USEREVIEW 025: Swivel Sights

Karl Jirgens proceeds by paradox — with an outward-looking and self-reflexive gaze, with enthusiastically energetic aplomb — in this not-quite traditional review that echoes the stylistic elements of its subject: Ken Babstock’s poetry collection, Swivelmount (Coach House Books, 2020).

ISBN 978-1-55245-4138 | 128 pp | $21.95 CAD

#CAROUSELreviews

#USEREVIEWEDNESDAY

In preparing this review for CAROUSEL, I thought it’d be interesting if book reviews reacted rather than described or interpreted. After all, writing ought to open dialogues. Dear Ken, thanks for the poems in your new book, Swivelmount. Some swivel-mounts turn from side to side, others tilt up and down. Poems in this collection swivel through multiple visions, thoughts, memories. This collection opens with quotes from Agnes Martin and Samuel Beckett. Martin says:

Nature is the wheel

When you get off the wheel you’re looking out

You stand with your back to the turmoil …

I wonder, is “turmoil” the wheel itself, or is it found on the wheel? In 1997, Martin created a 6-canvas suite titled, “With My Back to the World” exemplifying art situated outside of worldly turmoil. But, if there’s a wheel that Babstock climbs off of, then he’s facing the wheel, facing nature (including human turmoil). Echoes ensue. The grid-lines of Martin’s paintings indicate her hermetic lifestyle, echoing Rothko’s paintings. Lines in Babstock’s poem “Homeoteleuton” echo Paul Klee’s visual-lines, echoing John Berger who, in his TV-series Ways of Seeing (1972), said, “If I’m a storyteller it’s because I listen. For me, a storyteller is like a passeur who gets contraband across a frontier.” Babstock as passeur discusses some things but he’s really gesturing to other things.

Canadian-born Agnes Martin, an Abstract-Expressionist painter, spent most of her life in New Mexico. Martin praised Latvian-born Abstract-Expressionist painter Mark Rothko for having “reached zero” because his minimalist paintings achieved transcendent actuality. Martin’s perspective links neatly with the opening quotation from Samuel Beckett where he says, “When it’s there it’s there and when it’s not it’s not and basta.” Babstock’s poems inter-weave complexities of presence/absence, memory/actuality, turmoil/calm, and being/nothingness. Martin and Beckett reduced their chosen media to fundamental forms, zero-level minimalisms, and resonating actualities beyond those that lie before your eyes.

Evaluations of this collection abound, often echoing this book’s jacket-notes which feature praise from Rae Armantrout (poet), Dan Bejar (musician) and Miriam Toews (novelist). I’ll add that Babstock grips readers and actualities through meticulously chosen words often evoking what isn’t there. Babstock’s legerdemain magically causes disappearances from your open hand, before your very eyes.

This collection opens with “Self-Portrait, 1864 Self-Portrait, 1896 Self-Portrait” and the lines, “I started dragging Cézanne / on Twitter — the bot posting / canvasses, no discernible order.” That poem’s narrator states that Cézanne’s birthday “is my birthday”. Co-incidence: Cézanne; b. Jan. 19, 1839. Babstock b. Jan. 19, 1970. Parallels arise in this self-reflexive, meta-linguistic, self-portrait offering neo-Hesiodic directions on vision and re-envisioning, while cross-referencing Cézanne’s self-portraits.

Cézanne’s early self-portraits are called “Late-Romantic.” Later ones, “Post-Impressionistic.” In Cézanne’s 1864 self-portrait, his head tilts downward, eyes upward, glaring at an imagined audience with what? Psychosis? Resentment? Menace? Like a Stanley Kubrick character. In Cézanne’s 1896 self-portrait, he’s mellow, affable, plump, perhaps curious or befuddled, older, with greying hair. Intriguing changes. What’s Babstock saying about himself?

