USEREVIEW 137: Beyond Good and Evil, There are Plants

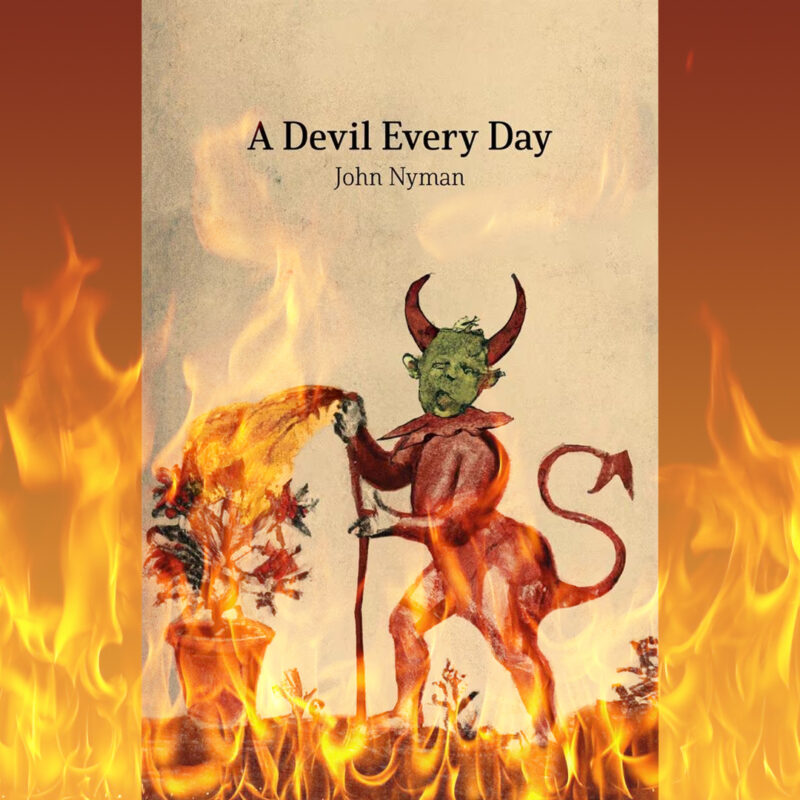

Jade Wallace traces a genealogy of philosophy and flora, in John Nyman‘s latest full-length poetry collection A Devil Every Day (Palimpsest Press, 2023).

ISBN 978-1-990293-46-7 | 88 pp | $19.95 CAD — BUY Here

#CAROUSELreviews

#USEREVIEWEDNESDAY

John Nyman’s sophomore poetry collection A Devil Every Day is a book preoccupied with contemporary incarnations of evil. Several of the poems in the book read like character studies of the Devil, as for instance ‘The Genuine Devil,’ where “The Devil doesn’t want you / to be evil // He wants you to know how,” which seemingly evokes the oft-argued implication of the Old Testament’s Book of Genesis that evil is routed through, or rooted in, an excess of knowledge, or the wrong kind of knowing. But in composite Nyman’s vignettes actually serve to make the Devil more inscrutable, and the nature of evil more nebulous. See for example, ‘The Devil in Person,’ which claims “His pattern’s not abusive / every time.” That line break acts like an ellipsis, placing emphasis on the hedge of “every time.” It’s a statement that appears to offer an answer while only demanding further questions. How often is his pattern abusive? What is his pattern when it’s not abusive? Nyman’s Devil is a character of unresolved paradoxes that might well be contradictions.

Other poems in the book opt not to summon the Devil himself and instead examine less religious signifiers of potential evil. Wikipedia, for example, is made to sound like a kind of hell when Nyman describes it as “the truthless, / bottomless pit of the endlessly freed” in ‘Wikiholing: a hundred open windows.’ In this poem, the devils are misinformation, disinformation and all the other consequences of the failed social quest for a universal epistemological objectivity we can collectively believe in, or at least aspire to. Such concerns about a post-knowledge world would seem to trouble, or problematize, or complicate, if not upend, that common aforementioned Old Testament interpretation of knowledge as potential cause of evil.

I’m not saying that Nyman thinks Wikipedia is the work of the Devil, obviously. I suspect what he has in mind here is Hannah Arendt’s notion of the banality of evil, which he explicitly alludes to in the first and last poems of the collection, and mentions in the notes as well. The concept comes from Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, in which she chronicles the trial of Adolf Eichmann, a high-ranking Nazi official during the Holocaust, who was convicted of war crimes and executed. In her report, Arendt asserts: “[A]s soon as thought tries to engage itself with evil and examine the premises and principles from which it originates, it is frustrated because it finds nothing there. That is the banality of evil.”

This conception of evil may help us to understand what Nyman is getting at in A Devil Every Day. His poetic, quasi-philosophical attempts to come to terms with evil are continually frustrated because the very nature of evil is, perhaps, that it resists understanding. There might be rationale behind evil, but it does not stand up well to scrutiny, and accordingly much evil might be said to result from complacency and compliance, and from failures of critical thought. Within this framework, Wikipedia, with its reliance on knowledge-by-majority rather than a more rigorous and principled system of tests and checks, is not necessarily evil, but one could justifiably look upon it with some suspicion.

