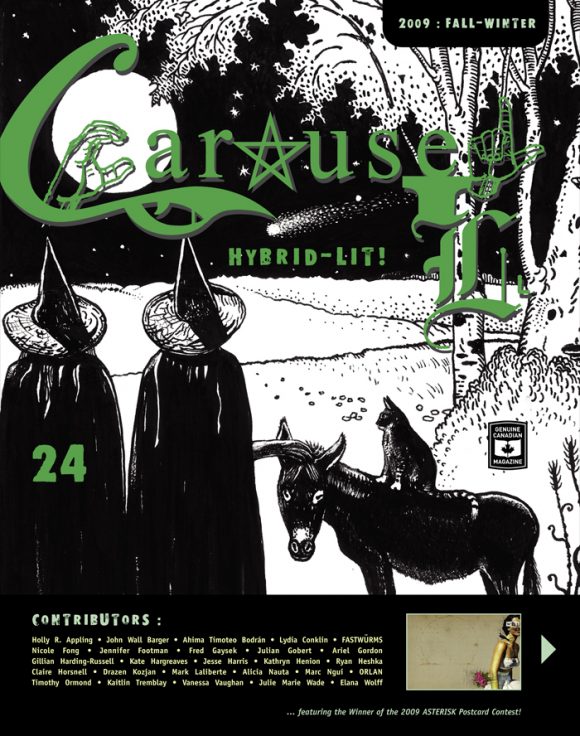

From the Archive: ORLAN ‘Long Live Transitional Flesh’ Interview (CAROUSEL 24)

Given French performance artist ORLAN’s dedication to altering her physical appearance in the name of challenging the limits of human physicality, it’s ironic that her rather idiosyncratic look — the Bride of Frankenstein-esque hair, the exotic implants on her forehead and the owl-like glasses she often wears — makes her instantly recognizable in a way that few artists since Andy Warhol have been able to manage.

In a world fascinated by cosmetic surgery, where the pursuit of health and the perfection of the body have become a new kind of religion, her collected body of work still manages to present a ferocious challenge to the idea of bodily unity and integrity. In her work, ORLAN combines elements of religion, pornography, horror and comedy — all in the interest of investigating interiority, and interrogating the moral and physical codes of acceptance for the human body. In many ways, through her work, ORLAN has become an ideal poster child for the late twentieth century’s conceptually expansive posthuman movement.

Posthumanism — in an oversimplified nutshell, the idea that humans are beings with fluid, shifting identities that are defined primarily by context, rather than beings in possession of an essential nature — began to gain ground as a philosophical position within the culture in the late 80s and early 90s. Steve Nichols published the Post-Human Manifesto in 1988, and, a few years later, Donna Haraway’s much-cited essay A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century outlined ways in which critical theorists could move beyond binaries and boundaries relating to flesh and gender. The barriers between what was ‘human’ and what was ‘artificial’ began to be called into question, and the idea that flesh is a morphing entity began to take hold; this point of view necessarily undermines many of the concepts with which we as humans commonly define ourselves, particularly in terms of gender — and indeed, in synch with the times, ORLAN famously described herself as “the first woman-to-woman transsexual.”

In the early 1990s, as cultural theorists and critics became increasingly fascinated with posthuman and cyborg theories, ORLAN produced her most notorious performances — a series of orchestrated surgical operations accompanied by her landmark Carnal Art Manifesto — that turned her into the embodiment of morphing flesh. This, of course, was before cosmetic surgery went completely mainstream — before supermarket tabloids ran monthly “who’s-had-what-done” headlines — and she consequentially became an icon in both the art world and the larger pop cultural sphere, a misunderstood and often misrepresented fringe celebrity. Controversial Canadian auteur David Cronenberg, a director also notable for his fascination with the fluid division between what is human and what is not, even wrote Painkillers — an original script for a thriller set in an alternate world in which sex has been replaced by public surgeries — based loosely on the ideas contained in her “Carnal Art Manifesto”. ORLAN and Cronenberg later met in person at the 2003 Cannes Film Festival, and there were rumours that the director had even offered her a small role in the film; since then, however, it seems that Cronenberg has opted to shelve the project indefinitely.

Although ORLAN is most well known for her epic operation-performances, she has made a lengthy artistic career out of investigating the liminal aspects of her body. ORLAN’s work has transformed her living flesh alternatively into the contents of a reliquary, the means by which the man-made construction of the city is measured, and the canvas on which the Western ideals of beauty are both constructed and deconstructed. The body, in her work, is both subject and object; permanent and ephemeral; mortal in itself and made immortal through the ever-shifting progression of technology.

In the twenty-first century, however, the text with which ORLAN is working has shifted from the body itself to the image of the body: an image increasingly subject not only to an external code of acceptability but also to the subjectivity of digital manipulation. In her ongoing work Self-Hybridizations, ORLAN merges her own image with ancient, non-Western images of the human face — and her choice of pre-Columbian, Native American and African sources has, as ever, been controversial. In these works, she investigates conventional standards of beauty by altering her own image to conform to other long-standing — if unconventional — beauty paradigms. By consciously shifting the boundaries between what is considered beautiful and what is considered monstrous, ORLAN examines human fears and aspirations related to the flesh without sacralising its mortification. Her fantasies of transforming the human body both confront and expose the standards by which it is repeatedly judged and, invariably, found wanting.

