USEREVIEW 136: A Book Carrying an Impossible Weight

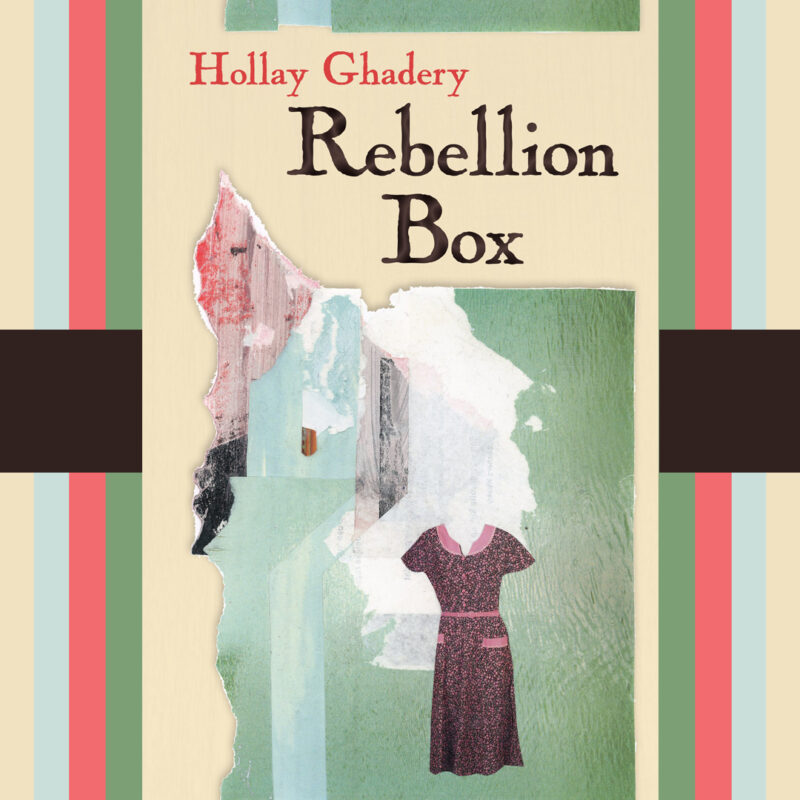

Jade Wallace unpacks the overflowing contents of Hollay Ghadery‘s debut poetry collection Rebellion Box (Radiant Press, 2023).

ISBN: 978-1-98927-491-0 | 80 pp | $20 CAD | BUY Here

#CAROUSELreviews

#USEREVIEWEDNESDAY

When reading a book of poetry, I always like to start with the title. Which sounds silly, because all of us probably see the title of a book before we peruse its contents, but what I mean is that I like to sit with the title, consider what it’s trying to tell me about what’s to come. It’s a road sign preparing me for an unfamiliar path ahead.

The title of Rebellion Box, Hollay Ghadery’s debut poetry collection from Radiant Press, is immediately evocative. What a paradox — a rebellion in a box! But of course I know, because I’ve read (and reviewed) Ghadery’s debut essay collection Fuse (Guernica Editions, 2021) that one of Ghadery’s primary concerns in writing is identity (especially biracial and bicultural identities that defy easy categorization) and how identity in general has a tendency to wrestle its way out of the socially constructed boxes we try to stuff it into. Similarly, Rebellion Box is presented as a collection that “pushes against the limitations of gender roles, race, bodies and minds” in its back cover copy, so this is all beginning to add up. The phrase rebellion box is oxymoronic, but it neatly evokes the way that life transgresses and transcends our stifling efforts at taxonomy.

What is even more interesting, however, is if one looks beyond the readily perceptible implications of the phrase and learns a bit more about its historic significance. Rebellion boxes were small boxes hand-carved from firewood by a group of Loyalists made up of farmers, labourers and tradesmen who were jailed in 1837 on charges of high treason for their rebellion against the British forces who represented “the elitistic system of aristocratic Toryism,” according to Lisa Terech writing for the Oshawa Museum. The rebellion boxes were often inscribed with “messages to loved ones” that ranged tonally from political to religious to sentimental.

In the collection’s title poem, ‘Rebellion Box,’ Ghadery writes explicitly about the eponymous object in a sestina whose speaker is the actual historical figure Joseph Gould, a Loyalist who creates a rebellion box while imprisoned in Fort Henry and sends it along with a letter to the mother of his love interest Mary, as the mores of the time deem it improper for him and Mary to communicate directly with one another. The poem, accordingly, is suffused with John’s muted longing for Mary; Ghadery uses subtly affective lines and the constrained form of the sestina to effectively convey John’s sublimated affection, which he must somehow express without scandalizing Mary’s mother:

You may

remember the summer we cleared your husband’s land. May

came hard and the bees came early. I was stung twice. It hurt,

but Mary was in blue, and it was something else to think about.

As Ghadery explains in an essay for The New Quarterly: “I started to think about how awful it must have felt, to be so young and in love and impotent. To be limited in your ability to even express how you feel because of familial and societal expectations.” It’s easy to see why Ghadery holds a certain affinity for Joseph Gould. Both of them are struggling against social norms in their efforts to convey something deeply personally meaningful. They are both creating their own rebellion boxes — Gould literally carving a box and Ghadery figuratively carving out a literary space in the form of a book — unassuming little vessels that carry within them a spirit of disruption.

In ‘Free Indirect Discourse (for Atefeh Rajabi),’ Ghadery addresses another historical figure, Atefeh Rajabi Sahaaleh, a 16-year-old Iranian girl who was executed by the state for so-called ‘adultery’ and ‘crimes against chastity’ after she was repeatedly abused and taken advantage of by an older man. (A more detailed account is available here.) Ghadery speaks to Atefeh in what can only be described as a heartbreakingly motherly poetic voice that affectionately counsels defiance:

you loved this world so

inhale, no one

can tell you

when you are born

No one and nothing, of course, can truly resurrect Atefeh Rajabi Sahaaleh, and her wrongful execution cannot possibly be righted, but Ghadery does attempt a transcendent memorialization here that tries to offer a kind of figurative rebirth, an attenuated revival. Such a literary afterlife is probably no consolation to a girl who is gone, but its quietly political call to sympathy is a subversive version of consolation for those left behind. This poem, as so many others in the book, reveals Ghadery’s exceptional talent for confronting the reader with disarmingly hefty lines packed into impossibly small containers. The poems of Rebellion Box move persistently toward a freer future while carrying the weight of both grief and laboriously earned wisdom from the past.