From the Archive: Aaron S. Moran ‘The Rebuilder’ Interview (CAROUSEL 32)

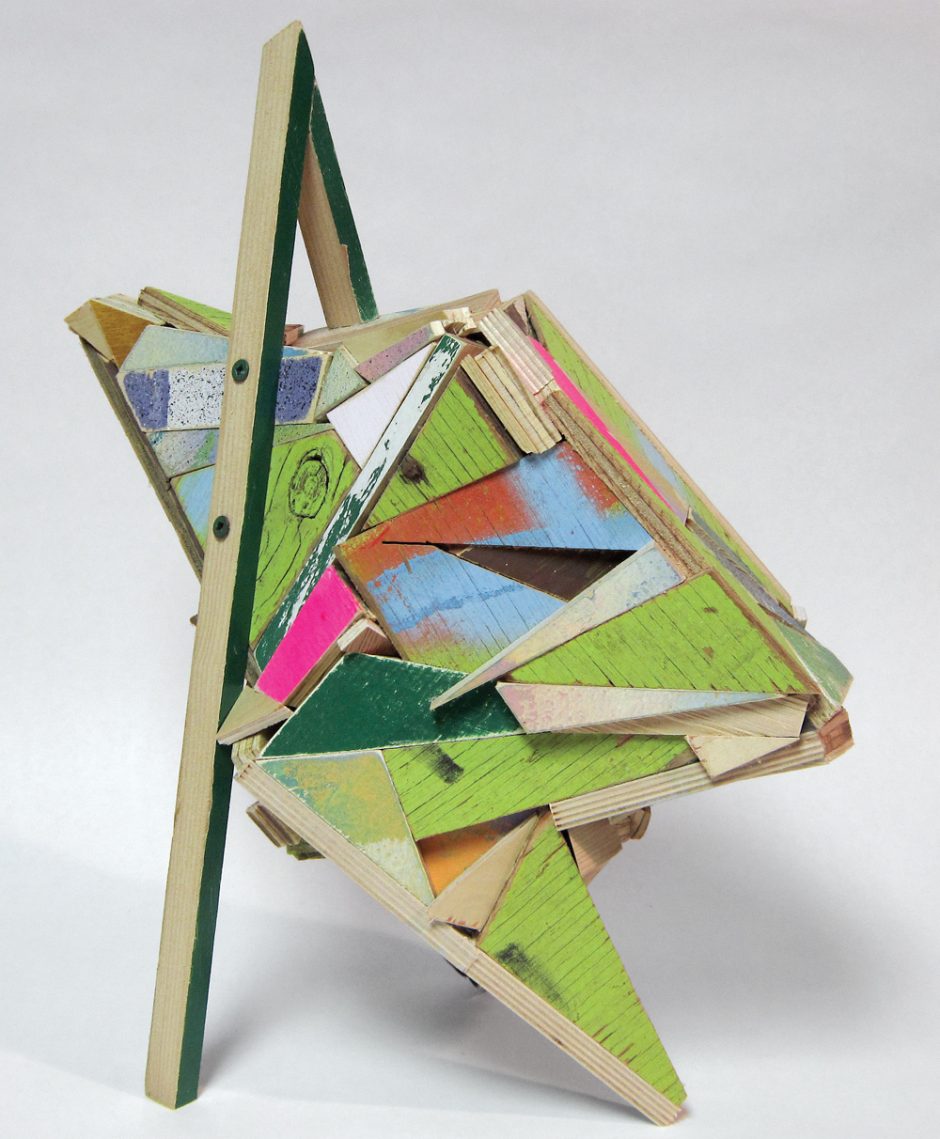

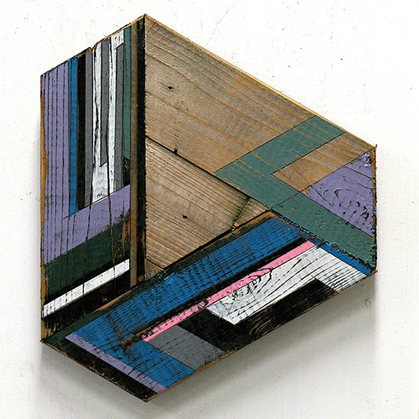

Through his multi-dimensional assemblages, artist Aaron S. Moran attempts to represent the rapidly changing context of Langley, British Columbia — his once rural hometown, now a growing community 50km east of Vancouver. For Moran, this setting is foundational to his practice and is the primary source for gathering inspiration, ideas and materials for his chosen medium. He amalgamates and re-appropriates bits and pieces of intermediary sites that have been left abandoned by developers. Through collagist methods, Moran creates his constructs from useless materials that he unearths during his ‘nature’ walks through the flattened fields where the forests and old neighbourhoods of Langley previously stood; he only uses what he can carry back to his studio.

Interview conducted August, 2013

How would you best describe your sculptural work in a straightforward, ‘tombstone-esque’ sentence?

They are a collection of materials reorganized into objects that draw attention to the materials and practices of development I see happening around me.

