USEREVIEW 139: Radio Waves

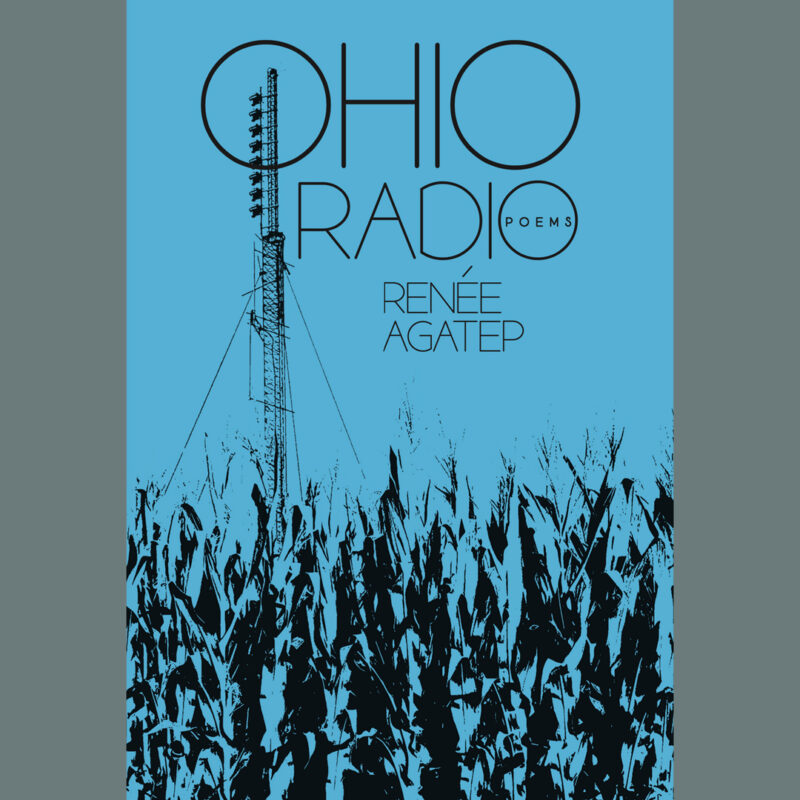

Jade Wallace surfs the waves of sound and sea that crash upon the shores of Renée Agatep‘s latest chapbook Ohio Radio (Wolfson Press, 2023).

ISBN: 978-1-95006-615-5 | 64 pp | $15USD | BUY Here

#CAROUSELreviews

#USEREVIEWEDNESDAY

One experiences duality listening to the radio these days. There’s something quaint about it now — maybe not old-fashioned but running a little behind the times. Its continued existence is a gesture of polite rebellion against the impersonality of streaming services.

And yet, despite being a bit of a relic, radio is simultaneously more immediate than the alternatives. Sometimes live, sometimes pre-recorded, but always situating itself clearly. It tells you when and where it’s coming from. A host addresses you, the listener, and you respond, internally perhaps, or aloud if you’re in that kind of mood, and there’s a possibility for synchronicty that simply doesn’t exist on an infinite playlist.

This is what Renée Agatep’s latest chapbook, Ohio Radio, is like. It’s a voice that’s routed through the past to speak to the present. It takes the indirect path, the backroads, on the way to the airport, and tells you all about the sights along the way while you ride along like a child in the backseat.

More concretely, Ohio Radio is ostensibly about Agatep’s youth in rural Ohio, juxtaposed with scenes from her post-flight adult life in a place utterly unlike the one she grew up in. However, as Agatep makes clear in the collection’s opening poem, she is never as far away from her home state as she supposes. “Woke up today / above a banana field,” she writes, but it only reminds her of the fields of childhood, “green / as alfalfa.” She ends the poem on an ambivalent note that rings with both nostalgia and melancholy: “wonder if I’ll ever leave Ohio.”

