USEREVIEW 132: Impossible Longings

In this special edition of USEREVIEW, section editor Jade Wallace reviews three seemingly very different books: a novel, a graphic novel and a collection of poetry. What unites all three is an impossible longing to return: to a time, to a place, to a self that is forever lost.

#CAROUSELreviews

#USEREVIEWEDNESDAY

Brooke Lockyer

Burr (Nightwood Editions, 2023)

ISBN: 978-0-88971-442-7 | 288 pp | $22.95 CAD | BUY Here

It is easy to draw comparisons between Brooke Lockyer’s Burr and Erica McKeen’s Tear. Both are debut novels set in or near London, Ontario; both draw on tropes of Southern Ontario Gothic fiction; both centre young female protagonists who are isolated and lonely; both have monosyllabic names with multiple implications. But where Tear starts out quietly and ramps up into violent monstrosity, Burr remains an understated ghost story throughout.

Burr’s primary focus is teenager Jane, whose quintessentially ordinary name befits her entirely ordinary life, coming of age in the 1990s in the small, fictional town of Burr, Ontario. Lockyer seems to delight in peppering the text with 90s nostalgia. Jane’s mother fondly recalls how Jane’s father refused to wear the new Roots sweatpants she bought him for their runs, preferring his old and holey “Zellers sweatpants.” Jane swoons for Tori Amos and teases her best friend about dating a boy who wears puka-shell necklaces. This comfortable, recognizable mundanity is interrupted by the unexpected and premature death of Jane’s beloved father. Suddenly, grief clings to Jane like a burr, haunts her like a spectre that may or may not be real. She isolates herself from her mother — who is having just as difficult a time maintaining any real connection with the people around her — and from her best friend, whom she may or may not have romantic feelings for.

Instead, Jane seeks solace in the company of Ernest, a man who has been stigmatized by the community for decades, ever since the traumatic death of his sister when they were children. Ernest was subsequently in and out of psychiatric facilities, and often at odds with his parents until they both died and he inherited their crumbling old house where he lives alone. Lockyer does an adept job at maintaining narrative tension around Jane and Ernest’s relationship, deftly navigating the inevitable problems therein — whether they be the judgments of the townspeople or Jane’s misunderstandings of Ernest’s intentions — while avoiding any easy generalizations about grown men who befriend young girls.

While Jane is arguably the protagonist of the novel, being the only character whom we’re given first person point-of-view access to, Burr also gives readers third person over-the-shoulder insight into the lives of Jane’s mother, Ernest and even Burr itself, with some chapters zooming back to take a town-wide view of the action. Linguistically, the novel shies away from the poetic and melodramatic qualities often associated with Gothic fiction, preferring instead a more colloquial register and pared-down descriptions. The shifts in narrative perspective, coupled with the casual, conversational prose, give Burr a simultaneous sense of intimacy and social connectivity, and the move to full-fledged supernaturalism toward the end of the novel surprisingly but aptly serves both of these impulses.

Rawand Issa

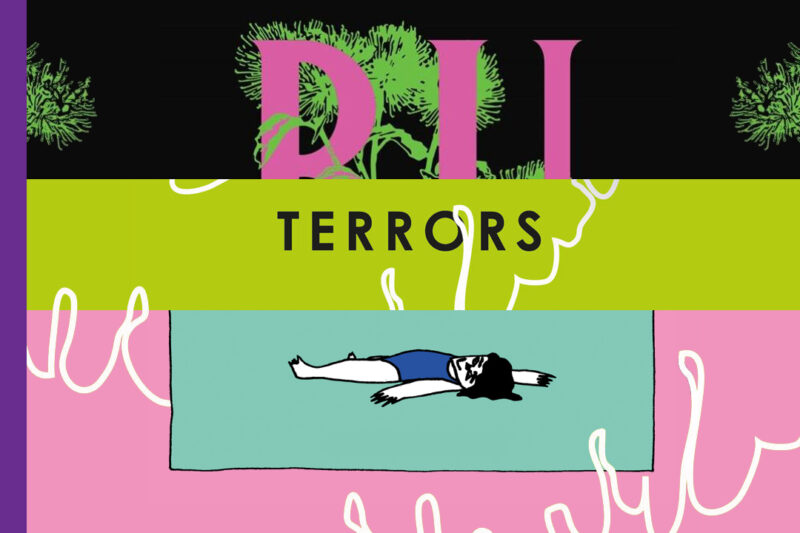

Inside the Giant Fish (Maamoul Press, 2022)

