From the Archive: Anders Nilsen Interview (CAROUSEL 37)

Anders Nilsen is a notable American graphic novelist whose works include Big Questions, Dogs and Water, Don’t Go Where I Can’t Follow, Rage of Poseidon, The End, and others.

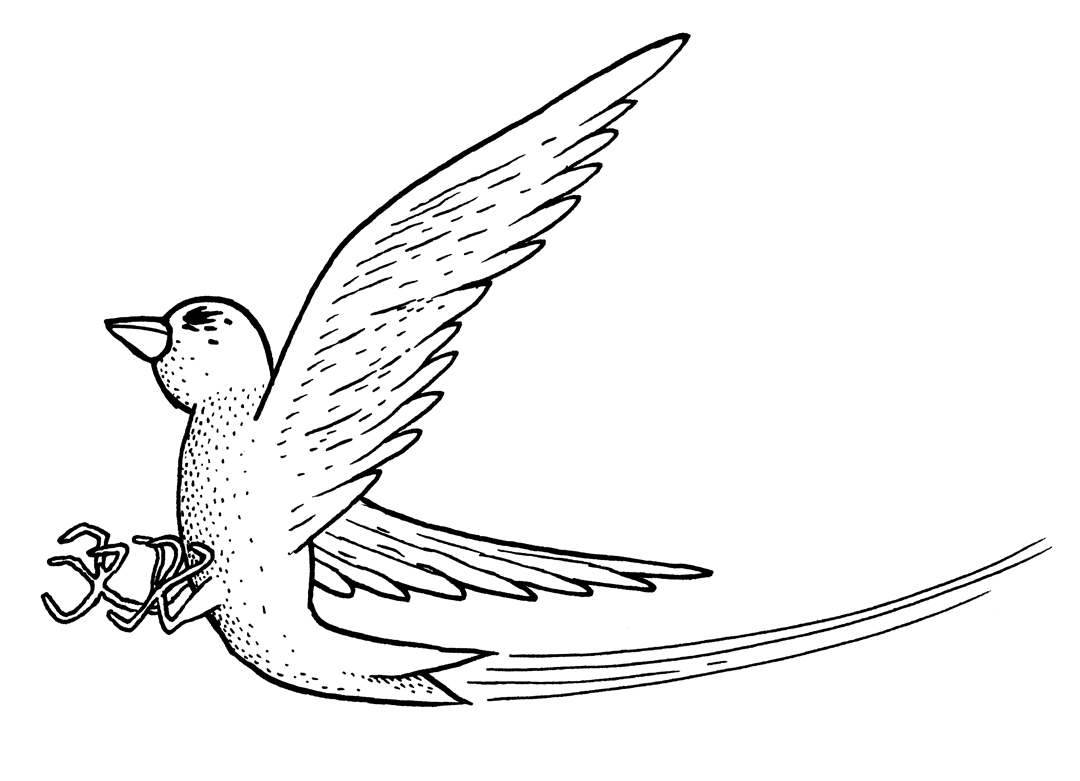

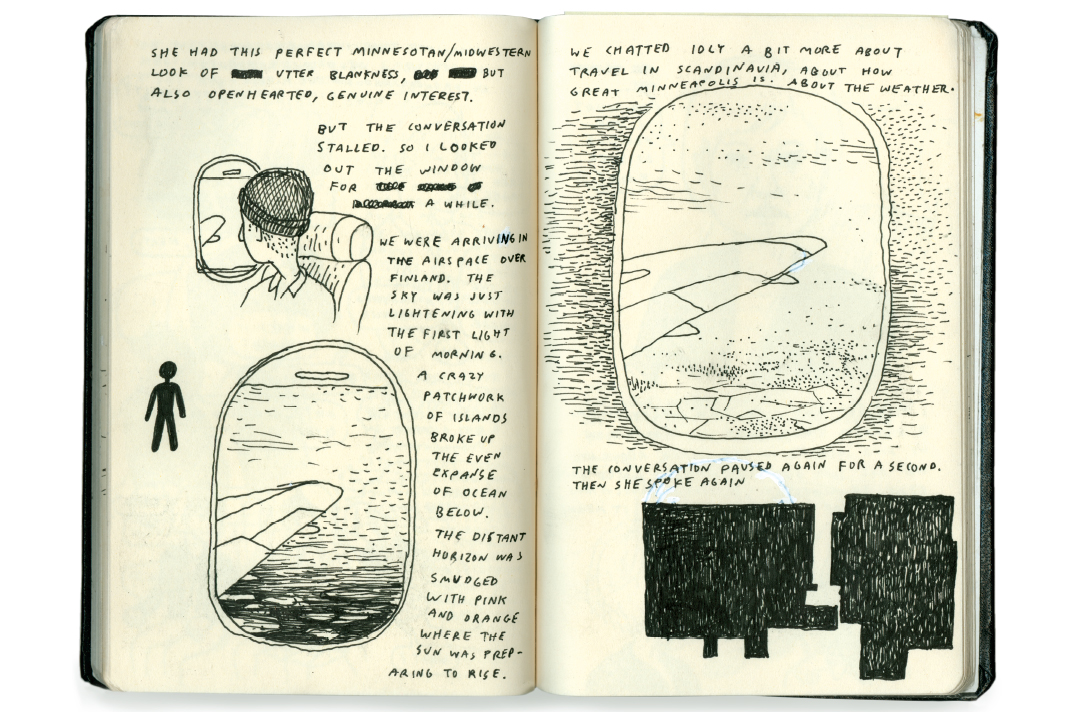

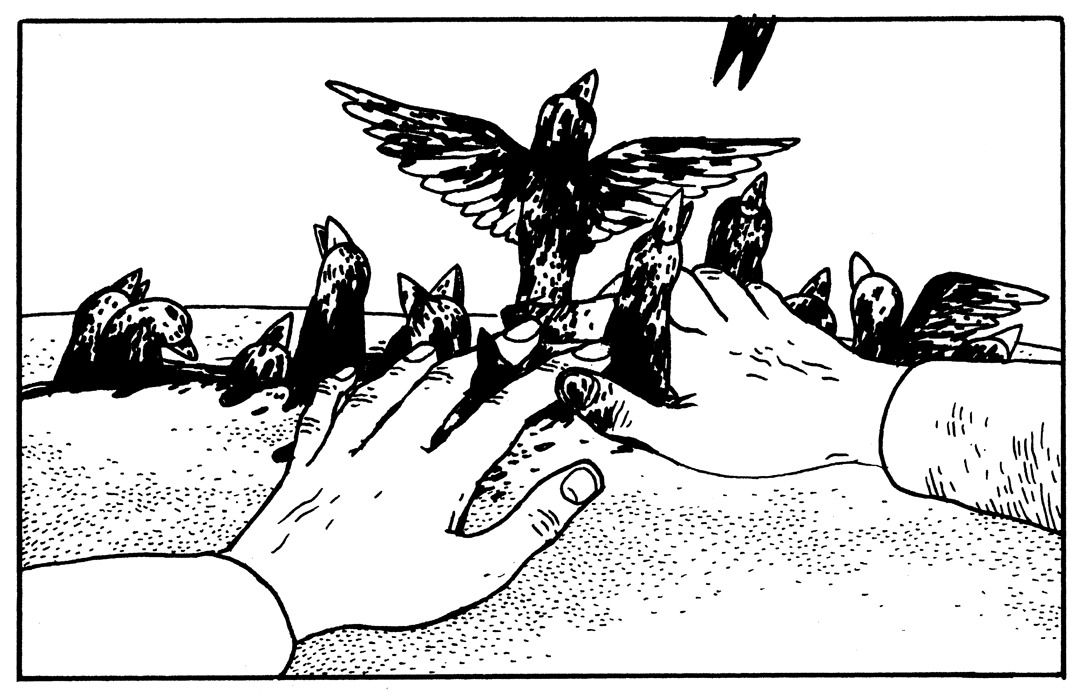

In Poetry is Useless, his latest book, Nilsen redefines the sketchbook format, intermingling elegant, densely detailed renderings of mythical animals, short comics drawn in ink, meditations on religion, and abstract shapes and patterns. This expansive ‘sketchbook-as-graphic-novel’ reveals seven years of Nilsen’s life and musings: it covers a substantial period of his comics career to date, and includes visual references to many of his previous works.