The decisions you make when choosing materials in your studio remind me of watching a child playing with blocks. Is there indeed a playful quality to your artistic process?

I make art because I literally find it fun to do so. One of the first things I loved doing when I was in kindergarten was use those flat blocks to make patterns. Yellow hectagon, red triangle: I remember the way they interlocked with each other. Basically when I work now as an adult, I cut up the random pieces I have collected and it’s satisfying to have those pieces click together perfectly, with little planning.

Is it fair to say that appropriation impacts your work?

I’m not appropriating the idea of material, I appropriate the materials themselves; the final pieces I create are far removed from the source material’s original intentions. Instead, I would say that the work

re-contextualizes the site from where they are from. I think of them as placeholders for a location; I take things that are discarded on the ground and make something out of them that represents where they came from. They act as a monument to a location.

So the majority of your pieces are composed from areas around you, like Langley and Surrey?

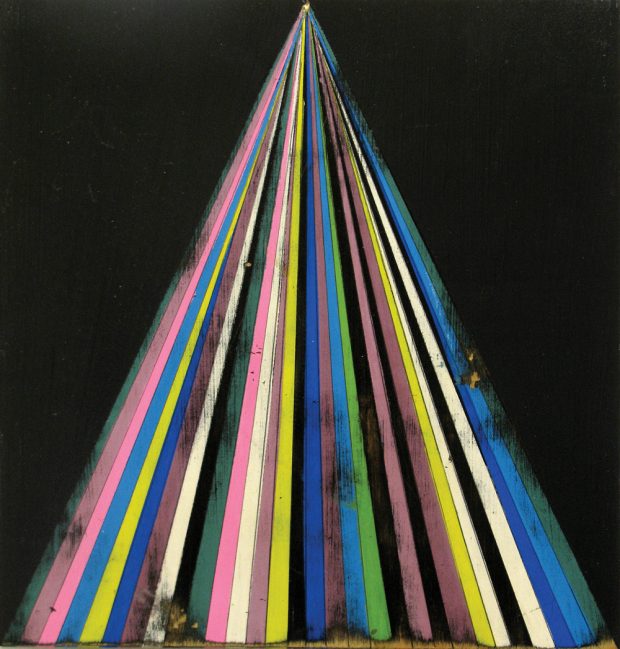

I currently live in Surrey but my studio is in Langley. 138 (Broken Triangle), 2013, one of the more recent series I made, contains material from Surrey. Surrey is a little more urban, while Langley is more rural. Both communities are being developed. Everything is moving east from Vancouver, so Surrey is starting to build skyscrapers, while Langley is getting row after row of townhouses. Every field, forest, single lot home is basically developed into a low-rise condo. I obviously understand that people need a place to live, especially with how expensive it is to live in Vancouver. But the problem I have is the way developers go about doing things. These new developments run like a cartoon background along the blocks, repeating the same structures where only the paint schemes differentiate one from the other. There’s nothing in-between but a strip mall that contains the same stores as the neighbouring strip mall. There’s just no character and no culture and everything is being replaced by monotony.

Do you feel your work reflects the setting’s transformation?

I definitely hope it comes through my sculptures. When I go to sites of development, there’s usually a jagged pile of junk left behind consisting of wood, metal, drywall, whatever. Basically just giant chunks of disorganized material piled up; in some cases, certain pieces actually match those shapes. I think that the sculptures I make from that particular material present a variety of structures and forms. I try to see how far I can push the material — how many different forms can be created over time, whereas developers have found a formula that places importance on speed and efficiency.

Since you do reclaim this discarded material from these chosen landscapes, would you consider yourself an earth artist?

No, I wouldn’t consider myself a land artist, directly. If I were to return the pieces back to where they came from then that would work. I hope that what I’m creating would be a primary source of where the material comes from.

Do environmental politics influence your motives?

Environmental issues definitely play a part. I love the aesthetic of the weathered, discarded material. It’s pleasant to look at and use. They are the kind of textures that you can’t emulate. Plus they are free and lying around. A current example being Wash Up (Boundary Bay), 2013, which was composed around a piece of plywood that was found washed up on the shore of a beach on Boundary Bay. It was a lime green painted board that had been weathered by the shore environment, giving it a wonderful patina. I’m not a hardcore environmentalist. I’m more into the natural environment of what’s around me. I’m probably most interested in development practices.

