From the Archive: Kioskerman Interview (CAROUSEL 34)

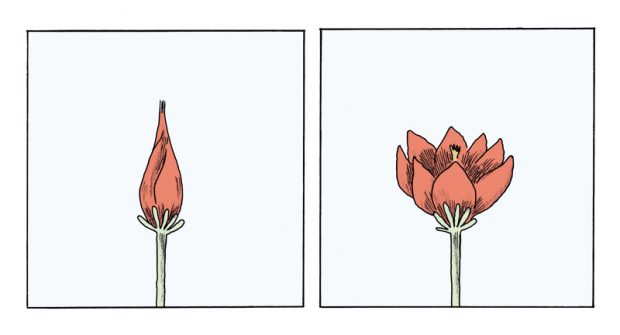

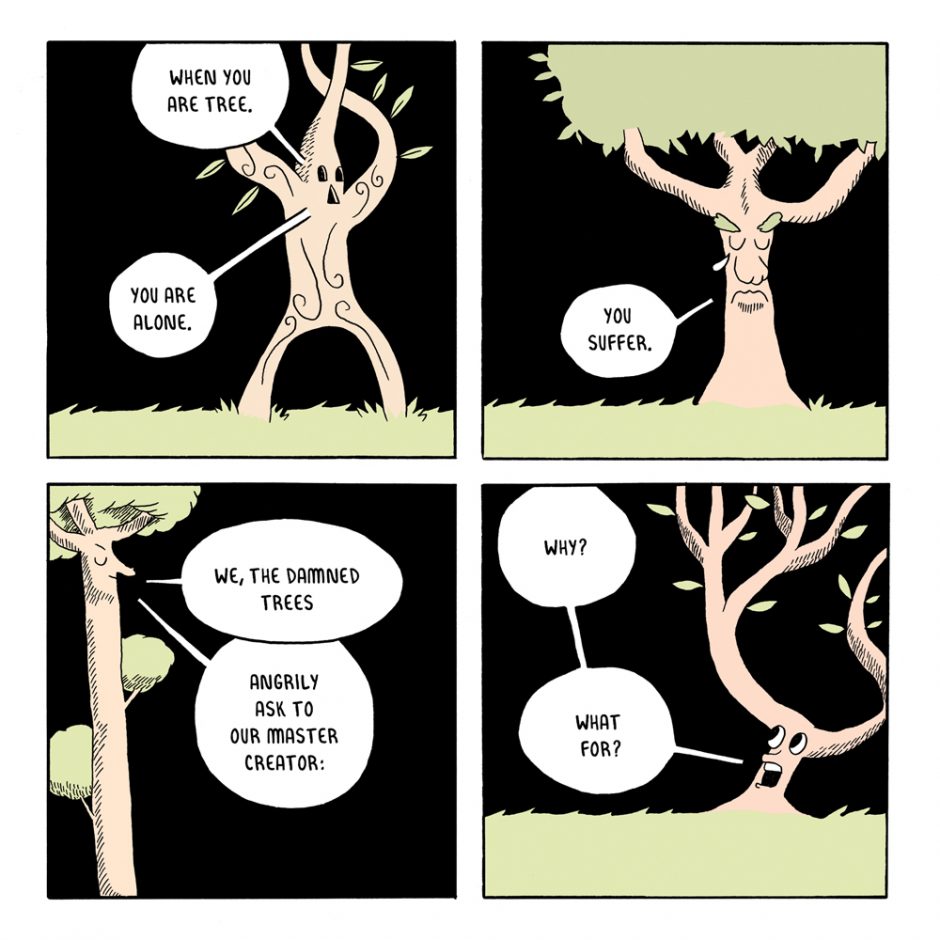

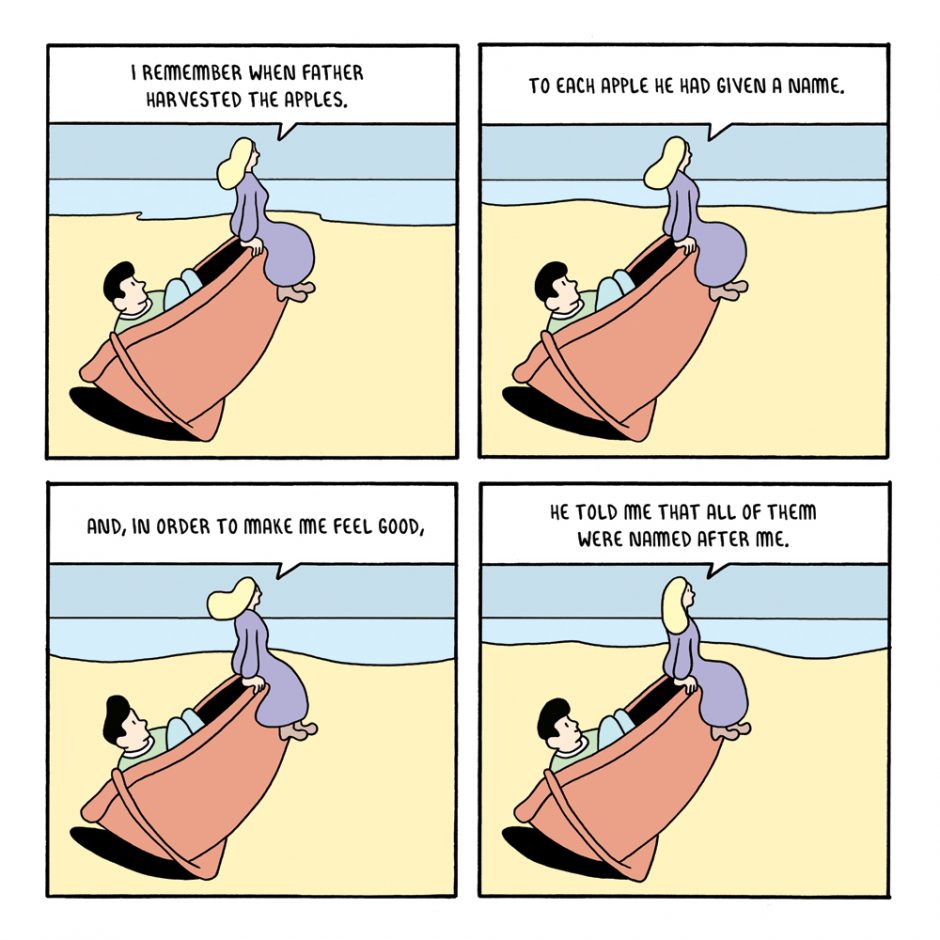

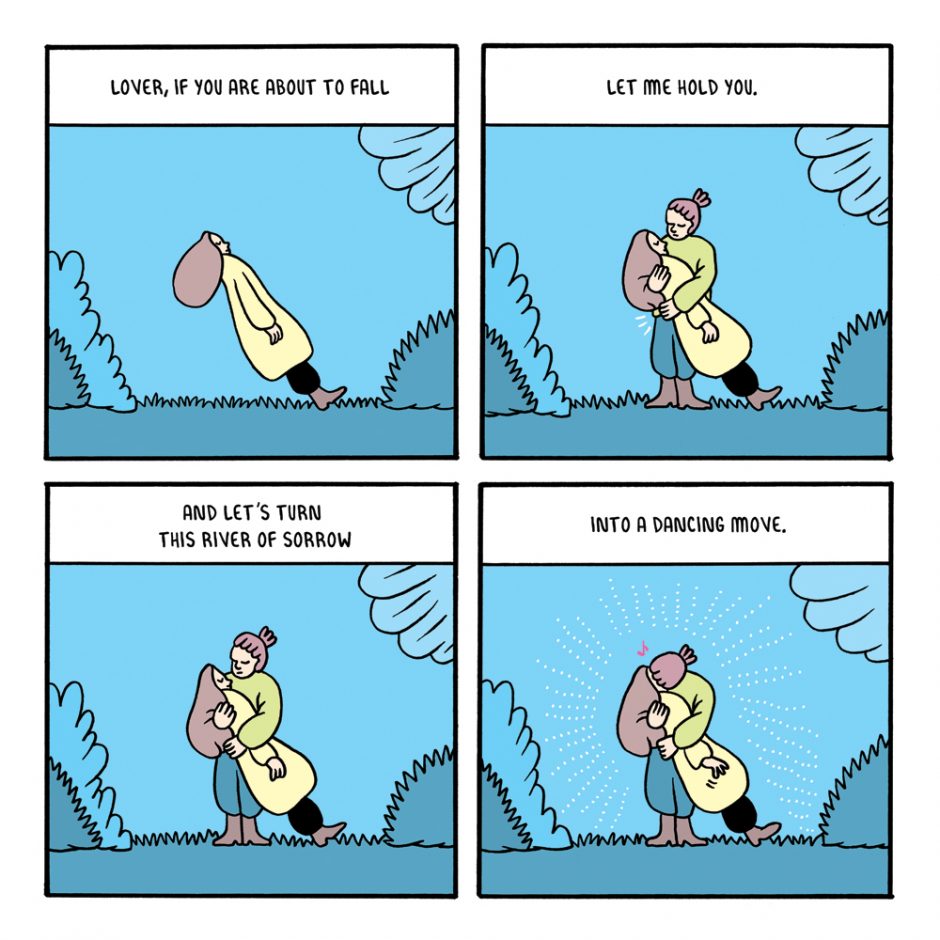