Wading further into the text, we begin to get a sense of the source of that melancholy. Agatep’s Ohio “ain’t Norman Rockwell.” It’s a place without a train station “‘cause the trains don’t carry people.” A place populated by “a chain of white paper dolls holding unremarkable hands.” Worse still, our speaker laments, “I don’t belong to any mother here, no one looks out slapping metal screen doors for my arrival.”

Even the titular radio is no comfort, no emissary from a wider world, just “the same shit over and over […] spiraling down into the dark heart of it all.” Those who’ve been stuck listening to small-town radio know exactly what Agatep means. What she dreams of is “to pack and take off, to leave, hell anything but to remain.” But of course we already know she’s not getting out, not really, not completely, so we wander deeper into the dark heart of the text, making our way toward we know not what, hoping to come to an understanding of why Ohio is so hard to leave behind.

What soon becomes clear, however, is that even the speaker isn’t sure why she can’t seem to shake her ghosts. In ‘Recreating Mother in an Ohio Strip Club Parking Lot,’ Agatep tries to imagine, or empathize with, her absentee mother, wanting to “know everything / about the years before lithium,” wanting to “know what drove her / to this godforsaken place” and to “take her back East.” Later, in ‘If Grief Had a Colour,’ the poet says to an unnamed ‘you,’ “I could go to Kentucky, to the mountain, find your name, leave you flowers, wild chicory and violet.” Both of these poems frame departure as a kind of salvation. Place becomes the scapegoat for what’s troubling the speaker, but the poems cleverly allow the reader to see past that wishful thinking. Of course Ohio’s not an innocent bystander. There are, as Agatep has already told us, various factors that make it a difficult place to live. But Ohio alone is not the sower of misery here.

Other sowers include the speaker’s father who “never needed reasons” to handcuff the speaker’s sister. The “tumor wrapped around Greg’s neck / like a sea urchin.” The poverty that needs a free school lunch. But those sufferings? Well they’re everywhere. Not just in rural Ohio. That’s why the poem ‘Those Mysterious Extra Shoelace Holes on Your Sneakers Actually Serve a Brilliant Purpose’ facetiously counsels the reader to use the one’s extra shoelace holes to tie balloons to their feet in order to pulls themselves up by their bootstraps. This isn’t a satirical remedy for Ohio — it’s a satirical remedy for capitalism, which extends much farther than state lines.

There are poems and lines through the collection that are similarly funny. For all its sorrows, Ohio Radio is often charmingly droll. In ‘Poem Instead of a Villanelle,’ Agatep says wryly “i wrote you a real fancy poem about moonsnails, had to google / every other word.” The poem, after various detours, including a tangent about how the speaker learns for the first time what sangria is, ends with hyperbolic but winsome country affect: “id rot in a cornfield if it meant finding out / just one more time. how we aint any good. for eachother [sic].”

Formally and tonally, the poems in Ohio Radio lean in several other decidedly different directions as well. There’s the positively musical, if solemn, quality of ‘Homecoming Blues’: “You ask when I was little, did they find me in the creek / Where the blind riverbed rusts, in the Monongahela bleeds.” There are the sparsely diaristic notes of ‘The Watcher,’ in which the speaker writes of her child: “Midnight / and I can’t stand to see you / sleep.” There are earnest character vignettes like ‘Billy’s Got a Bumper Sticker’ and impatient prose poems like ‘Sing Something We All Know.’ This well-executed array of formal approaches mirrors how thematically holistic Agatep’s portrayal of Ohio really is. In her dexterous poetic hands, the state is beleaguered and joyful, funny and sad, lyrical and banal.

When, halfway through the collection, the speaker complains, “I don’t wanna talk / about Ohio anymore,” it’s rather hard to believe her. Ohio, and her childhood, continue to resurface throughout the succeeding text. Even in the closing poem, ‘The Remedy for Loneliness,’ as the speaker sits by an ocean, with her home state physically and psychically far away, she says to herself, “listen to the waves […] and know they’ve forgotten / your face” and I want to ask her: maybe the ocean forgets who you are, but do the fields of Ohio remember?