From the Archive: Leah Jane Esau (CAROUSEL 35)

LEAH JANE ESAU

Letters to Your Brother

Hour One: we aren’t sure what happens in the first hour he goes missing, because we aren’t there.

Does it happen because we aren’t there?

•

Hour One for you: a phone call.

You don’t answer because your shirt is on the floor of your boyfriend’s apartment. You let it ring three times and go to voicemail.

A few seconds later, it rings again.

Your boyfriend says, “Maybe you should see who it is,” and you do because the mood is ruined anyway.

It’s your mom.

“Have you seen your brother?” she asks.

“No.”

“He’s not home yet.”

“I’m sure he’s fine, Mom. He’s probably just out,” because Jay is seventeen and can take care of himself.

“He said he’d make dinner. He left at four thirty to get groceries.”

This surprises you because it’s just after midnight, and it’s unlike your brother not to call if plans change.

“I’m sure he’s okay. There must be some explanation.”

Possible explanations:

1: there was a miscommunication, and your brother never intended to cook dinner; he’s making out with his girlfriend, and, unlike you, he had some sense to turn off his phone.

2: your brother flipped the van in a ditch and is working up the courage to call home.

3: your brother is at the movies.

4: your brother is at a party.

5: your parents haven’t checked their answering machine.

These are only a few possible explanations.

Hour Two: a police car in the driveway.

Your mom explains that she’s called all of Jay’s friends, and all of the hospitals in case there was an accident.

Just then, your dad returns with Jay’s girlfriend, Jenny. They’ve been out to all the familiar places: the cinema, the ravine, the lookout.

“Have there been problems at home?” the officer asks. “Did you get in a fight?”

“No,” your dad says.

“Even a small disagreement. Was he upset about anything?”

“Not that I know of. Jenny?”

“No,” she says.

“Does he have history of mental illness?”

“No.”

“Was he in trouble at school?”

“No. Not that we know of.”

You don’t see how your brother’s grades are relevant, but still, they ask for his report card.

The police look at the report card.

The police say your brother is seventeen and probably ran away.

“We see this sort of thing all the time. He’ll be back in forty-eight hours or less.”

“But everything’s here,” your mom says, “his clothes, his camera. He doesn’t go anywhere without his camera.”

She’s right. Your brother is an aspiring photographer, the Nikon is his baby.

The police spew statistics: teen reported missing, teen returns home in forty-eight hours or less. They repeat forty-eight hours, and perhaps this is why you begin counting.

The police leave. You wonder if they would take this more seriously if your brother were a girl, or an Honours student, or a child. And he is legally a child.

You say, “I’m sure he’s fine,” but your parents are worried, and so you get back into your car and scour the city.

Hour Three. Hour Four. Hour Five. Hour Six. You search, and search for your missing brother. In another car, your dad does the same. You start to drive places you’ve never been before. This is crazy, you think. He’s fine.

Hour Eight: morning. Your brother has been “missing” eight hours.

You’re not sure what the word “missing” means. When does someone actually go missing? Is it the moment they become “lost” or the moment people realize they’re gone?

“He’s recovering from alcohol poisoning,” you say even though that’s never happened before, and Jay doesn’t drink much. “One of his stupid friends’ll take him to get his stomach pumped.”

Right? Right.

Perhaps because he was a young man once and understands these things, your father has another theory.

Once, when he was seventeen, he and a friend skipped school and drove to a small town, about an hour down the highway. They arrived before realizing they’d run out of gas and, of course, had no money.

“And that’s how young men are, spontaneous and disorganized.”

Hour Nine: your father drives to the nearest town, hoping to spot the van on the side of the highway. Maybe your brother decided to be spontaneous. Maybe he ran out of gas. Maybe he has a flat tire. Maybe you’ll find him safe and sound, sleeping in the back of the van.

In the meantime, you call his friends. They call their friends. The school is notified. No one has seen him. You call the hospitals again. You wait for news of an accident. You don’t want this news, but you want this news.

You call the police station.

The receptionist says, “Thanks for notifying us. We’re working on it.”

Except, you realize, the police didn’t even ask for a picture.

Hour Ten: you don’t know what to do, so you begin printing flyers. Is it too soon to print these flyers? No. Every second counts. Every second you could be doing something that will help.

A strange feeling comes over you as you try to pick the best photo: this one, where his face is close-up? Or this one, with his whole body?

Just the face, you decide.

The photo comes out of the printer: grainy, with ink-lines. You take the photo to a print shop.

“How many copies?” the woman asks.

This is an impossible question.

Hour Eleven: your boss calls because you’re late for work. You’ve completely forgotten about work.

You explain the situation, and she gives you a leave of absence: “as long as you need,” she says.

For some reason, this makes you angry.

“We’ll find him soon,” you snap.

You don’t realize that, at this point, you haven’t slept in twenty-six hours.

Jay’s friends skip school. Their parents organize a search party. They try to convince the police that Jay wouldn’t run off. Jay’s boss at McDonald’s gives a flyer to every customer. He hands a flyer to each driver at the drive-thru, he puts a flyer on every tray. Your brother’s face sits under a carton of fries. People dab ketchup off his chin and say, “How terrible, so young.”