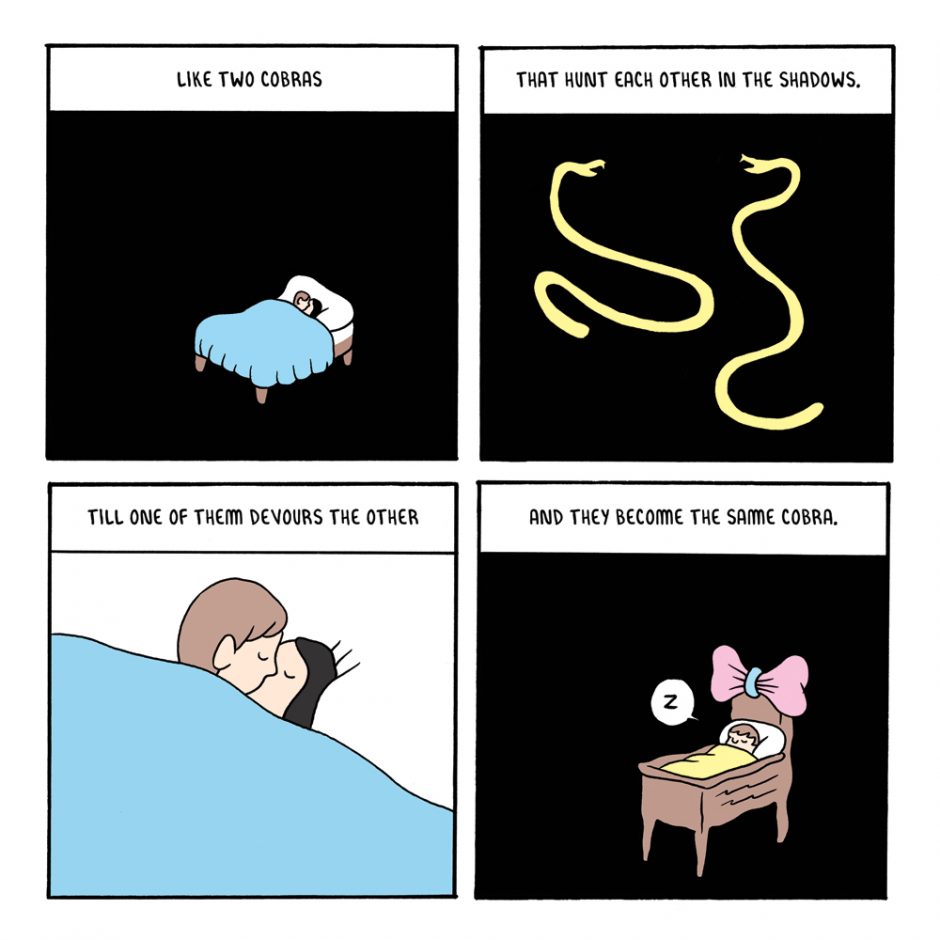

Cartoon minimalist Pablo Holmberg — better known in Argentina under his pen name Kioskerman — makes four-panel comics that elude easy description. His darkly romantic strip series Edén appears in Spanish every week on his website, offering readers an ideal mix of weight & whimsy.

Interview conducted October, 2014

You’ve been publishing strips on the Internet since 2004; why did you decide to start a web-comic?

