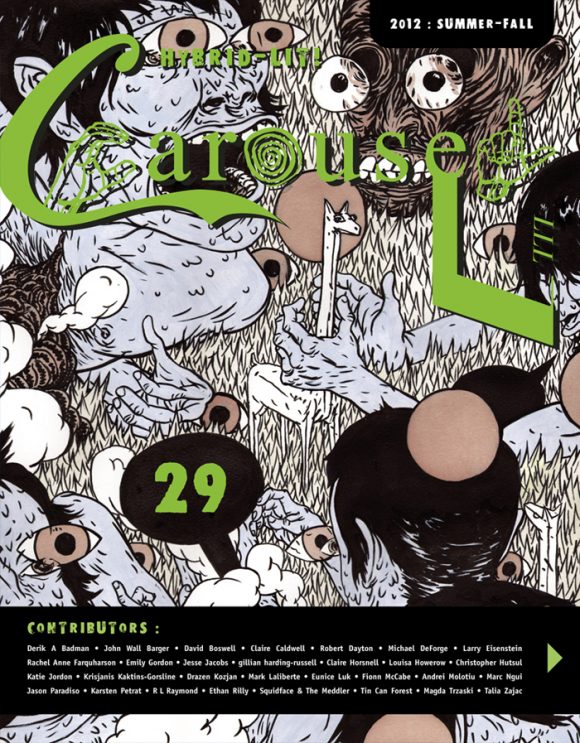

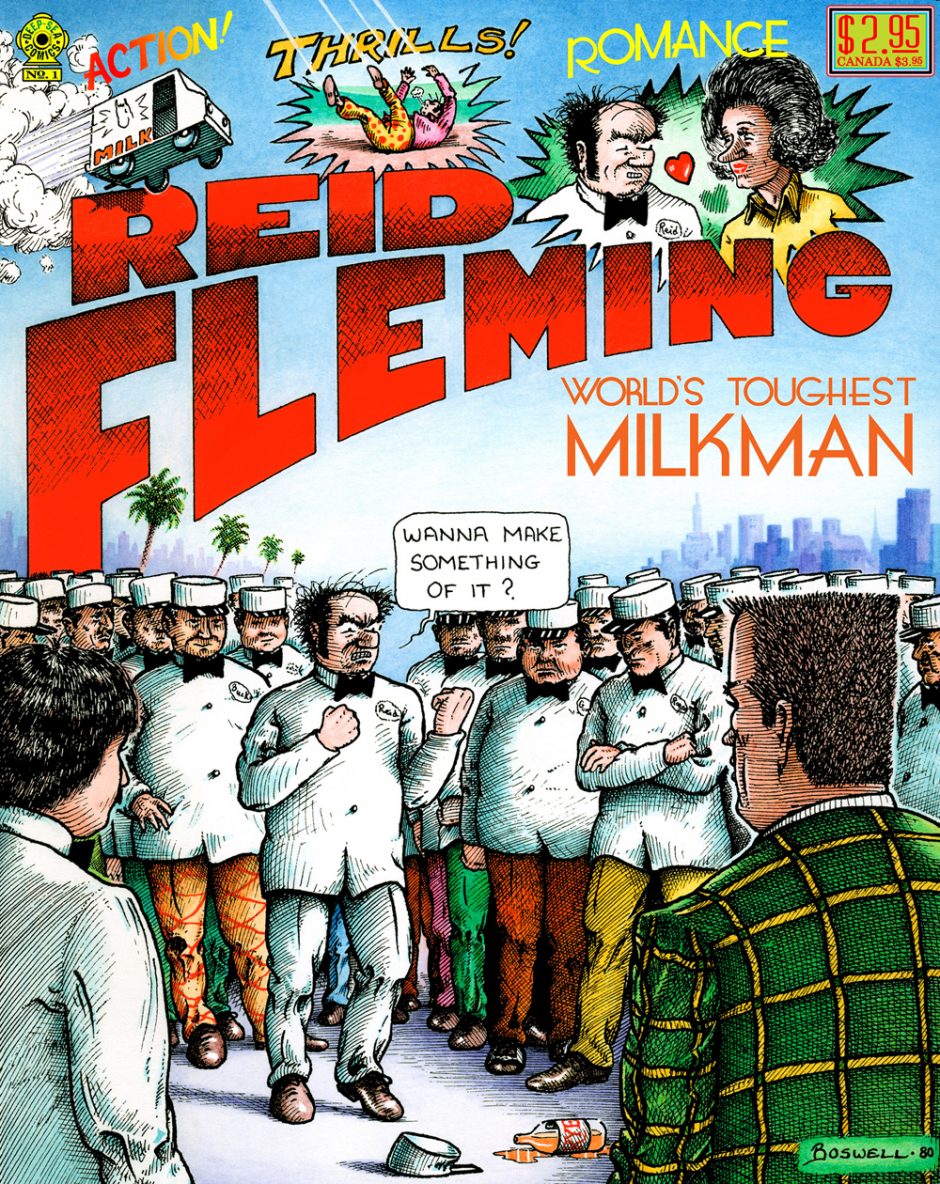

From the Archive: ‘David Boswell: World’s Toughest Cartoonist’ Interview (CAROUSEL 29)

Jack-of-all-trades Robert Dayton has known artist / photographer David Boswell for a few years now, and has been a fan of his comic books for far longer. On the eve of the announcement of Boswell’s induction into the Canadian Cartoonists Hall of Fame, Dayton chatted Bowsell up on the mean streets of Toronto, on a sunny day — read on to find out why he is convinced that Boswell makes the funniest comic books of anybody alive today …

Hello, you must be Robert Dayton.

