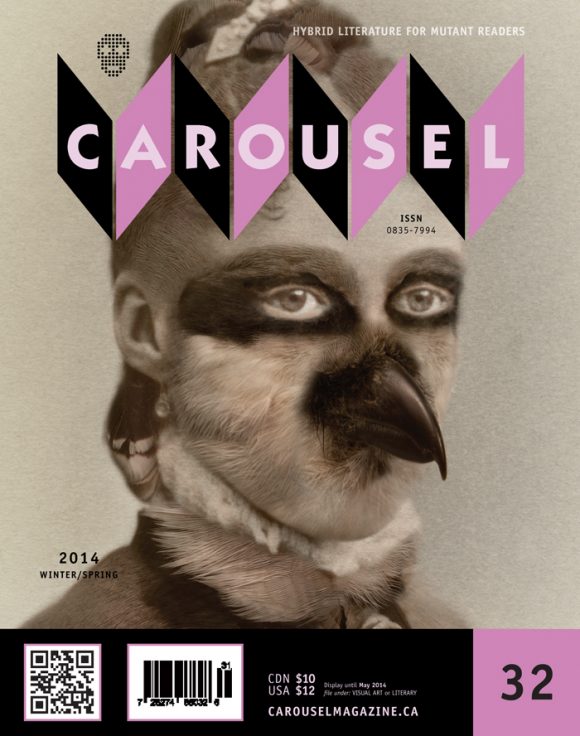

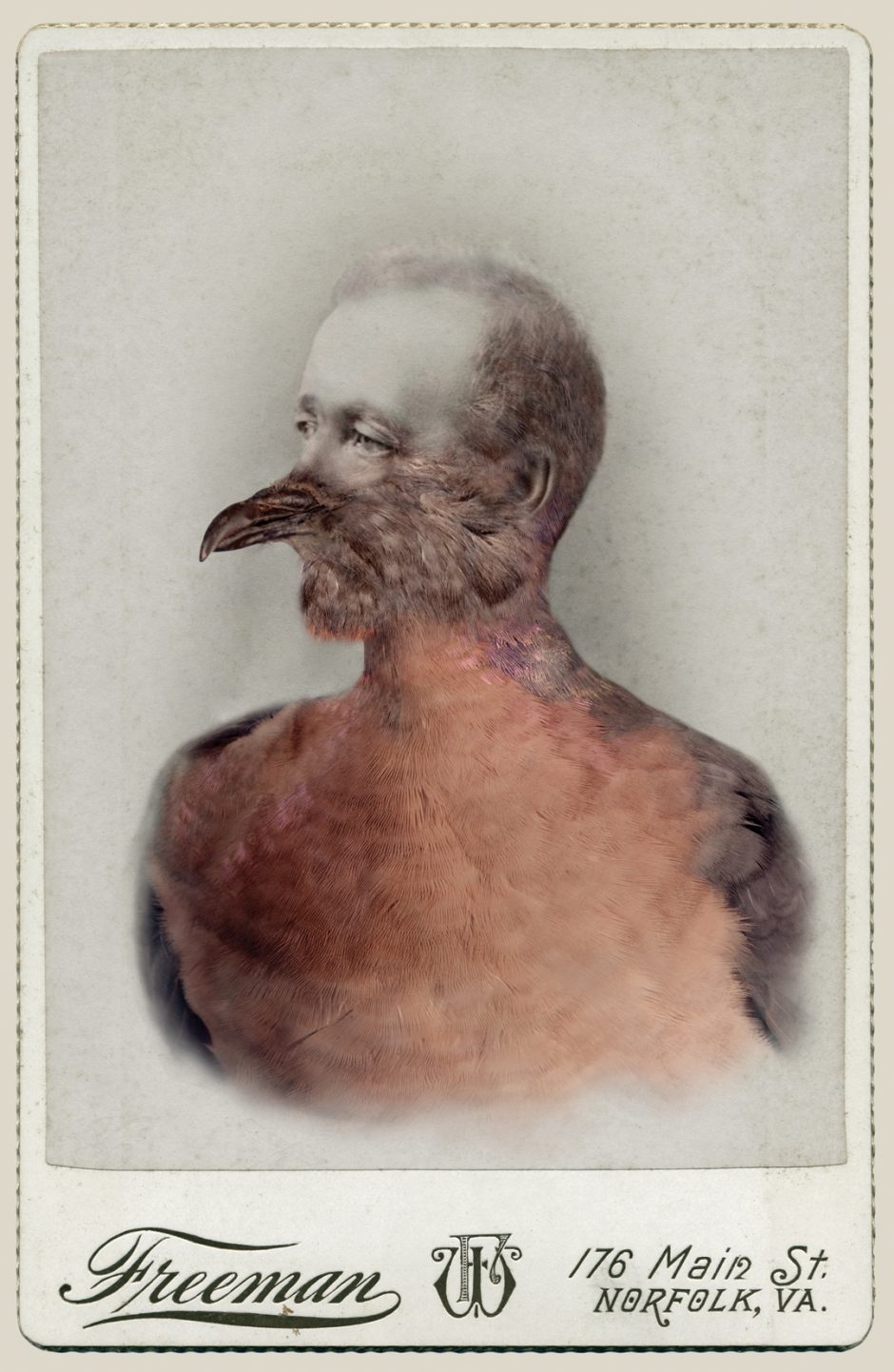

From the Archive: Sara Angelucci ‘Aviary’ (CAROUSEL 32)

C-print, 22 x 33.5 inches — 2013

Extinction. Such an outrageous word, and made common thanks to that Darwin fellow and his incredible theories. The word has the connotation of chances irrevocably gone. But the utter demise of the pigeons is an impossibility. Not even man could destroy such a quantity. Nothing has an utter end — not the pigeons, and certainly not the human soul, which continues on and ever on.

— Claire Mulligan, The Dark (2013)

There was a time when massive flocks of passenger pigeons would habitually darken the sky, literally taking flight by the thousands. Looking something like a cross between the common pigeon and the mourning dove, they were extensively hunted for food and sport, leading to a steep population decline during the Victorian era in North America. Scientists voiced concern about the animal’s future at that time, but it seemed to contradict the visual evidence of these still-pervasive birds. Warnings went unheeded, sport and habitat destruction continued, and the last passenger pigeon died in the Cincinnati Zoo not long thereafter, in 1914.