I was reading Tony Millionaire’s Maakies and Kaz’s Underworld online on a weekly basis by that time, and realized that as a format the short format strip worked very well on the Internet; I still find it hard to read more than one page of a comic online. The experience of reading those strips inspired me to try my own thing; I saw an opportunity there.

Why do you choose to author your online strips solely in Spanish? Is the English market important to you?

I want Edén to be accessible to the world. However, writing is the part of making comics I enjoy most, so it came very natural for me to write in my first language. Though it crossed my mind on several occasions to write the strip in English, I don’t feel confident enough with the language to attempt this on a weekly basis. There is, however, an English translation of Edén (2010) by Drawn & Quarterly that’s easy to find; I participated in that translation.

Comics are a medium where the majority of creators are embracing the ‘novel’ as an architecture; you’ve chosen a different path. What attracted you to dedicating yourself to the strip format?

I like economy, and messages that are simple and direct but that say something deep and powerful at the same time. I like that kind of impact. I love how a strip allows me to represent the spontaneity of an idea. Almost all of Edén’s strips have been improvised in the moment; I don’t rework them too much.

After the first Edén book was published I tried to make a graphic novel — just to have the experience of it. But when I reached page fifty I realized I had made fifty individual strips. I was still drawing Edén subconsciously. It is as if my mind is wired in that way. There was a time when an idea would pop in my head during the day and I was able to write it down in four sentences to fit four panels very easily. It’s all about the feeling, the rhythm and speed of the format for me.

Charles Schulz has been noted as a key influence on your work. Who are some other influences worth noting, or other creators working in the strip format that you admire?

They come and go all the time. But when I started I remember being influenced by George Herriman, Tony Millionaire, Liniers, John Porcellino, Chris Ware, Bill Watterson’s essays, Bob Dylan, William Blake and Tolkien. The last strip I really loved was American Elf; I find it hard to find a strip I like these days.

Reading Edén is a sweetly surreal experience. It feels light of spirit, but manages to explore big concerns: love, death, time are common preoccupations. How do you balance this?

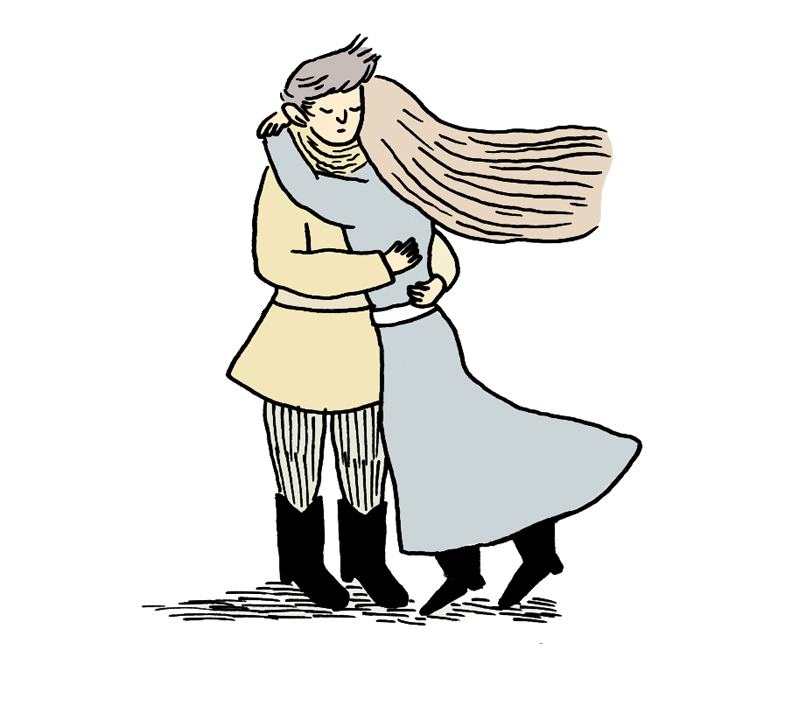

That’s a big part of the power comics have and it’s one of the reasons I like them so much as a medium. You can balance light and shadows in a very effective way by combining text and image in unexpected arrangements. I like that kind of contrast in music too; I was very influenced by Bob Dylan’s way of using traditional folk formats to carry surrealist imagery. In Edén I am showing an idyllic setting but I am talking about the shadowy aspect of life a lot of the times. At first glance it may seem like a children’s book; there’s a kind of irony you don’t perceive until you read the whole thing. People seem surprised by that in almost every review I read.