ISBN: 979-8-98718-620-6 | 60 pp | $16.95 USD | BUY Here

What struck me immediately about Rawand Issa’s Inside the Giant Fish — and compelled me to sidle over to the Maamoul Press table amid the bustle of the Detroit Zine Fest earlier this year — was the graphic novel’s colour palette, which is on full display on its cover. At the centre of the cover, a harsh and ominous hue rather like international orange burns the sky, bordered by a soft, wistful shade of cotton candy pink plucked straight from childhood. The sea, which is thematically the focus of the graphic novel, is here represented as only a narrow strip of colour that lies somewhere between ultramarine’s lapis lazuli shade prized by artists for millennia and a more modern version of elegance found in Pantone Classic Blue. The beach sand on which the nameless child protagonist happily sprawls is seafoam green. Over this whole, ostensibly cheerful scene, a humpback whale floats like a melancholy cloud.

The odd but compelling juxtapositions here in colour and content allude to the complexity of what’s in store once you open the book. International forces will fall heavily upon a young girl’s life. The sea that gleams gem-bright in the narrator’s memory nevertheless recedes farther and farther back into the history of her life. Above it all, Jonah’s notorious whale looms, a majestic but not wholly scrutable metaphor.

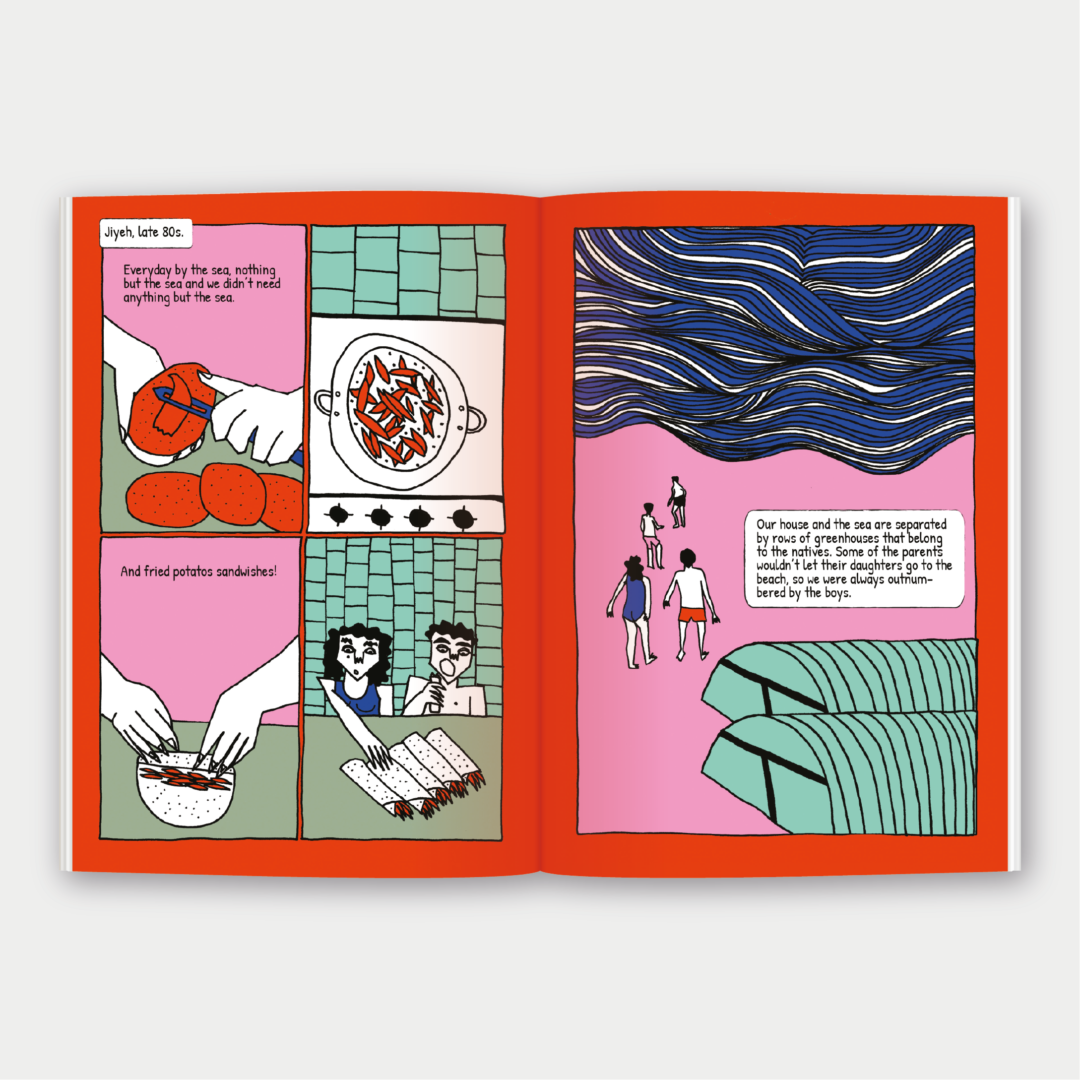

Inside the Giant Fish takes as its starting point the closure of the public beaches of Jiyeh, Lebanon in the 1990s to make way for pricey resorts, and the book examines various social forces that enabled this to occur with little protest from the locals. The end of the civil war brought hard economic times for the farming families who live near the beaches, and most people seem to be too exhausted by the daily struggle for necessities to put up a fight over leisure. As the narrator explains, “I always felt that the 80’s generation in Lebanon was raised on defeat. Our parents had lived through a series of wars, so they raised us to be grateful for the most basic of things.”

