From the Archive: Daniel Arsham ‘Relics for the Future’ (CAROUSEL 34)

From generating performances with choreographer and media artist Jonah Bokaer, to designing sets for Merce Cunningham, to having your work curated by pop-star Pharrell Williams, collaborations are a major element of Daniel Arsham’s practice — one of the many facets of a career that has swiftly rose to international attention. He’s also part of Snarkitecture, a collaborative effort with Alex Mustonen, which blends art and architecture to create installations that attempt to “make architecture perform the unexpected.” But Arsham also has a solo artistic practice, one that maintains audience accessibility, but has its origins in a profoundly personal experience. The combination of these two qualities makes for work that has compelling visual aesthetics and haunting undertones.

In an Instagram caption on Daniel Arsham’s homepage, the artist writes about the pink fibreglass insulation that covered the walls and furniture in his home after Hurricane Andrew roared through it in 1992. The storm had left behind “perfectly formed pink ghost images of everything.” One can only imagine the impact in the mind of a young 12-year-old boy emerging from his hiding place to encounter such a scene. For him, it was the remains left by the storm — the shattered glass, the skeletal architecture, possessions strewn helter skelter — that have resonated most deeply, and have informed his artistic practice over the years.

Arsham, now based in Brooklyn, creates sculptures of everyday items cast in broken glass and volcanic ash, among other materials. The objects are haunting in their transformations, giving the sense of profound weight and substance, but also a certain frailty. This delicacy comes through the casting process, which involves a chemical reaction that creates a speedy, initial decay of the object, so that certain areas are immediately worn away to leave the impression of an artifact gradually worn away by time. And while the objects Arsham selects might seem ubiquitous and random at first glance, upon accumulated viewing it becomes clear that he’s gathering a particular typology. Basketballs, baseballs, laptops, a polaroid camera, a movie projector, an electric guitar, turntables, payphones, a tape deck — an iconography of contemporary culture takes shape, one that’s often near or past the edge of being obsolete. As a whole, they appear tethered to the recent past, even as specifically as the 1992 event that impacted Arsham so deeply.

As reproductions, the objects are rendered in white and shades of grey, suggestive of the physical ghostings that Arsham experienced post-hurricane. The material choices are crucial, all of which evoke the residue of geographical upheaval. His pyramid of cast baseballs, for instance, titled Baseball Gradient (2014) is composed of five different geological materials, including crystal and glacial rock dust.

While the link to Hurricane Andrew is relevant and revealing, it’s not essential to connecting with Arsham’s work. In an interview for the Guardian, Arsham said that he’s “taking the past and jumping over the present into the future.” It’s in the idea of adopting a futuristic gaze and imagining how modern culture might be witnessed, in its small surviving singularities, that his work lives. It interrupts a time trajectory, as though pulling time up and over itself. The sculptures’ monochromatic presentation erases some of their specificity, opening a door to re-witnessing them as objects open to interpretation. In this, Arsham’s work shares territory with speculative fiction, along the lines of Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy. Atwood’s vision of the future is not drastically different from the present, but feels like a natural progression, creating an unnerving sense of believability. In the first book of Atwood’s trilogy, Oryx and Crake, she writes: “‘When any civilization is dust and ashes,’ he said, ‘art is all that’s left over. Images, words, music. Imaginative structures. Meaning — human meaning, that is — is defined by them. You have to admit that.’” To step into Arsham’s world means being just on the edge of such a state, where objects are made of the remnants and ashes that still linger and reflect a seemingly random smattering of remains from a past civilization. The “art” is seen only from the other side, when you step back from the objects, and Arsham’s fiction. Atwood has summed up her perspective on the future by quoting fellow speculative fiction writer William Gibson: “The future’s already here but it’s unevenly distributed.” Time also takes a strange path in the wake of Arsham’s sculpture.

These objects — other examples include a Goodyear tire made from rose quartz, even a Shell gas sign made from obsidian — straddle a delicate balance between presence and absence, destruction and accumulation. Talking about Hurricane Andrew to Whitewall magazine, Arsham said that “after the storm there was glass everywhere. I went back to those memories and tried to find materials that I could repurpose. For me, it was about taking something that is broken, useless, and remaking it in a way that has a purpose about it, or can go back into a form that has intention.” His sculptures undergo a transformative act, one that moves ever-forward and adapts to a state of change. While natural disasters are devastating, as pure events they are also richly captivating. In his text, On the Importance of Natural Disasters in 1960, artist Walter De Maria describes their value:

Now just think of a flood, forest fire, tornado,

earth quake, typhoon, sand storm.

Think of the breaking of the ice jams. Crunch.

If all of the people who go to museums could just

feel an earthquake.

Not to mention the sky and the ocean.

But it is in the unpredictable disasters that the highest

forms are realized.

They are rare and we should be thankful for them.

And although it’s hard to say if De Maria would have spoken so highly of a hurricane if one had actually devastated his own home, even Arsham clearly recognizes the value of ruminating on natural disasters and considering their role in shaping existence. “When we think about nature’s impact in architecture, earthquakes, hurricanes, tornadoes, all of that, it’s often done in a very fast and violent way,” he said in Whitewall magazine. “All these pieces do that in a very slow, almost non-invasive way. It’s a very quiet, slow destruction.” The sculptures may slow down the impact of destruction, but they also create ruins of the future, lingering on what remains. UK writer and critic Brian Dillon, in his article for Cabinet magazine called “Fragments from a History of Ruin” noted that “the ruin is not the triumph of nature, but an intermediate moment, a fragile equilibrium between persistence and decay.” Arsham’s sculptures seem to occupy this space of equilibrium: his use of crushed glass reflects both the material’s delicacy and sharpness, while the volcanic ash is a quiet, muted residue of a violent upheaval. The materials contain the remnants of destruction while offering something present and timeless.