Does parenthood influence your thinking as you explore this material?

I drew the last strip of the second book of Edén just before my son, who is two years old now, was born. I wouldn’t say parenthood had any influence. But it really surprised me to find that one of the greater themes that moves across the last book, like a sort of leitmotif, has to do with parenthood. Ron Regé Jr. once told me that, “to draw is to attract.” I keep thinking about that a lot, how drawing can attract certain things in your life. Chris Ware got a call from his real dad when he was drawing Jimmy Corrigan. I also read that when Peter Bagge was drawing Hate some of the actions he portrayed in the comic then actually happened in his life, and they weren’t happy endings.

In your first collection, the Forest King takes a forward roll, but even then it’s apparent he’s not really at the centre of things; instead, Nature itself presents as the key protagonist form in the Edén narrative, and the characters are part of the grand scenery. Can you talk about this focus in terms of storytelling?

That was one of my main concerns when I started the strip. I didn’t want to repeat the old formula adhered to by most newspaper strips: place a character or a group of characters with different personalities in various situations and then see how they respond or react. I wanted the situation or the world to be the protagonist. I was not aiming for conflict and characterization either, I was looking to explore my feelings and desires, and I realized that the world itself was the best vehicle for that. If you look at the strips I create, there is very little body language or facial gesturing involved, the characters seem rather like sphinxes. I like that mystery: the eye that doesn’t blink, like a portal between the visible and the invisible. You can’t really know too much about the characters and that’s what I find interesting about them.

Your strips present like snapshots of a fully-realized world; yet, you’ve noted that your personal exploration of Edén lacks background. One gets the sense that you enjoy the wandering.

That’s curious — I once wrote a short introduction for the first Edén book, where I said that Edén was all about wandering and getting lost. I then decided not to publish that text, but it has a truth to it that still holds. I like going to places I don’t know and getting lost. I want to be surprised by the unexpected. But at the same time, I can see the Edén world when I close my eyes very clearly. It’s like drawing from a realpre-existing world, though I find it very hard to put that feeling into words. I don’t think about it; it has

a presence of it’s own. I try to be faithful and represent it in comics as I feel it.

Can you give us an idea of how you create a new strip?

There are different ways in which I create a strip. Sometimes I begin with a text and then try to add something that’s more than merely an illustration of the writing. Or, I start with a drawing of a specific setting and situation. I used to look at old issues of National Geographic that I loved as a kid and try to use places in the real world that are alien to me as a sort of catalyst. In the best case, I can pull off text and image at the same time. I try to improvise the strip in the moment and pencil a first version that will look very similar to the final strip, and then save some days to ink it, colour it and adjust the lettering. If I have to struggle from the beginning — if it doesn’t come at once — I usually throw it away.

As you approach the making of a strip, how do you navigate the interplay of words and images? I get the feeling that words drive

the creation of these works.

Yes, writing is the most important part for me. I didn’t approach comics because I loved drawing; I didn’t really draw much until I started making strips. I just draw them because I feel that nobody else can interpret my imagination as well as I can. I prefer to do it clumsily than have a great visual artist to do it. I am not interesting in drawing per se. I like the way the drawings are used to design the panel and its elements as symbols that are meant to be read and looked at at the same time.

For the physical books, the presentation of your work is altered — your strip format is reformed into a grid. Why do this? Do you think it changes the read of each strip?

At first I wanted the books to have a rectangular shape, like the Maakies collections from Fantagraphics. The square format was a suggestion from Chris Oliveros, my editor at D&Q. I do think it alters the pacing a little, but I am very happy with the decision.

Why did you shed your pen name when you released the Drawn & Quarterly Edén book?

Chris Oliveros suggested that I not to use a pen name in North America. He understood pen names are very common in Argentine and European comics, but he thought it would be a hindrance for my introduction as an author to North America.

Will the North American market see another English-version Edén anthology any time soon?

Who knows. I would love to, but I haven’t found a willing publisher yet.

Kioskerman Interview

appeared in CAROUSEL 34 (2015) — buy it here