It isn’t until the book’s second section that Issa offers us a true glimpse of the narrator’s fond memories of an early youth spent frolicking on the public beaches, and it is here we start to get a true sense of all that has been taken from the narrator and her community.

The graphic novel then leaps ahead chronologically, offering a brief scene of the narrator on Port Stanley beach in Ontario. In contrast to the almost painfully bright colours of Jiyeh, Port Stanley is rendered in underwhelming black-and-white monochrome.

From there, Inside the Giant Fish weaves the narrator’s memories of her time in Jiyeh before the beaches were closed, the time after they were closed and her time in Canada. When asked by an Ontario yoga instructor to picture herself in a happy place, the narrator thinks of Jiyeh, but the memory is tinged with sorrow. The narrator feels that the pain in her joints, the reason why she is doing yoga in the first place, would be cured if she could simply go back to the seaside — an impossible return. It brings to mind that wonderful Welsh word, hiraeth, which connotes a homesickness for a particular combination of time, place and people that no longer exists. Inside the Giant Fish does an excellent job of pairing clear, straightforward depictions of social life with more abstract, nebulous representations of the murkiness of interior life, and the ending of the book, which I won’t spoil, offers a particularly gorgeous and affecting page spread.

I’d like to close this review unconventionally, with a recommendation that, if you’re interested in further reflections on Inside the Giant Fish, check out Chris Burkhalter’s exceptionally comprehensive review in The Comics Journal.

Jim Johnstone

The King of Terrors (Coach House Books, 2023)

ISBN: 978-1-55245-470-1 | 96 pp | $22.95 CAD | BUY Here

Jim Johnstone’s latest poetry collection, The King of Terrors, follows closely on the heels of his previous collection, Infinity Network, coming out just one year after its forerunner. If you’ve read both, it’s tempting, or perhaps inevitable, to compare them. The differences are immediately apparent.