Interview conducted May, 2015

You originally started out exhibiting in the contemporary art world. Does contemporary art inform your current work?

Definitely, although I’m not actively connected to it. When I’m in New York I try to look at the good stuff; I am interested in what is happening in painting. Last time I was in New York I saw a Neo Rausch exhibit — his new show fucking blew my mind, this new work really grabbed me. The pieces were big, monumental; the colours, the light, the atmospherics were really amazing. They felt like dreams, like strange versions of reality.

Are there works of art in other media that inspire or motivate your practice?

Music is the easiest go-to outside of comics. When I first started telling stories and doing comics in the nineties I was thinking a lot about narrative, and how the structure of narrative often mirrors the structure of music; how pieces start out and establish a theme, and then sort of riff on that theme and get more complex; often there will be a climax toward the end, and things calm down. There are interlocking structures to songs. I have sketchbooks where I am trying to make a visual representation of songs and thinking about how that would work in narratives. I’m not particularly musical; I can’t play, I’m useless when it comes to instruments. I was in a band for a minute as a singer.

Are there novelists that inspire you?

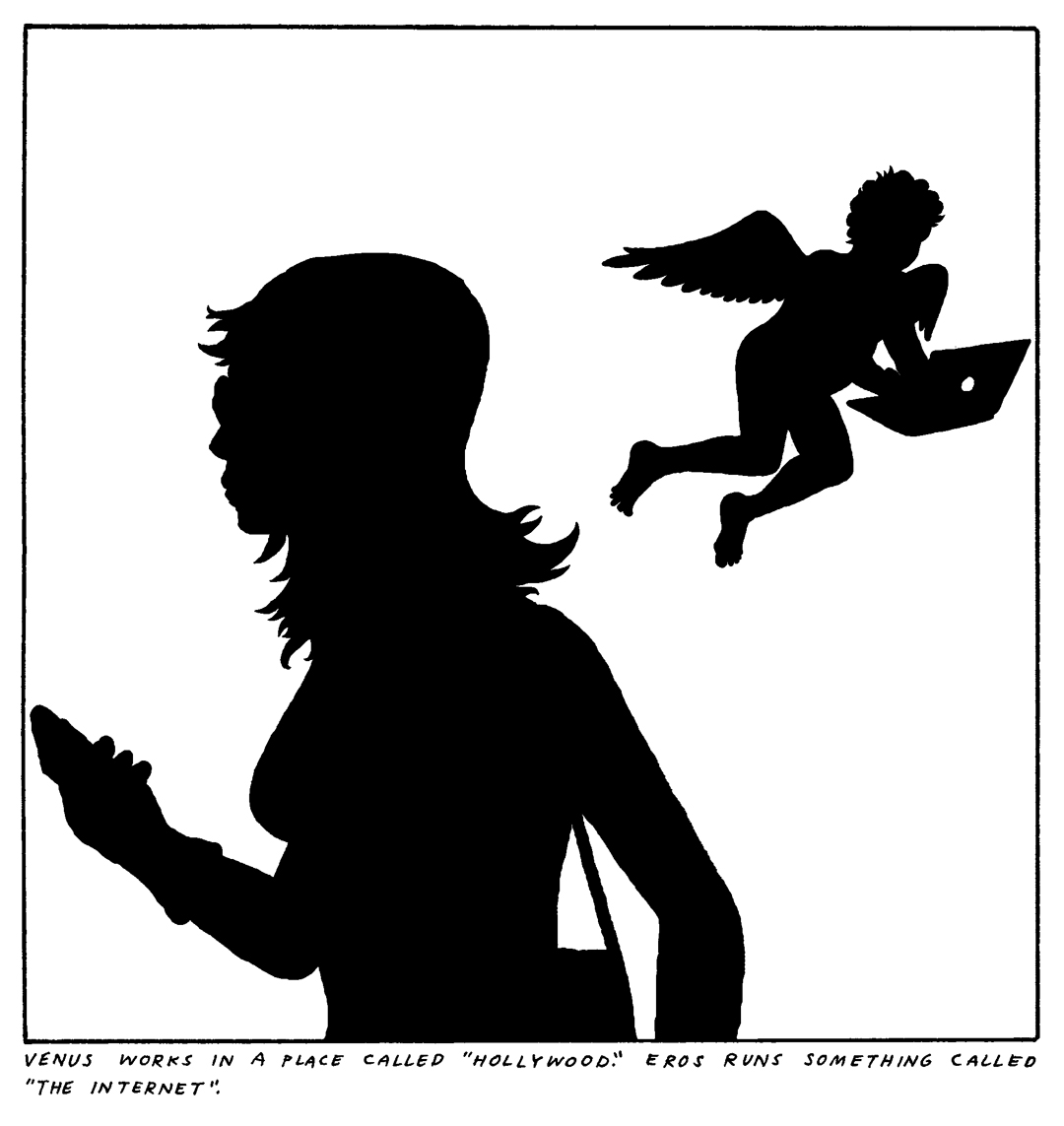

I actually don’t read much fiction anymore, but there were some books that were important to me early on. Pär Lagerkvist, a Norwegian novelist, did these heavily allegorical, existential novels in the fifties and sixties where he was also dealing with religious subject matter. He did a pair of books about this character Ahasuerus, who is the wandering Jew. When Jesus was dragging his cross through the streets, he asked this guy for water; the guy refused to give him water so Jesus cursed him to never die, to walk the earth. Lagerkvist did two books about this guy, far far in the future, still wandering around. He won a Nobel Prize at some point. There is also a C.S. Lewis book called Till We Have Faces: A Myth Retold (1956) which is a retelling of Cupid and Psyche. I think it was one of the last books he wrote. Most of his writing is enthusiastic Christian allegory, this one is much more full of doubt. It is very dark. That book meant a lot to me for sure.

