hanging from it. The other fist fumbled with the string of chimes — which warbled through the dusk with ecclesiastical melancholy — until Mr. Rankin appeared, a thick ring of keys hanging from his thumb. He reached up — the woman’s stubby white fingers still groping — and unjangled the bells with a click into his silent hand, the other closing the door and poking the lock.

They waddled to their truck to stash their things. She got in, sat staring out the windshield at the boys across St. Lawrence Street. She had trout-coloured eyes, visible even from that distance. Mr. Rankin returned to the door and fastened a heavy chain across its handle.

The boys sat with the final snap of the padlock clamping down on them. Mr. Rankin turned his back to the blotted black building and walked slowly to the vehicle, opened the door and got in — no sudden movements — as if he could feel bullets in the boys’ gaze. The potato chip rack, shoved between them in the front seat, waved little cellophane wings, rotating when the truck reversed. A scatter of gravel. But before the headlights had disappeared down the highway the boys had begun a eulogy, recounting their greatest Joyland moments.

Now there were a handful of players without games: a circle of smart-mouthed friends and a few clumsily told stories. Johnny kept lighting one cigarette off another and not saying a word. He stared at the building as if he was telekinetic, could tear the chains from the door with his eyes.

“What are we gonna do?” Kenny Keele snivelled. He bobbed his bowl-like feathered haircut. Chris glared at it, though Kenny’s small hawkish face was turned in the other direction. It was about the fiftieth time the question had been voiced in an hour.

“I don’t know about you,” David White said, “but I’m gonna lie in the middle of the road. Over my dead body can they close this arcade. I mean, what the fuck? We can’t play at Circus Berzerk, it’s in a mall! Our moms are there buying groceries and lottery and sweaters and shit. There are little kids climbing all over. You can’t even smoke there.” David flicked his cigarette across the gas station parking lot toward the closed booth. Chris eyed it warily. Red sparks flew up and disappeared.

David had a point. The only other arcade was lame. They had to walk into it through a huge open-mouthed clown face. There was a helium balloon stand in the front. The owner sold ball caps with fake turds on the brims under lettering that read Shithead, not to mention squirting flowers, joke birthday candles, sparklers. In Chris’s estimation, whoopee cushions were all right, but not when his best friend’s dad was there buying them.

David stood up. He removed his John Deere cap, his Playboy necklace, his digital watch. He dropped the chain and the watch inside the cap and handed it ceremoniously to Kenny.

“I’ll take that belt buckle off ya,” Dean said. It was as huge as a Harley, equally eagled.

“If I die,” David said, a sudden Southern twang to his voice, “give my mama my love.”

“What about Cindy Hambly?” J.P. snickered, half under his breath. Everyone knew she’d made out with David once, but was dating a high school guy now.

Kenny blinked behind his glasses, and accepted the cap and its contents with a constipated expression that Chris recognized as alarmed devotion, vintage Keele.

David stalked to the centre of the road and crouched down, spread-eagle across the centre line, legs waiting for northbound traffic, head and arms waiting for southbound.

“Come on, White,” Chris yelled. “Don’t be such a martyr.”

David held up one hand, middle finger extended, no intention of moving.

“It’s a peaceful protest,” Kenny insisted, and the next thing Chris knew Kenny had spread himself across the northbound lanes, the John Deere cap carefully folded and clutched atop his chest.

“What the hell,” J.P. said, and left Chris sitting on the curb.

The Easter brothers followed J.P. out, Dean first. Rueben rolled to the pavement after him, propping his head up on his brother’s shins.

Across the street, Joyland glared morosely. The reflection of one streetlight caught in the small high window. Chris had a feeling somewhere inside, coiled like some long sticky thing waiting to snap loose.

“Come on, Lane, show your love,” J.P. yelled.

Chris glanced up at Johnny Davis, Video Game God. He didn’t even bother looking down at them, just stared into the dead-eyed windows of Joyland. The circle at the end of his cigarette glowed orange, made a small perfect hole in the night.

Chris crawled on his hands and knees. Under his palms, the concrete had tiny gritty teeth that left marks in his skin. Rolling slowly onto his back, he lay in the middle of a lane looking up. Waiting.

Gazing up into the night, he willed himself into a different headspace, a time before Joyland, and a time ahead. Suddenly Chris knew why all the sci-fi series were about searching for a half-extinct human race and trying to get home. He was trying to formulate a theory, distill it from his brain, and put it into words — when Johnny Davis jumped off the mailbox.

“What is this?” Johnny yelled as if he had just noticed what they were doing. “It’s like you’re playing chicken without cars. Kid shit,” he said. He turned, kicked the mailbox three times hard. Chris raised up on one elbow, watched Johnny lurch all ninety-five pounds into it, the slim tendons in his forearms popping as he rocked the red metal off its legs. In slow-motion the box tipped, then landed on its back, the arrow-like Canadian Postal emblem pointing suddenly skyward. The sound thundered across the gas station parking lot and echoed on the empty highway. Chris could almost feel the vibrations jolt through him.

The boys in the street sat up on their asses, stared. No one said a word.

Johnny Davis plunged his hands deep in his pockets and walked away slowly, looking nothing like a guy who’d just lost it.

David snorted, and Kenny lay back down, the rubber grip of his running shoe facing Chris. A red bulls-eye of rubber.

Chris turned and watched Johnny Davis trek the entire length of St. Lawrence Street. From a distance Chris knew they must look like they’d parachuted out of the dark and landed there — arms and legs thrust out haphazardly across the cement, sneakers pointing at the heavens. But Johnny Davis did not glance back. He walked the four blocks up and when he reached the fork in the road where the downtown intersection began, he veered left and passed from sight. It must have taken at least ten minutes. Still, not one set of headlights.

Chris paused another minute, looking up at the sky, willing something to happen.

Nothing did.

Level 2: Frogger (excerpt from Joyland)

appeared in CAROUSEL 19 (2006) — buy it here