C-print, 22 x 33.5 inches — 2013

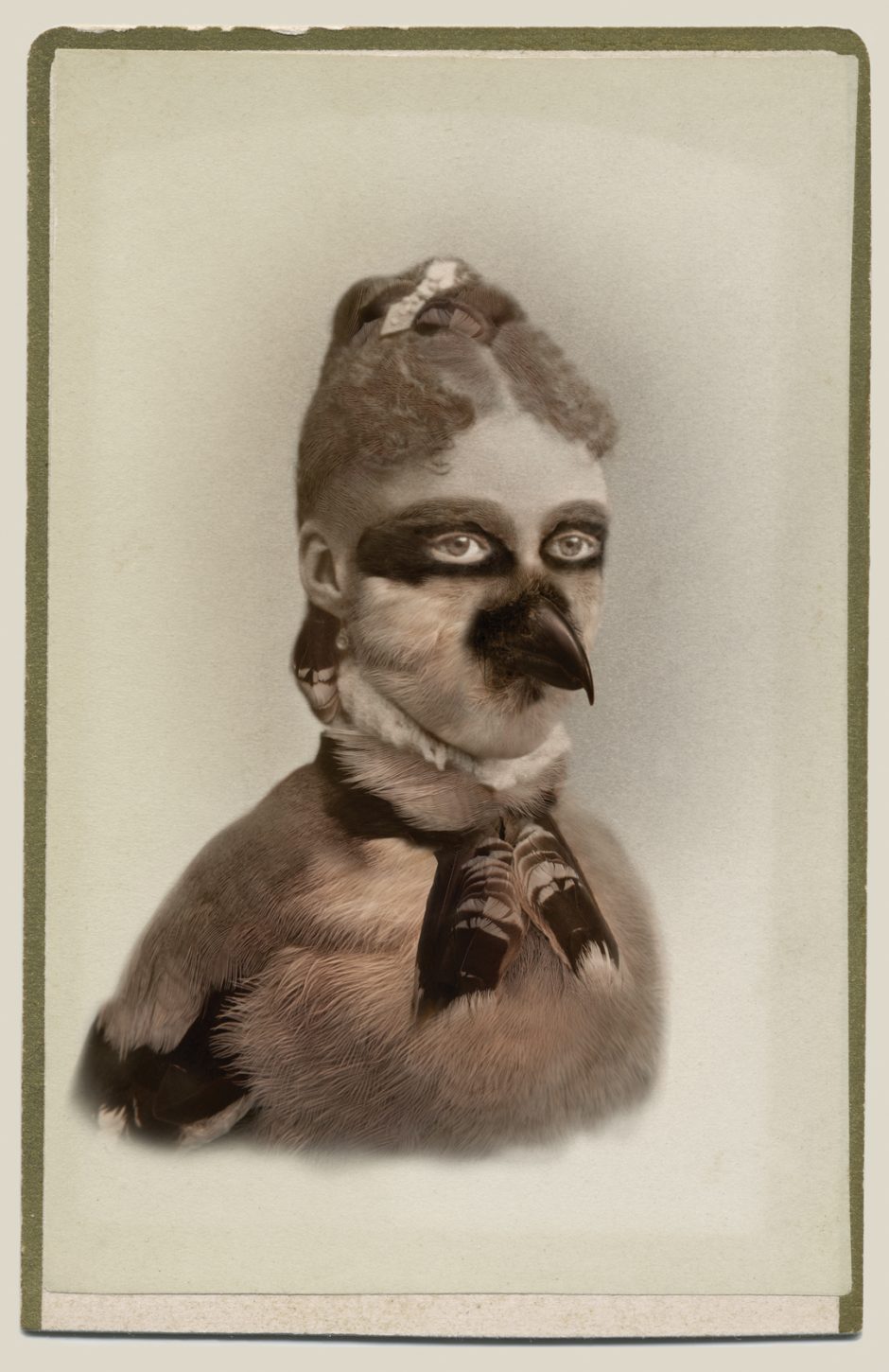

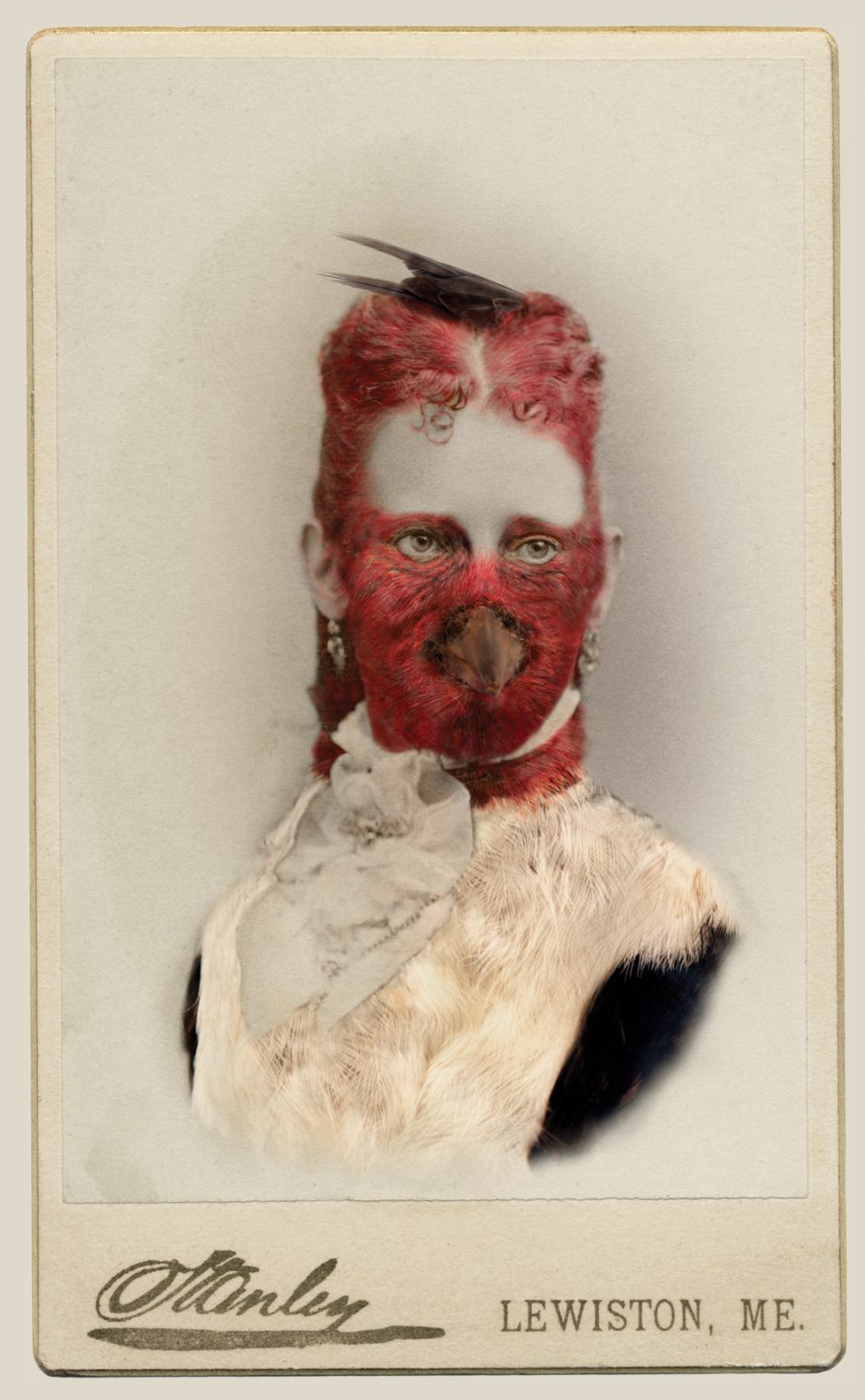

The passenger pigeon is one of several extinct or endangered North American species forming the foundation of Sara Angelucci’s Aviary series. Each “portrait” is a curious amalgamation of a found Victorian era carte-de-visite (a wallet-sized albumen portrait print mounted on cardstock) and a bird specimen photographed from the ornithology collection of the Royal Ontario Museum. Each resulting image evokes a layered picture of a time when portrait photographs were cherished heirlooms, curiosity collections were a popular pursuit, and birds were widely hunted or obtained as pets. All connect to Victorian America, when everything from Darwinism to Spiritualism held popular attention and debate. And while these associations are all quite firmly rooted in the past, Angelucci’s hybrid creations of animal and human somehow pull history into the present, bringing it back to life.

Angelucci has clearly articulated the connections between these histories and her images. But, of all of them, her mention of Spiritualism is perhaps the most complex, and least direct, association. An intriguing account of the movement can be found The Dark, a historical fiction set in the same period that these portraits were taken. The novel, coincidentally published around the same time that Angelucci’s portraits were first shown (at the Art Gallery of York University in the Spring of 2013), tells of the Fox sisters of New York, who were credited with originating the Spiritualist Movement in North America. It traces their struggle with authenticity and swaying popular opinion. As the narrative unfolds, it also paints a picture of life in Victorian America, and one can almost imagine Angelucci’s photographs somehow falling into the story, so strangely do the connections seem to fit into place. Curiously enough, birds figure throughout the novel, the