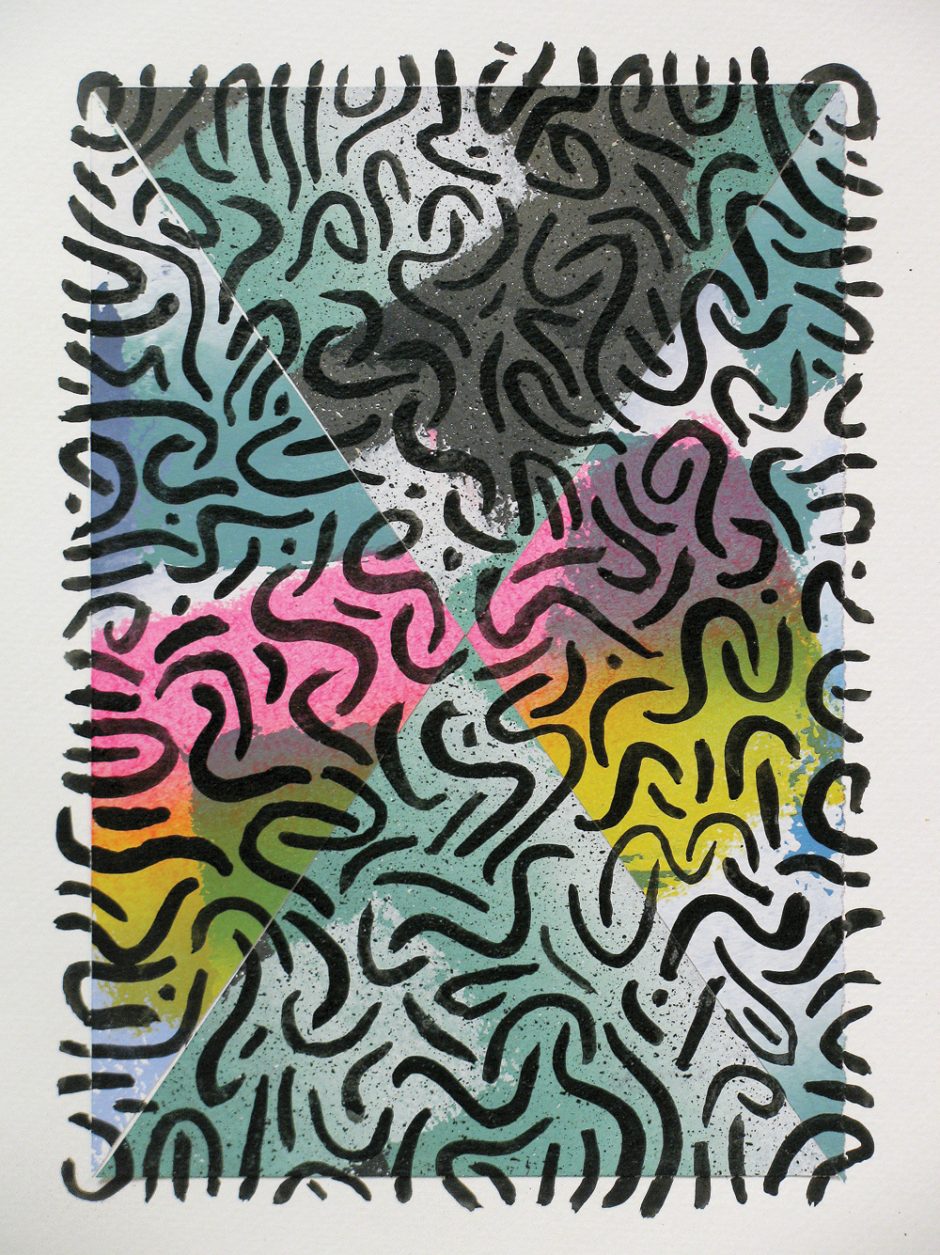

While the majority of your work is three-dimensional, you were recently invited to be part of an annual group exhibition that concentrated on the disciplinary of contemporary drawing, Drawing Expo 13. How did you come to be involved in the show and what did you create?

The curator came to one of my exhibits and asked if I wanted to be included. Since I regularly produce sculptural work, I thought it would be interesting to probe what I considered drawing. I created Imprint, 2013; it’s a sculpture that sits in front of a wall hanging, which are both painted white with a black line pattern throughout. The lines were drawn with India ink, cut-up and reassembled, which created a trippy, pattern-on-pattern aesthetic. I tried to come up with something that fit the two-dimensional theme, while retaining the essence of what I do.

Can you speak more about the two-dimensional side of your practice?

Although I enjoy creating things other than sculpture, I have a hard time justifying those pieces. So I create zines that act like personal archives; they are casual compilations of my sketchbooks and drawing, random ideas and doodles. My zines allow me to explore the ideas I am interested in and develop the aesthetic readers would recognize of me.

Your aesthetic is fluent — from your zines, through your drawings, to your dimensional constructions — particularly with your animated colour-palette and ’80s ‘pop shop’ application. Do these visual characteristics strike a chord with you artistically?

There’s definitely something I enjoy about that kind of work and artists like Keith Haring — specifically the looseness and causality of the line. I feel like I sometimes try to incorporate some of those experimental drawing styles into my sculptures and two-dimensional work.

Regarding my colour-palette, I’m just really interested in vibrant colours; I couldn’t say exactly why. I am making a shift, though, concerning my colour use: before, I would not do anything with the found wood, always leaving it as is; but now, I’ve started painting some pieces. I’m trying to incorporate my hand into the work, and the colours are a result of that. It’s my form of mark-making.

Aaron S. Moran: The Rebuilder

appeared in CAROUSEL 32 (2014) — buy it here