“Little That Can Be Done with the Pen …” — a C36 Excerpt

Typewriter art/poetry seems to be having a bright moment — a surge of interest evidenced by several recent mass-market books that survey the medium from different angles. In his article, ‘Little Can Be Done With The Pen Cannot Be Repeated with the Typewriter … ’ CAROUSEL 36 contributor conormcdonnell takes a look at two of the best while exploring 125 years worth of visual-poetic history.

“The paper has to be turned and re-turned, and twisted in a thousand different directions, and each character and letter must strike precisely in the right spot. Often, just as some particular sketch is on the point of completion, a trifling miscalculation, or the accidental depression of the wrong key, will totally ruin it, and the whole thing has to be done over again.”

— Pitman’s Phonetic Journal, October 1898

The typewriter has long signified the writer, the critic, even the intellectual, but do we think of it as a sign of the artist? Many formative works of no little effort and exceptional skill lie anonymous — barely 100 years old — as testimony to the simple beginnings and silent evolution of typewriter art. The typewriter, once an essential tool for formal communication, was quickly reduced by rush of progress and invention to a novelty item, decorative piece and even — as with so many casualties of the digital age — an affectation. Such regression has mapped a gradual loss of function, so how to consider and qualify the significant body of typewriter art created over the last 125 years? How also to nurture the future of a medium that has managed, for the most part, to thrive in comfortable obscurity?

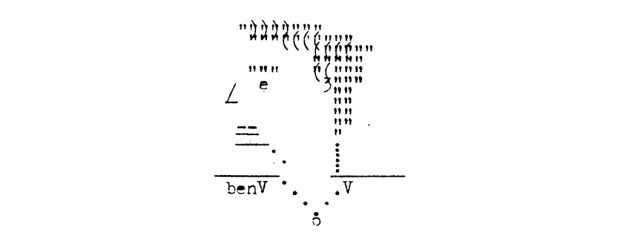

Produced by Remington, the first successful commercial typewriter was made available to the public in 1874. Much like the smart phone the typewriter steered social, cultural and commercial discourse in directions previously unimagined. It placed mass communication in the hands of the individual and was instrumental in female emancipation by ushering women into the workplace. While the word ‘secretary’ may have devolved into a twenty-first century slur, secretarial schools of the 1890s represented a hive of activity in the stirrings of typewriter art. Early attempts to surpass the typewriter’s mono-functionality promoted its potential to embellish with type as stenographers and students were encouraged to submit original pieces for public consumption and competition in popular publications like The Stenographer’s Journal. Flora F. Stacey’s Butterfly (1898) is oft-credited as the oldest surviving record of typewriter art; the surprising effectiveness of what is no more than a collection of dashes and brackets still towers as the most recognizable piece from what is arguably the most enduring figurehead of ‘art-typing’s’ infancy ……………..

:::: Read conormcdonnell‘s full piece in CAROUSEL 36