passenger pigeon in particular. The eldest sister Leah, for instance, owns a large aviary in her home, and was attacked by a flock of passenger pigeons as a child. Birds are used here as a metaphor for souls and spirits, and while not an uncommon usage in fiction in itself, the link to Angelucci’s bird portraits is uncanny and reveals just how in tune her images are with the tenor of the times.

C-print, 26 x 38 inches — 2013

Spiritualists claim the ability to raise the dead, and act as mediums for communication with them. What is compelling about author Claire Mulligan’s perspective on the movement in The Dark is that readers are left to decide how much of the Fox sisters’ performance was artifice and how much was gifted ability. Their talents were debunked, even by the sisters themselves, and yet people continued to believe. Likewise, what’s peculiar about the Aviary portraits is that even when the backstory is exposed, after the artifice is revealed, the portraits still hold believability.

Angelucci is not averse to showing the original cartes-de-visite when exhibiting the Aviary series, welcoming viewers to access her source material. Even without this access, in this age of Photoshop manipulation, it is not difficult to ascertain that these are portraits created through some sort of digital assemblage. But this is somehow so easy to ignore when viewing the final photographs. A viewer might spend a bit of time marveling over the line they can’t quite find between the two source images, but really, one spends much more time reading the image not as a hybrid, but as a portrait in its own rite. These images live and breathe a certain kind of magic. They have that strange/familiar quality that lends them an uncanny aspect. They pull the viewer in each time, but not without hesitation.

C-print, 22 x 33.5 inches — 2013