Babstock’s self-portrait poem incorporates tangential narrative ruptures, listing disjointed personality traits. It concludes 6 pages later noting the “fan-and-bubble-drama,” of “rock,” stating that “the mountain never / returns whole from having / been worshipped to pieces.” This ruptured self-portrait lists traits including “fiscally infantile,” “devoid of long-term episodic memory” and, “… in pubs, hyperpareidolic / ornery, saturnine, vengeful, / glum, and given to huffing.” The symptoms of pareidolia arise when individuals find meaning in perhaps meaningless things (coincidental numbers maybe, or “seeing” Jesus’ face on a piece of burnt toast). Personality traits in this ekphrastic self-portrait cross-reference to “Paul” (Cézanne) and Susan Sontag, until the narrator confesses, “I’ve lost / me again.” I conclude that all portraits or self-portraits are assemblies of fragmented bits, including and emphasizing some features, while excluding others.

True to pareidoliac form, the collection moves to the poem “Edge,” linking observations on cutting edges of stone-saws, pneumatic drills, diamonds, corundum and a cut-shot while shooting pool. Babstock’s spatial-temporal leaps spot analogues including corundum’s hexagonally-packed oxygen ions, stone-saws, drilling, fracking and grit on pool-cue tips: “The six, / a kiss, in the side / pocket” (empty space prior to the word “pocket” marks the near-silence before the ball drops into the pocket). Sixes. Hexagons.

The poem, “Tasked with Designing the Vienna House” appeared previously in GRANTA. Many poems in this collection were previously published in respected Canadian and international periodicals. I searched for backgrounds on the “Vienna House” and found that Labvert was tasked with renovating a gorgeous 19th-century Viennese Gründerzeit building [Stephan Vary, architect] for a wealthy client who travelled between Paris and Vienna. This poem’s narrator confesses that the Vienna House and surrounding region are “constantly appearing as paper.” A dystopic visual tour blurs actuality with representation, combining a “Sky of bright rust and / soapy aquamarine” with a nearby “expressway,” “graffiti,” “a quayside bar in Rotterdam,” with “de Kooning’s mom’s hotel,” and “hard drugs.” Babstock’s perspicacious allusions recorded on paper, demand intense reader-engagement. I keep checking vocabulary, allusions. For example, near the end, this poem shifts to an acoustic dimension with Tranströmer playing Ravel’s “Piano Concerto for the Left Hand,” composed for “Wittgenstein’s brother / who’d lost his right hand in the war.” Tomas Tranströmer (1931–2015) was an esteemed Swedish poet, psychologist and translator. Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951) was an Austrian-British philosopher working with logic and philosophies of mathematics, mind and language. Ludwig’s brother, Paul Wittgenstein (1887–1961), was an Austrian-American concert pianist known for commissioning piano concerti for the left hand, following the amputation of his right arm in WW1. Maurice Ravel (1875–1937) composed “Piano Concerto for the Left Hand (in D major).” The Concerto premiered in 1932, with Paul Wittgenstein as soloist, performing with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra. Here’s a version featuring Yuja Wang playing that concerto; and here’s Tranströmer reading poetry and left-handedly playing piano (because he had a stroke).

Babstock often visits sub-genres such as music compositions for the left-hand. The poem closes with a (Ludwig) Wittgensteinian play on language, “A vessel bursts in my right eye. / A vessel leaves port bound for my / right eye.” This polysemous language-play raises more questions than answers. Did an ocean-going vessel burst into the narrator’s line-of-vision, or did the narrator experience a medical situation involving a burst ocular vessel? It doesn’t matter. This poem-as-tour blurs interior and exterior spaces, blending thoughts with surroundings. Babstock’s poems generate what I call (elsewhere) a neo-Baroque sensibility. That sensibility is shaded by fugue-like layers of sound and vision, with a jazz beat, (“Milk and Hair”), sometimes truncated (“Another American Massacre” and “Precious Ally”), sometimes a prose-poem (“Keeper” and “Puma Dalglish Silver”) and always a dialogue (with the reader) or an internal-dialogue within the poem (as in, “Hexi Telly” featuring “the desert / of civility,”) and always presenting some “FaceTime” on the printed page, generating presence from absence, as in “;comma;” (written “after Graham Foust”): “The first smart phone / was a Rubik’s cube, / the first Rubik’s cube / a snuff box, the first / snuff box likely bone / beading.”