Hour Twelve: a reporter says, “Friends of the missing teen have assembled a search group. It’s the fastest search anyone has organized for a missing teen.”

Really?

There is some comfort in this.

We’re totally nuts. He’ll be home any minute. We’ll laugh that we called the police, and organized all these people. We’ll be embarrassed.

Hour Thirteen: the house is full. You know these people but their faces are blurred, their voices faraway. Someone says, “You should get some sleep,” and you realize you haven’t slept in twenty-nine hours.

You calculate this in your head. Yes, you woke up just after eight, you went to work, to the gym, to dinner, to your boyfriend’s apartment, and your mom called around midnight: sixteen hours.

And your brother has been “missing” thirteen hours since then.

But you’re not tired at all. You have to find your brother.

“When was the last time you ate something?”

You don’t know the answer so you’re made to eat a sandwich. You chew slowly. The bread gets stuck to the roof of your mouth.

He’ll be home any second, is repeating in your head.

You refuse to sleep. You distribute more flyers. You speak to waiters, and managers, and clerks. Hour Fourteen. Fifteen. Sixteen.

Hour Seventeen: you faint from exhaustion in a 50s-style diner where you and your brother once had a milkshake. You wake up on the floor with people hovering.

You decide it’s a bad idea to drive. You leave your car parked somewhere. You ask the taxi driver to pass by the arcade before going home.

You think, forty-eight hours is a very long time.

Hour Nineteen: your aunt gives you a sleeping pill and you sleep because you have to.

This could be the moment something bad is happening. This could be the moment he’s going unconscious, or he’s waking up in a ditch, or he’s getting beat up. Oh, God.

The sooner you do something, the sooner this moment can be good for him.

You have to do something, you have to do something, you have to do something.

You sleep.

Hour Thirty: you emerge to see the state of the house. The living room full of people, the kitchen full of food, the front yard full of reporters and posters and a search team ready to start — everywhere full, but empty of the person you want most.

Your mother is in the backyard. You cannot describe her. You’ve never seen anyone in so much pain.

“Did you sleep, Mom?”

She shakes her head, and then you’re angry.

He’s going to kill her!

That selfish bastard.

Hour Thirty-Three: it’s now 10 a.m. The police admit it’s unusual, but say, “let’s give it another fifteen hours.”

You want to strangle the officer. Instead, you try reason. You calculate in your head, you say, “Is it forty-eight hours from when he went missing, or from when we notified you? He was last seen at four thirty, but we didn’t notify you until midnight.”

The officer says those are the rules, and there’s nothing he can do.

“But, sir,” you say, “fifteen hours from now will be one in the morning. I’m concerned that you won’t have the manpower to search at that hour.”

He considers this.

“Please. I know he’s a teenager, but he’s still underage. Isn’t there anything you can do?”

Hour Thirty-Four: the police break protocol and declare your brother officially missing.

“Officially missing.” How strange this concept is.

Things finally happen: a citywide alert is issued. The Missing Person’s Unit arrives with canines. They ask for a photo of Jay. They interview his friends.

Hour Thirty-Five: you join one of search groups in the woods and along the river. By hour Forty-Four, the police call off their search for the night. You’re exhausted but the adrenaline keeps you awake. You search the city: the same places you’ve already looked. You look, and look, and look again.

All night the same four words:

Where is my brother?

Where is my brother?

Hour Fifty-Seven: you wake up, folded over the kitchen table. You don’t know how you made it through the night, but you did. The police have no leads. They stomp through your kitchen.

A volunteer makes coffee in your coffeepot.

“We’ve issued a National Alert.”

You think about how far your brother could drive in fifty-seven hours.

Maybe his car was hijacked and he’s driving to Mexico at gunpoint.

No, that only happens in movies.

Hour Fifty-Nine: a press conference. The police instruct your parents to speak to Jay, to ask him to come home. This insinuates that he ran away, but your parents are grateful for media attention. Your mother tries to form sentences to the camera.

“Please Jay, please, come home.”

And your father: “If there’s anyone out there who knows something, or maybe you’ve done something wrong, please, you don’t have to turn yourself in, we just want our son back. Any information is helpful.”

Hour Sixty-One: Jenny returns from a search. Instead of going to her house, she comes to yours. She spends some time in Jay’s room, crying. She emerges, exhausted, black under her eyes. Was she always this thin?

You make some tea, and it’s just the two of you in the kitchen.

“I’m going home,” she says.

“Yes. That’s a good idea, in case Jay drops by.”

She squeezes Kleenex into little balls. Her fingers are small, with little pink nails.

They’re just kids.

They’re just fucking kids.

The police make a final push. They don’t tell you it’s a final push, but that’s what it feels like.

“The first seventy-two hours are crucial to finding a missing person,” they tell the volunteers.

You really want to strangle the police officers.

•

Day Four: you are in a grocery store, a little girl hits her brother on the nose, and he starts to wail.