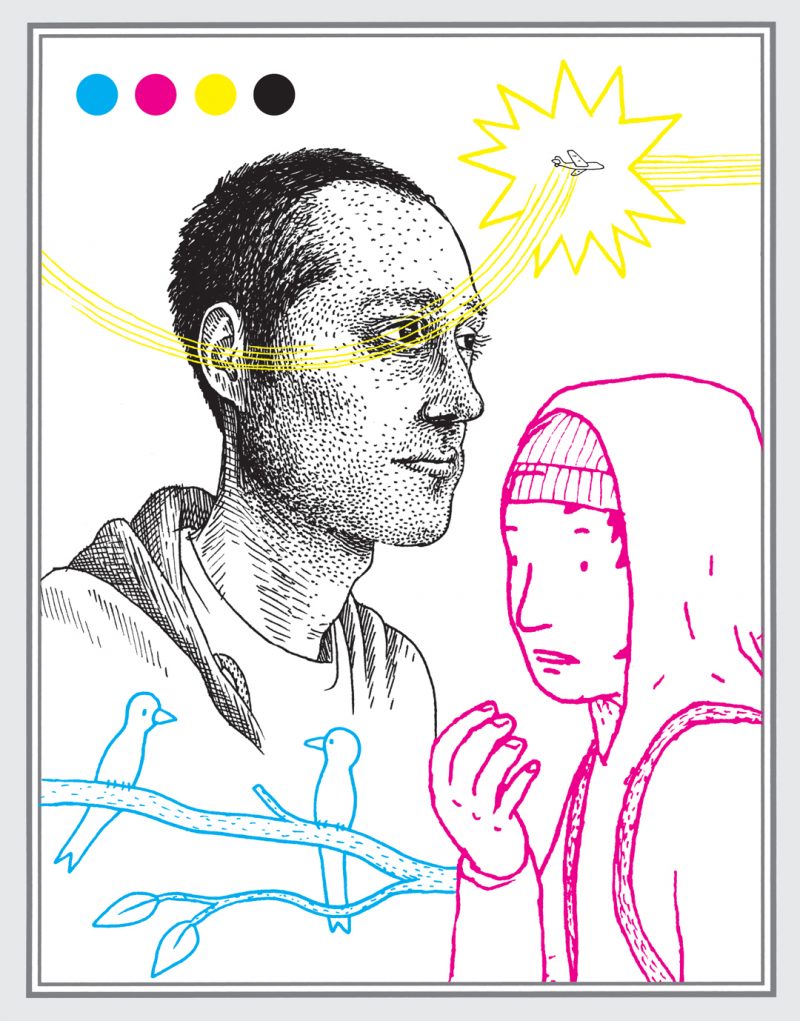

What about in terms of drawing? I was looking at this here, and was reminded of Albrecht Dürer, his ‘Great Piece of Turf/Das große Rasenstück’ study (1503). Do you have a swipe file somewhere?

Honestly, Dürer is probably the person I’ve done the most copies of — more than anybody else. In the new sketchbook, Poetry is Useless, there are several studies after Dürer. The other things I go back to are proto-Renaissance artists like Fra Angelico, Giotto and Piero della Francesca. When I was just beginning to get serious about comics, I took a trip to Italy (in 1999) and went to see all that stuff.

What qualities of those paintings grab you?

They are basically cartoons. At that point, they didn’t care as much about anatomy or perspective or all those things that come later and get really important. They didn’t care about lighting, it is just form and colour — they were making these iconic panels. If you go to the Arena Chapel in Padua, painted by Giotto, on one side is a giant ‘comic’ about the life of the Virgin Mary and on the other side is one about the life of Christ, both told in panels: this happened and then this happened. They are iconic and deeply symbolic. They believed in the stuff they were painting. They were trying to depict their understanding of the nature of the world at its most basic level.

Would you say you have a similar ambition with your work?

Totally. I am an atheist, I don’t believe that stuff; but I’m trying to do the same thing. I want to talk about what the world is, why we are the way we are, and how we should all conduct our lives and be with each other.

Your longer narrative works read like immense allegories, I see symbols in everything. The stories feel dreamlike; they take place in a dream state.

Dreams are super important to me. One thing I wanted to say about allegory is that I am interested in stuff that is symbolic or feels symbolic but maybe isn’t. Dreams operate that way. While you are asleep you have these dreams, these intense experiences that feel extremely meaningful — but when you wake up you can’t even really describe what you saw or felt or did. I’m