The poem “Aubade from Security” skews tradition. Typically, an “aubade” is a morning song by someone leaving their lover. In this poem, “dabbing my cheek like an otter,” the narrator, at “St. Pancras” (railway station, London), opposite the “Crick” medical institute, communicates with a lover who sends a “fence of Xs” (via iPhone?), leaving the narrator in “sock feet” to face a medical exam, in a sick world.

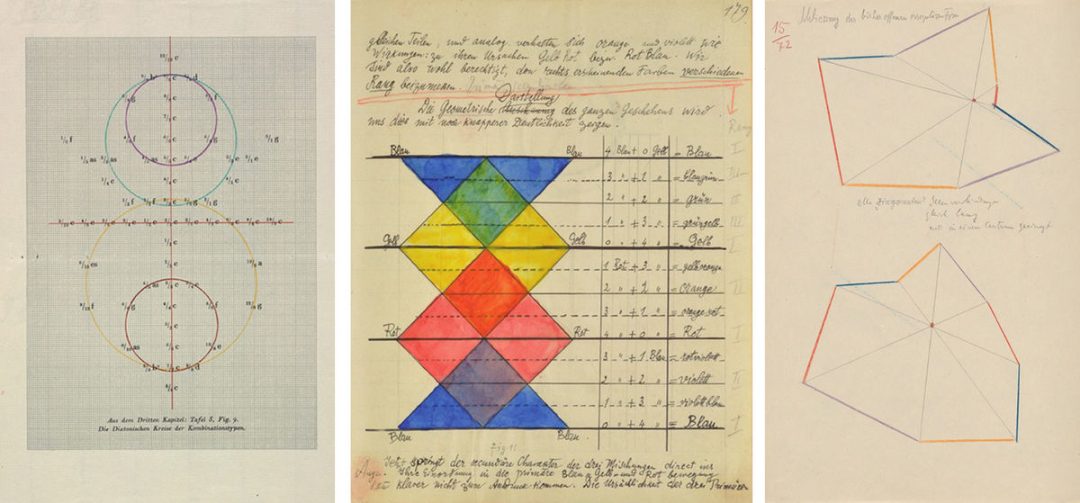

That poem is followed by “Homeoteleuton,” (i.e. the repetition of words at line-endings; a near-rhyme) which hop-scotches through Berger, NASA and “Klee’s online Bauhaus / notes on colour and line” paralleled by an attempt at a mimetic graphite drawing of an iPhone, which ends up thrown, “headfirst down a flight / of stairs” thereby re-arranging the drawing’s angles in a movement of mind, leaving graphite still inside the pencil “the soft lead still in wood.” Klee once said: “Zero equals Two!” The discarded drawing (“zero”) results in more than “two” statements. Here’s a Klee image from perhaps the same on-line site mentioned in this poem (“Lesson #1: “Take a line for a walk”):

See also: Paul Klee’s Pedagogical Sketchbook (Faber & Faber, 1953-1981).

I’ll stop my reaction here, having reached this review’s word-limit, though I’ve only begun to trace thought-lines threaded through this tapestry of coloured intimacies. Babstock challenges readers to get off their duffs, expand horizons, revise thought-patterns. Poems such as “Clotho, Lachesis, Atropos” gesture to Greek fates, spinning, dispensing and cutting the threads of human destiny. Babstock’s poetic parallaxes demand deep reading, lament lost lives, revel in the fabric of experience, light on historical figures (Francis Crick, Franz Kafka, John Berryman, Walter Benjamin, Christopher Robin), fly from linear-logic to lateral-associative meditations on perception/recollection, sometimes arriving at, “Beached Squid and Ideas of Order” (recalling Wallace Stevens) to contemplate parthenogenesis while asking, “but are you sure you’re all right / being in love / with me because I’m not all that functional.” So, prime your abducens nerves! Enter Babstock’s pareidoliac word-realm. And, remember, “Time is slower at / the top of a six-foot ladder.”