While Infinity Network has an ultramodern title, The King of Terrors opts for a moniker that hearkens back to the book of Job. In chapter 18, verse 14, Bildad the Shuhite says (among other things): “His confidence shall be rooted out of his tabernacle, and it shall bring him to the king of terrors,” wherein the king of terrors is typically interpreted as an epithet for death. The phrase was famously used by Henry Scott Holland in a London sermon in the early twentieth century following the death of King Edward VII (and a portion of that sermon takes its place as the sole epigraph of Johnstone’s collection). The phrase was also used by John Adams in the nineteenth century as a descriptor for smallpox. In these old iterations of the phrase, “the king of terrors” refers to a figure that evokes terror in others.

In Johnstone’s book, the significance of the phrase is just as universal, but the meaning of it is subverted. Let’s walk through its uses. As a book title, “the king of terrors” might signify exactly the same thing it did in its historic contexts — the way the spectre of death looms over, and eventually overpowers, us all (except insofar as we are saved by the grace of God, etc.). That would be a perfectly sensible reading here too, considering Johnstone’s book is an extended meditation on mortality, with the poet reflecting on his own brain tumour diagnosis. But we must go on.

The phrase appears again as the title of a poem early in the collection. That poem reads, in part:

First there was fear.

[…]

Fear of the body, the body bag, bodies zipped and dragged

from home.

[…]

Fear as king,

as crown, as the rush to subsume the twilight of the valleys.

[…]

Fear running free.

(We should stop for a moment here to admire Johnstone’s mastery of internal rhyme (bag / dragged) , of consonance (king / crown) and assonance (fear / free), of rhythm used to emphatic effect. Okay, we can continue now.)

There is a great deal of ambiguity in this poem, and the way it moves through images is purposeful and directed. The associations are typical at first. Fear is linked to injury, to death. Later, though, fear is associated with symbols of power, and later still with the entire abstraction of freedom. Is death, that which strikes fear, really the “king of terrors” here? Or is it the afflicted speaker, patiently abiding his fears, who emerges the true conqueror? Johnstone is too subtle a poet to directly ask this question, never mind definitively answer it, but he makes it impossible for a reader not to ask it of themselves.

That’s a curious trick Johnstone plays, too. Unlike much of his previous work, in which he remained coy about the extent to which the content of the poems was autobiographical, The King of Terrors is forthrightly framed as a collection about his brain tumour diagnosis and the dread that naturally attends it. There are the expected deeply personal admissions, as for instance the halting lines of ‘Slice-Selective Excitation (Brain Scans 1–5)’: “I / apologize / for / the / times / I’m / not / myself.” Here we are witness to a poignant longing for a former self that seems out of reach.

There are also poems that explicitly name his wife Erica, like ‘Invitation (Set to Summer Radio), and poems written for friends and colleagues, like ‘Literally “Former, Elder”’ for poet Michael Prior and poems like ‘Future Ghost,’ which refer to Anstruther Lake, after which Johnstone’s own chapbook press and poetry imprint with Palimpsest Press are named. All of this personal data is laid down amid a context that will be eminently familiar to the contemporary reader: the COVID-19 pandemic. (You recall how the phrase “the king of terrors” was used to refer to another outbreak, namely smallpox? Well, I would hazard to guess that is not mere coincidence.)

And yet. The collection ends (spoiler alert), with this playful, slightly maddening, juxtaposition:

I’m a liar.

I’m a lyre.

Even when he is ostensibly not hiding behind the poetic veil of ‘the speaker,’ it seems there are still more veils between us and Johnstone. The ambivalence of wordplay, for one. A lyre, of course, was famously used in ancient Greece as an accompaniment to lyric poetry. Lying, Johnstone seems to cheekily suggest, might be the modern accompaniment to verse. A bold pronouncement in a purportedly confessional-style collection. But this is precisely what makes Johnstone’s work such a treat for us humble reviewers. We never need to look too hard to find some objet d’art in his work to fixate on. Now, for instance, I could go on with several more observations about The King of Terrors, but I won’t. It’s your turn to go scavenging.