interested in things that feel meaningful when it is impossible to know why. Or allegories where there is symbolism that doesn’t go anywhere. I feel like as humans, part of what we do is make meaning out of everything. We imbue everything around us with meaning. It doesn’t actually mean there is meaning present, but that is what our brains are wired to do. I’m interested in playing with that idea and trying to take the reader on a journey that actually doesn’t go anywhere, to make people more aware of this curious thing we do.

I think it is realistic to accept that most everything is inexplicable in the big picture.

Yes, it is.

In your personal cosmology do you have any symbols that you intentionally re-use to represent things?

There are things that I re-use. I don’t know if they are specifically symbolic. Is it symbolic, or is it evocative in some way that I’m not sure about? I am always working in my sketchbook, doing drawings, and some little thing will capture my attention and demand to get recapitulated, played with again and again. The tire is one of those things; I like the intricate patterns of the tire, but it is also symbolic of man’s absent-minded effect on the world around him. I’ve also been doing these weird cubes that keep showing up, and I’m not sure what the deal is.

Like the cubes in Big Questions. The cube for me is a unit of space, a 3-D pixel.

Yes, early on in Big Questions that was a thing; then I abandoned it and now it has come back in a different way. I’ve been doing these landscapes with coloured cubes. I did one story recently where they figured as a heart that these characters were trying to find — they pull this guys heart out, but it isn’t the right one, so they discard it. Early on the cubes in Big Questions were about the idea that a stack of them represented the components of one’s self. Your memories, your characteristics; if you pull it all apart what do you have left? You have all these pieces but you don’t have a whole anymore. It’s kind of a Buddhist idea. There is no constant self; you can rearrange it and put it back together in different ways. But if you put it together the right way you have a self.

