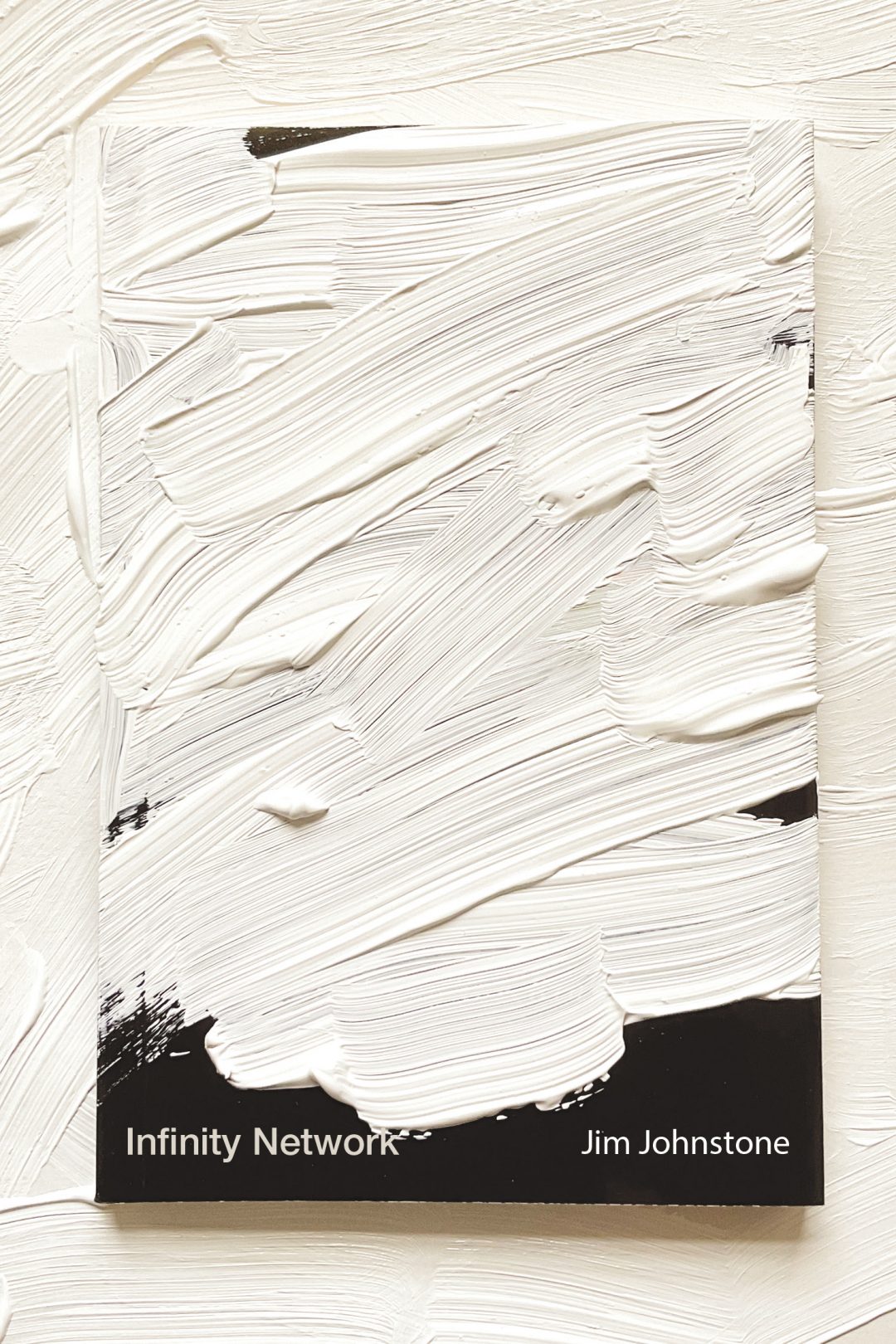

USEREVIEW 097 (Capsule): Infinity Network

Jim Johnstone

Infinity Network (Véhicule Press, 2022)

ISBN 978-1-55065-591-1 | 78 pp | $19.95 CAD | BUY Here

#CAROUSELreviews

#USEREVIEWEDNESDAY

Eternity is rendered a slender chronicle in Jim Johnstone’s latest poetry collection, Infinity Network. Where his previous book, The Chemical Life (2017), examined the self as an entity mediated by medication, recreational drugs and various other forms of biological intervention, Johnstone’s current work considers how our identities are incarnated and refracted through the prism of digital media. As if offering us an antidote to the plethora of copious (mis)information that proliferates uncontrollably online, Johnstone approaches his subject with language that is fine-tipped, gleaming and precise as a silver dart sinking into the vast, dark fibres of the penetrable (but often inscrutable) internet.

This brevity is accomplished, in part, by Johnstone’s skillful use of implication — his studied approach to form and diction achieves as much as the explicit content of the text. In poems like ‘The Outrage Industry,’ for instance, Johnstone repurposes the traditionally romantic sonnet and turns it into terse, satirical verse in which even the normally sympathetic, lyric ‘I’ speaker is an unrepentant, unsuspecting patsy for our collective cultural failings, spouting familiar but off-putting sentiments like: “the more we talk, / the more I’m convinced I’m right.”

I read somewhere once — in an essay I can neither find nor forget — that unhappy poets like Sylvia Plath write predominantly in the lonely first person singular (‘I’), while happy poets like Billy Collins prefer the solidarity of first person plural (‘we’). Whether this is true in general, I can’t say, but for Johnstone, ‘we’ is decidedly not a signifier of contentment; rather, it’s a pronoun of conspiracy (“we can work around the truth”), critique (“We can’t help but see things as we are”) and dread (“We’re safe everywhere until we’re not”). And yet, by cynically and counterculturally refusing to see shared experience as an inherent good, Johnstone offers us brief respite from the toxic positivity and false friendliness that characterizes so much of our social media lives. He might even, paradoxically, be giving us a glimpse of existential communitas.

Recommended excerpt:

For a moment of levity, try ‘Two Sleep Through’ (p. 58) which, though it ends as ominously as all the other poems in the book, is rhythmically quite chipper, skipping along a series of internal (and slant) rhymes, buoyed by bouncy assonance and consonance.