The potential narrative behind these portraits is compelling — each one surely has a rich tale to tell. The portraits cannot speak, of course, leading us to form our own impressions of their lives during that period. Who were these people, before Angelucci transformed them into their present state of existence? Did they partake in the popular past times of the day, trading their carte-de-visite with other friends and relatives? Did they enjoy the novelty and curiosity acts that passed through town? Some might draw a connection between these bird/human creatures and the “human curiosities” that travelled in circuses. At one point in The Dark, the Fox sisters meet P.T. Barnum and encounter “Yan Zoo the Chinese juggler. Zip the Pinhead. The Mammoth Highland Boys, fat as barrels in their kilts. Mr. Dilwali the Snake Charmer. A Circassian Beauty caped in her wild black hair.” But the Aviary portraits seem to actively negate such associations. They invite neither gawking nor jesting. Despite the significant alterations they’ve undergone, they still contain all the dignity and poise of the original cartes-de-visite. In each case, the eyes remain unchanged, and they hold the entire image together. Their gazes, although never confrontational, compel us to view them as noble beings. They own their images.

Something transformative also happens when the series is viewed as a whole. Each hybrid Angelucci creates is unique, both in terms of the originating image and the choice of paired bird. Yet seen together, they are no longer individual images, but a collection. An aviary is, after all, a large cage for housing a collection of birds. These anonymous cartes-de-visite, raised from the virtual space of eBay, depict people that are completely unconnected, except for their shared historical period. If any were related, or knew each other, it is only by coincidence. But in Angelucci’s gathering and transformation, they gain a new sense of connection and wholeness. They continue on and ever on.

Sara Angelucci: Aviary

appeared in CAROUSEL 32 (2014) — buy it here