The model of ‘cube-as-a-self’ makes me think of diagrams, which are a core part of your practice. I’m curious to know about how you think of diagrams?

I think diagrams are closely related to comics.

In some way in a diagram there isn’t really time unless it’s specifically about a process.

That is one of the things that I enjoy about diagrams, or at least the way I am interested in playing with them. A diagram is a single image, so there is no time. But as you start labeling things you are suggesting histories of events. So then you are suggesting time; you are investing this single moment with an extra dimension, of time or story.

It’s like you are applying a layer of consciousness to a scene by labeling it. Do you think that consciousness is in the body or out of the body?

I think it is totally in the body. I am not a believer in the soul. It goes back to that Buddhist idea to have consciousness you need to arrange those blocks in exactly the right way. And if you take them apart, it is gone. It’s not like it went somewhere else and now you are not connected to it anymore. We have it. We don’t really understand it. It is just part of the machinery of our brain.

You pull a lot of symbolism from Western culture, Greek myths, Biblical myths; what attracts you to playing with established myths and legends?

We exist in Western culture and those stories, for better or for worse, are the foundational stories that inform the art and the culture that has led us to this place. I think that some people are more familiar with them than others, but you can take those stories and play around with them and people have a pre-existing sense of them. You are using a pre-existing store.

You don’t have to set up the ground work, it’s like a short-cut.

It totally is a short-cut. There are a lot of elements in my work that evolve out of a certain laziness. Laziness is a useful way to achieve efficiency or try to get to directness. That is one thing about these stories. Somebody else already did this whole mythology, wrote the Bible and created a religion and all of this stuff, and I’m taking a couple pieces off the shelf, and they are premade. I can just make a little thing happen. I’m stealing that history. And I’m really interested in tweaking it and playing around with the weird implications of these nonsensical stories. These very powerful and yet absurd stories.

Did you see The Only Lovers Left Alive, the Jim Jarmusch vampire movie with Adam and Eve?

I actually loved that movie. I went with a friend who hated it; I could see why he hated it. There was definitely a pretentiousness to the characters. It was also funny. I don’t know if Jim Jarmusch meant it to be pretentious in a winking “look at how silly this is” way. I’m not sure if he was aware. When Tilda Swinton was packing, showing us all the smart books that she is reading, it was sort of dumb, “Oh, she’s reading Infinite Jest”. But I love that dumbness. That was the first of his films in a while that I really liked.

Do you find you reference film logic or techniques in your storytelling? When you are making comics do you think about movies or scenes from movies?

Yeah, actually Jarmusch’s Dead Man is one of them; it is one of my favourites. That little weird scene where Iggy Pop is wearing a dress and making dinner for people and somebody comes and shoots everybody; one of the guys falls into the fire and there’s this totally pointless shot from directly above of him lying in the fire and all of the logs are splayed out in this halo effect. Totally gratuitous; it has nothing to do with the plot. It doesn’t really mean anything. But it is a very powerful image. I’ve thought about that image.

Do you record your dreams?

I used to more than I do now. Big Questions has a few scenes lifted from my actual dreams. There’s a dream that the pilot is having where he is walking through fetid, gross water and there are all these unhappy, ill birds in cages. Somebody gives him a knife and he is supposed to cut one open, but he doesn’t quite get to it. Then the knife starts bouncing around in his hand — that sequence is based on an actual dream that I had in high school that loomed large for me.

Speaking of powerful images: in one of your works for the Kramer’s Ergot anthologies, you featured prisoners in jumpsuits. That was a pretty heavy image.

There was an angel with a machine gun leading a person in a jumpsuit with a bag over this head who is shackled but is also an angel. That whole War on Terror thing showed up in a few of my drawings; the fucked up shit in that war appeared in my work. I wonder how that image would go over now? Depicting ISIS as angels might be a little hard to handle.