“Don’t do that. Be nice to your brother,” their mom says.

What was the last thing I said to him? Was it about the scrambled eggs? The day before he went missing, he called.

“How do you make scrambled eggs?”

“What do you mean?”

“How do you make scrambled eggs? Mom’s not home.”

You rolled your eyes. “Crack some eggs in a bowl. Add milk — ”

“Wait. How much milk?”

“A little.”

“How much is a little?”

“I don’t know. A quarter of a cup.”

“Hang on … milk. Okay. Now what?”

“Beat the eggs.”

“How do I do that?”

“With a fork.”

“I just … poke the eggs?”

“Pour into the frying pan. Keep stirring until it’s done.”

“Wow, that’s easy!”

And then what? Did you call him an idiot? Was that the last thing you did to your brother: make him feel stupid? You can’t remember what you said.

Was it: “have a good day”?

Was it: “come over sometime”?

Was it: “I love you”?

Why? Why wasn’t it that?

The end of Day Five: night.

You go into his bedroom.

The police have already been here, looking for clues. His camera sits on the desk.

The last photos he took: a close-up of a bee, a boy playing baseball, a cat hunting in the backyard; and then: the cat has caught a bird, live action. This is an amazing

photograph. The cat on her hind legs, gripping blurry wings, mouth open, baby fangs.

You start to cry. Perhaps you cry because nature is brutal. You knew this before, but now you know it.

You take sleeping pills.

Your brother arrives in a blur, and sits on the edge of the bed — you feel the weight on the mattress.

He’s here! He’s here! He’s —

You wake up to your parents at the door.

“Are you okay? You were screaming.”

“Oh.”

You wipe away tears.

“I was?”

For a second, you consider telling them.

“It’s nothing. I had a bad dream.”

Day Six: they look for your brother.

Day Seven: they look for your brother.

Day Eight: the police call off their search and everyone goes back. Everyone goes back to their jobs and their friends and their lives. Not you: you are stalled.

You go on somehow. You go to therapy, to support groups. You live in a state of things unsettled, unsolved, unanswered. You can’t grieve because you don’t believe he’s dead.

Three years later you run into Jenny, and a new boyfriend. It all goes fine, but then in the car afterwards, you can’t stop crying. Bursts like this happen: you’re fine, you’re fine, you’re fine — you’re overwhelmed.

Where is my brother?

Where is my brother?

•

This is how you think of him.

He drove the van down the coast. He was sick of school, and homework, and his fast-food job.

Now he lives near the beach, somewhere south. He shares an apartment with a friend. No — it’s a house, a beautiful beach house with an ocean view, owned by an old lady who likes to knit. She keeps the rent low, and in return, he cares for her: he makes dinner, and puts gas in her car, and plays scrabble.

He’s become a photographer, and he pays the rent by selling photographs. He uses pseudonyms online, which is why you haven’t found him yet, but he’s out there. He likes to do things with his hands. On the weekend he takes pottery classes, and grows exotic plants: little hobbies.

Years pass. You write him letters, and birthday cards, and postcards from places you travel. In the letters you say things like, “Today it rained, but we went to The Colosseum anyway,” or “We celebrated Dad’s birthday at the cottage this year,” or “Mom’s chemotherapy has been a success and the doctors are optimistic.”

You keep these letters in a box for him, because one day you will mail them. Because one day you will find him.

You think of him often, and then not, and then often again.

And once a week, in the beach house, you imagine that he makes breakfast: toast and bacon and scrambled eggs. His scrambled eggs are perfect. The best the old woman has ever tasted.

Letters to Your Brother

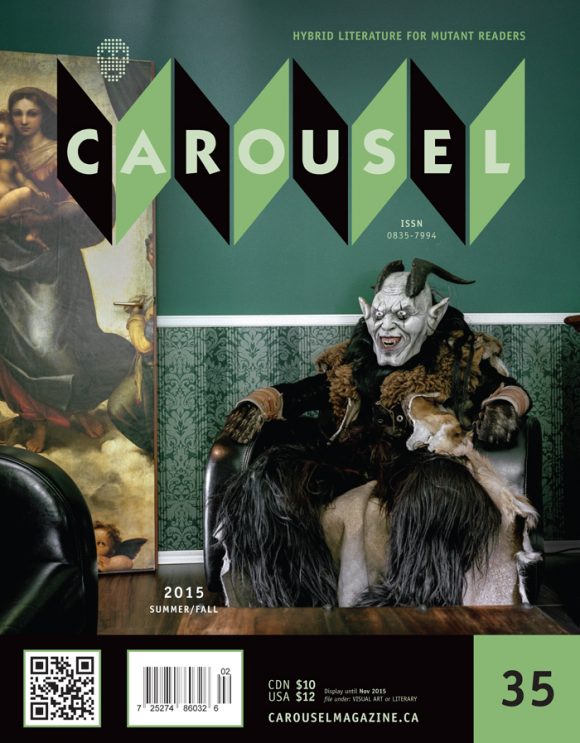

appeared in CAROUSEL 35 (2015) — buy it here