Can Nyman’s industrious attentiveness to the nature of evil thus be construed as an attempt to avoid evil? And if this is so, why is Nyman so fixated on this problem?

Concerns about race and racism are certainly one thing on Nyman’s mind. In ‘White Mood,’ he says “sometimes my white mood loses // the wager it’s made on my ancestry, squeezing me / gummy as school glue, the ghost of atrocious // biologies.” On the one hand, the poet is troubled by his own self-admitted whiteness and what it might mean about him, what it suggests about the ideologies he has been socialized into. The problem is not the body itself, but the spectre of potential wrong-headed “biologies” that haunt us with assumptions of knowledge about bodies.

Nyman is seemingly also preoccupied with possible schisms within the self, such as being half-white but also half-Jewish. In ‘Horns,’ Nyman offers a pithy rebuke to the ignorance of certain anti-Semites who, quite ridiculously, allege that Jewish people have horns: “I must be blessed by God to never have to / question the kind of imbecility // A person ½ like me can counter-argue / by pointing at their scalp unthinkingly.” Yet the poem also evinces a self-consciousness the poet has about his own relationship to Jewish identity: “Where I come from, a ½ Jew is an insult / To centring the marginalized.” This fear of being demonized runs in two directions; the speaker is both afraid of being maligned because of his marginalized identity, and afraid of being accused of marginalizing the marginalized by claiming a marginalized identity he might not wholly fit.

Nyman expresses a related anxiety in ‘New Binaries,’ where he admits “I was fearful I’d be outmoded, known / as a binarist when I wasn’t” and then cheekily undercuts this with the follow-up: “it’s simple // as yes or no.” There is obvious irony in this scenario. The alleged binarist experiences angst because he is concerned that non-binarists will binarize him as a binarist. What the poem leaves open is the door through which irony enters the poem. Is Nyman mocking himself, his imagined interlocutors / accusers, a prevailing discourse that entwines them both?

Nyman also alludes to other everyday social ills that are weighing on him and likely contributing to his preoccupation with the nature of evil and whether it is possible to avoid it. In ‘Touch-Me-Not,’ for example, Nyman expresses concerns about capitalism and how it co-opts morality: “humanity folds in my wallet / for point-of-sale virtue signalling.” Throughout the collection, the Devil and evil are either painted in broad strokes, such as in this generic indictment of consumerism, or else they dissolve into dissonance when Nyman tries to examine their minutiae. As hard as it is for Nyman to pinpoint evil, it seems to be even harder for him to outline solutions. In the promisingly titled ‘Four Dreams About Justice,’ the poet imagines a future in which “The cops are unwelcome. The rent has been cancelled. / We’re doggedly woke, ethical, and equitable.” The solutions are as broad and unwieldy as the evils they respond to. Nyman adds — earnestly or impishly, it’s hard to tell — “It’s too bad that wasn’t a real dream, but just / an idea I had unconsciously — irony and all.”

At the end of all this positing, retracting, clarifying, wavering about the nature of evil, what does Nyman leave us with? Plants. One of the book’s epigraphs is a quote from Aristotle’s Metaphysics, in which the philosopher opines that people who cannot distinguish right from wrong, who cannot make moral judgments, are no better than plants. Nyman seems to be asking: well, what’s wrong with being a plant?

“Whoever wrote Beyond Good and Evil / must have had a tree stuck in his brain” Nyman writes in ‘I: to a houseplant.’ This is a reference of course to Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil, a text which suggests, “That which is done out of love always takes place beyond good and evil.” The invocation of Beyond Good and Evil might be read as a subtle hint from Nyman that there are, in fact, things in the world that are not mired in the moralistic binary of good / evil, and that might hold some other, possibly transcendent worth. Within this worldview, the poem begs, what transcendence might plants represent?

In the same poem Nyman, speaking to plants as though they were partners in dialogue, observes that “My species keeps its evil in statistics, / our reptile selves careening aggregate // towards the Devil, while yours accepts it’s mindless / at the level of the individual.” In this exchange, plants represent a nearly Socratic acceptance, if not awareness, of the limits of their knowledge, and a relaxed communal existence that is not moving teleologically toward either good or evil the way humans do, wittingly or not. Similarly, in “A Plant Is Not A Nation,” Nyman critiques the nation-state and praises greenery by contrast: “Unlike a nation, a plant / can stick with its embarrassments enough / to grow more slowly / than the benchmark of accelerating annually.” Plant life, merely by persisting, offers a wordless rebuttal to the unsustainable expansive impulses of imperialism and capitalism.

Perhaps I am over-sentimentalizing Nyman’s account of plants in A Devil Every Day, and perhaps I am doing it because I’ve read a previous poem of his, ‘For My African Violet,’ in which he refers to the plant as a friend and asks the plant to “Be there while I’m wafting the decisions / that bulldozed the fire, // propping each objection up / like a spinning plate.” Plants, in the peace of their flourishing, become a kind of answer, or a balm, or an antidote, or merely something else to think about, for an overactive mind burdened with a thousand moral quandaries that can never quite be satisfactorily resolved.

Two clusters of small, floral visual poems stand at the beginning and end of A Devil Every Day; the first is called ‘Some houseplants, from above’ and the second is called ‘Some more houseplants, from above.’ They guard the book like talismans.