For Arsham, his objects are deeply connected to ideas of excavation and archeology: the artist and his assistants actually done lab coats when working in the studio and during installations. For his Reach Ruin exhibition at the Fabric Workshop Museum in Philadelphia in 2012/13, he described himself as adopting the fictional role of an archeologist from the future. The lab coat is but one of the many performative aspects of his practice. Alongside his objects, another key sculptural element is his figures, often cast of resin and fibreglass, but also of broken glass. In the ones made of smashed glass or ceramics, the poses are often contemplative and quiet, whereas his fibreglass figures are almost violently active, singular bodies straining against hugging swaths of fabric that often cause them to merge with the architecture. The artist almost exclusively casts full-body sculptures of himself — he says the process takes about four hours in which the body is completely enclosed, and while he’s attempted to cast other people, they tend to panic after the first hour. Although he did recently make a successful full-body cast of Pharrell Williams, the pop musician with whom Arsham has collaborated in the past, and who has curated Arsham’s work into two recent exhibitions in Paris.

The combination of full-body casts and sculptural objects in a gallery space create an environment, one that reflects a modern-day Pompeii. The artist himself has made reference to the disaster of AD79, one of history’s most famous. When Mount Vesuvius erupted, Pompeii quickly succumbed to layers of volcanic ash, which had the unique effect of preserving the remains, both objects and bodies. Tourists today can witness a time capsule reflecting a single day in Roman history, in part due to the archeologists’ practice of injecting plaster (today, they use resin) into the voids left behind in the ash layer, creating full body sculptures of figures posed in the moment of their deaths from the volcano’s incredible heat. In Arsham’s work, recent natural disasters and those long past come together. Civilizations may evolve and change, but natural disasters are steadfast — a Category 5 hurricane like Andrew was just as powerful in 1992 as it would have been hundreds of years ago, or in years to come. It lends time a certain consistency that equates past, present and future. For Arsham, it’s this awareness that takes his objects out of any one time trajectory, and allows them to exist in a place where time is unhinged from linearity.

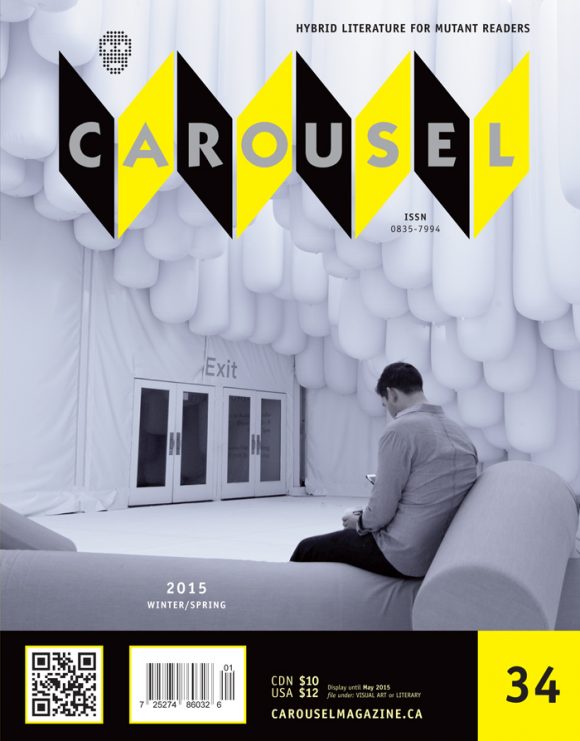

Arsham’s collaboration with Alex Mustonen, Snarkitecture, is a venture that frequently operates in a more commercially-minded arena, while reflecting much of the same visual tendencies of Arsham’s solo art practice. With the idea of destabilizing perceptual experience in pre-existing environments, the pair has developed installations for fashion, music and fragrance labels, among other ventures. At a recent edition of Design Miami, for instance, they altered the pavilion entrance with a collection of inflated tubes hanging from the ceiling, working with the same white vinyl material typically used in such “tent” spaces to unexpected ends. In these environments, the scale tends to be large, the means tend to be relatively simple (inflatables have been used a few times), and the spaces tend to be disorienting (people often find themselves looking up). Snarkitecture also designs functional objects, including white gypsum “pillows” used as nesting spots for iphones, light fixtures surrounded by layers of felt, a cabinet that appears to be broken in half, and a couple of different table designs with undersides that reveal carved “landscapes” and surfaces made for table tennis. The theme of excavation, re-imagined material use and monochrome palette that often figure in Arsham’s independent practice resurface in Snarkitecture’s spaces and designs, but in a more publically-minded way that engages a cross-section of art, design, architecture and commerce. It also speaks to Arsham’s distinctive ability to step between the “insider” art world and a broader community with seeming ease, and without compromising a level of artistic integrity. It’s likely this ability that accounts for Arsham’s widespread reputation.

Daniel Arsham: Relics for the Future

appears in CAROUSEL 34 (2015) — buy it here