Interview conducted March, 2009

ORLAN, how did you reconcile the violence implicit in your surgical performances with the need to undercut the “prestige of pain” and suffering?

My artwork is precisely against pain. As I said in my manifesto, “Carnal Art finds the acceptance of the agony of childbirth to be anachronistic and ridiculous. Like Artaud, it rejects the mercy of God. Henceforth we shall have epidurals, local anaesthetics and multiple analgesics! Hurray for morphine! Down with pain! Vive la morphine! A bas la douleur!”

In my surgical operation-performances, I decided to use the literalness of the performance to express the violence done to the body, especially to women’s bodies. The Christian religion rejects the body, especially the pleasure-body. When it pays attention to the body, it is to torture it, to cut it, to make it bleed. Christianity proposes a guilt-body, a body that must suffer to atone. My first deal with the surgeon was no pain, neither during, nor after. My work is related to pleasure and sensuality; I do not consider pain to be a form of redemption or purification.

In the context of the posthuman, to what extent is gender still relevant as a site of resistance/protest?

It depends on what one says and how it is said. All my life I have tried to break up the barriers between generations, skin colours, gender, and in particular, between art fields; barriers that are not always easily seen. For me, I consider myself both a man and a woman — “une homme et un femme.”

How has the politics of viewing the body changed in recent years?

Since Vesalius (1514–1564), bodies have been opened. There is a history of medical imagery and currently we are in the time of genetic manipulation. All technological innovation relating to the body make this evolve — in particular due to the work of artists using biotechnologies that question the essence of the body. Currently I am developing an installation entitled The Harlequin Coat, created from living cells from people of various origins and animals.

In the 90s there were rumours that you were going to have the largest nose that your face could support surgically constructed; was this true, and if so, why did you decide against it?

My surgical operations caused many rumours, including that I had 164 operations. The newspapers harmed my work very much, making it seem as if surgical operations were my entire life! I think that my work is very complex, but that it is also very easy to reduce to headlines of scandal newspapers. For most artists it is the same thing: one stops on a work or on an image and the depth of the entire work is ignored. It needs distance and analysis, and not everyone is able to handle that. The ignorance affects mostly my surgical operations, which actually scared people. But there were moments of my artist-life that were different; I am a normal artist when I am not in an operation room. The aesthetic surgery is not my entire practice, I only attempted it from 1990 to 1993! People usually accuse me of being very narcissistic, an exhibitionist, but they don’t say that to others! I also believe this criticism is very specific to the visual arts field. When someone tries to show something else from what it could be, detractors say that it is too narcissistic or too exhibitionist. But when some popular singers play with their body in front of their public, give a climax in front of 20,000 spectators, no one will say it is narcissistic, exhibitionist or disgusting. It is really a rigid way of seeing things. The starting point used by the artist does not matter, what really matters is what is produced, and if that brings something interesting.

Is the distortion of the image of the body simply a manifestation of establishment (media, capitalist) strategy, or does it shift the viewed body into the category of the posthuman?

If the distortion of the body is actually done, it is not posthuman. However, the artist can offer new images to oppose — to question — this distortion of the body.

I play on my presence and my representation, even attempting to unsubscribe from tradition, in order to challenge a society that designates the models we should integrate, be they those of art history, of magazines, of advertising, the woman we should be, the art we should produce, the thoughts we should think. This is of course, merely an attempt at de-formatting: it is difficult to produce external images, but one can at least counterattack with images, creating responses that counterbalance the data scales and initiate debate, feminist debate, among others.

Why the shift in your work from remaking the body to remaking the image?

Changing my body was for me a way to change my image — to make new images using new technologies.

My series of surgical performances has two titles: the first, The Reincarnation of SAINT ORLAN, was chosen to do away with the fiction of a saint called ORLAN, and the word reincarnation was chosen in opposition to resurrection; in 553, the Council of Constantinople condemned reincarnation, especially because there was a preference for reincarnation over paradise. The second title is Images New Images, as this series of surgical operation-performances was designed to refigure my face, and thus to create a new image for myself that would itself produce new images, creating a kind of sfumato between presentation and representation.

What is important for me is to turn around possible images, to make them go out, to push them out, always surprised at the vision of what we could be and the essence of beings.

If we are all posthuman now, how are we to connect (especially being fraught with physical imperfection)?

Physical imperfections exist according to models. Cronenberg says that “[t]he first fact of human existence is the body. The further we move away from it, the further we move away from the human being. Technology is no more of a danger to us than we are to ourselves, since it emanates from us.”

If the body is the text — or if the body as image is text — how is this affected by mortality? What are your plans for your body after death?

I will not give my body to the science, but to a museum. My body will be in the centre of a multimedia installation.

Special thanks to OCAD’s Intermedia Department for providing CAROUSEL with a connection to ORLAN; and to ORLAN’s assistant, Anne-Sophie Garcia, for helping with the translation of this interview.

Long Live Transitional Flesh

(with several bonus sidebars)

appeared in CAROUSEL 24 (2009) — buy it here