Which comes back to when you were talking about creating symbolic stories that mean a single thing. Like with the Bible: as soon as you attach a single meaning to something, it has a tendency to spiral out of control.

And then on the other side, those stories are great stories. Isaac and Abraham, for example, is a really important story for me. It is totally fucked. If you take it literally it is incomprehensibly awful. Yet it’s a story that gets retold and retold — people have played with it in literature through the centuries, and there is a reason for that. It is a really powerful, weird story.

It subverts the natural order of things, for sake of religion. This thing that you worship and are subservient to commands you to do this thing that is completely unnatural.

I’m interested in it as a story. Most stories can mean different things depending on the cultural context or the time in your life that you are reading it. That story in particular, at a certain point in my life … you know the dream that I was describing earlier was an Isaac and Abraham dream; the pilot’s name in Big Questions is Isaac.

One one level that story is a literal mindfuck, and it’s horribly manipulative. But at a certain point in my life I had that dream, and I started thinking about the bible story. When you dream, all the characters in your dream are ‘you’; even if you dream about your wife or mother, whatever they are doing is manufactured by your brain, so in some way it is reflective of you and your own internal whatever. So if you take that story, Isaac, Abraham and God are all actually different aspects of ‘you’ and the many ways you interact with yourself. It is a very different kind of story when seen in this light: it becomes a story about what’s important and about making really hard choices in the service of something greater than your own life. It also can still be this weird fairy tale about something horrible being done to somebody. That is what I love — it exists as all of those things all at once.

I think of all the characters in Big Questions as being various parts of myself, of the different ways I interact with the world.

For Poetry is Useless, the new journal-comic, how did you approach compiling it — were you trying to create one thing?

I started working in my sketchbooks in a particular way in 2007. I work in my sketchbooks a lot, and I thought it might add up to a book at some point — that eventually I would have accumulated a bunch of interesting stuff. When I first approached Drawn + Quarterly about putting it out as a book, my idea was to just put everything in there, all the good stuff; it would have been about 400 pages. And they were like “No, we can’t do that, it would be a $75 book” — which was good because it meant I had to actually whittle it down. So, space constraints forced a ruthless editing process of the material; we worked it down to 240 pages or something.

Do you really think poetry is useless?

(Laughter) Yes and no. I suppose you could make the arguement that one of the reasons poetry or art is important is precisely because it is useless. There is a whole understanding of the role of art that relies on the fact that it has no function.

I think of the new book as my poetry collection — really short, self-contained pieces. I’ve done graphic novels, graphic memoirs, short story collections; to the extent that there is an equivalent, this is my poetry. Interestingly, poets seem to like the book. I did a reading at a poetry event and people were slightly conflicted, but they liked it. It looks like my event in Chicago is going to be at the Poetry Foundation, and they are going to be reprinting some of the pieces about the uselessness of poetry in Poetry magazine.

You currently teach comics at MCAD in Minneapolis. Is there any essential thing that you make sure your students understand about comics?

The first thing I think of is that students have a hard time leaving room for editing. Comics does not lend itself easily to editing, so it’s not obvious how to do that and it’s really easy to be precious about your page and not want to cut it up, white things out or whatever. Students are often scared to commit anything to the page and once they do they are scared to fuck it up. There was a student who penciled everything out, then had all the text in there, and it was just too dense. It came up in critique a couple of times, and I pushed him pretty hard to allow himself the freedom to edit: to cut the pages up and insert panels and then give the dialogue a little more space and have some pauses. I try to emphasize a lack of preciousness if I can. I talk about my own work and what a mess it is — it’s full of white-out and there’s a lot of cutting and pasting as I work through things. He was a little resistant at first but finally he did it, and it totally helped; his piece ended up being really strong, I thought.

You’re just not going to get it right the first time, generally speaking. There is a sort of improvisational aspect to creating artwork, and an element of discipline: practice, practice, practice. You don’t get good at something unless you do it over and over again. Like you have to fail a thousand times before you can really succeed and get good at something.

That’s pretty valuable advice for all creative practices.

Anders Nilsen Interview

appeared in CAROUSEL 37 (2016) — buy it here