And you must be David Boswell.

And this must be Toronto.

— We are in Toronto.

And it’s Sunday, May 08, 2011 and it’s Mother’s Day; hello Mom!

And yesterday was Saturday and you were here at the Toronto Comic Arts Festival and were awarded a status of the ‘Giant of the North’ entry into the Hall of Fame as constituted by The Doug Wright Awards.

It’s apparently a lifetime achievement —

“A lifetime of outstanding Canadian cartooning.”

— even though I’m not even dead.

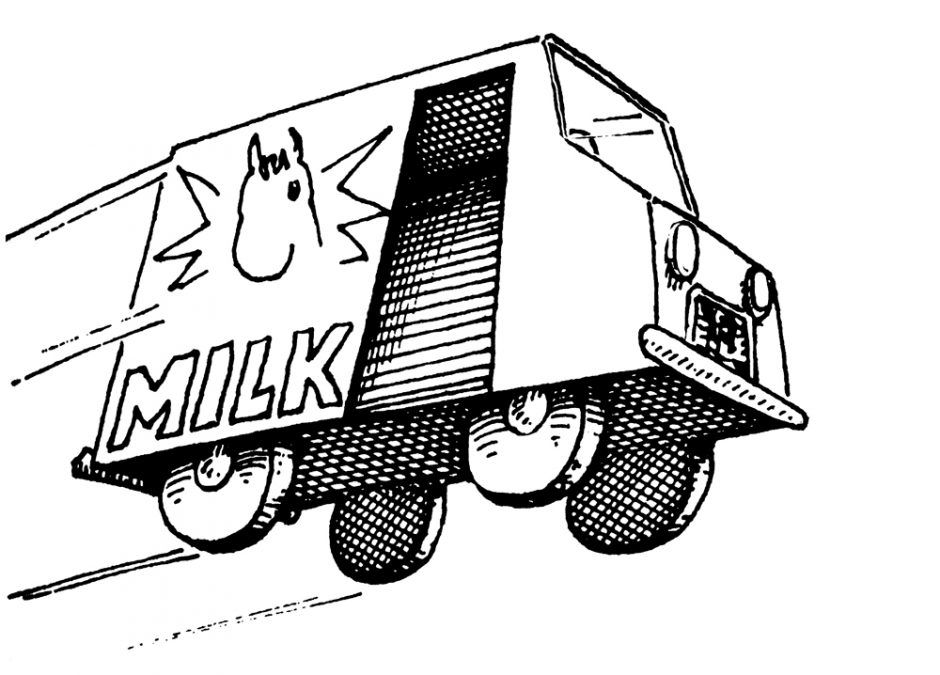

You’re very much alive, working on stuff right now. It’s not like your career’s over just because a massive hardcover collection of Reid Fleming, World’s Toughest Milkman recently came out through IDW.

I am currently completing contents of the second volume. It will be largely constituted of my new graphic novel Another Dawn, which I started in the late ‘90s. The first three parts have come out, there are two more to go. As of today, the fourth part is largely complete; I’m writing and about to start drawing the final and concluding chapter. This last chapter, I should say, is going to rival a Cecil B. DeMille movie in terms of epic grandeur and mass crowd scenes and thrilling action, and I might even put in some Technicolour inserts.

How many pages of brand new material is it?

It’s probably fifty.

It’s been about ten years since you’ve released a new Reid Fleming comic. Why the hiatus?

I took out some time to work on a crossover with Bob Burden, Flaming Carrot and Reid Fleming, World’s Toughest Milkman. It was published by Dark Horse Comics and came out in 2002, and it took way too much time. It kind of turned me off comics for a while because it was not a pleasant task; it was really an ordeal. I don’t want to slag Bob Burden — he’s one of the greats in comics — but it was a very difficult assignment. It was supposed to be done quickly to make some quick cash; it took several years.

It was your first real collaboration, right?

Yes, and I doubt that I’ll ever collaborate again. I must say that when Bob first pitched the idea of collaboration I was rather dubious. It seemed to me that Reid Fleming and Flaming Carrot inhabit completely different universes. They’re not at all similar. Bob did not write a complete script; the last five pages were encapsulated in two sentences — I could never get him to write anything beyond the “battle royale”. Actually, I ended up writing the ending myself and I turned the entire story into a dream of the monkey character.

Ah, the old dream ending!

I thought it worked, and I remember Bob saying, “I don’t remember writing this!” — you didn’t write it!

It’s got some great moments. Christopher Walken is there in all his glory. Do you think he’s ever seen it?

I have no idea. I hope that if he does see it, he knows that we respect and admire him.

You were self-publishing in the ‘90s. And now IDW is putting out these hardcover collections in the era of the graphic novel. How does it feel to return to Reid?

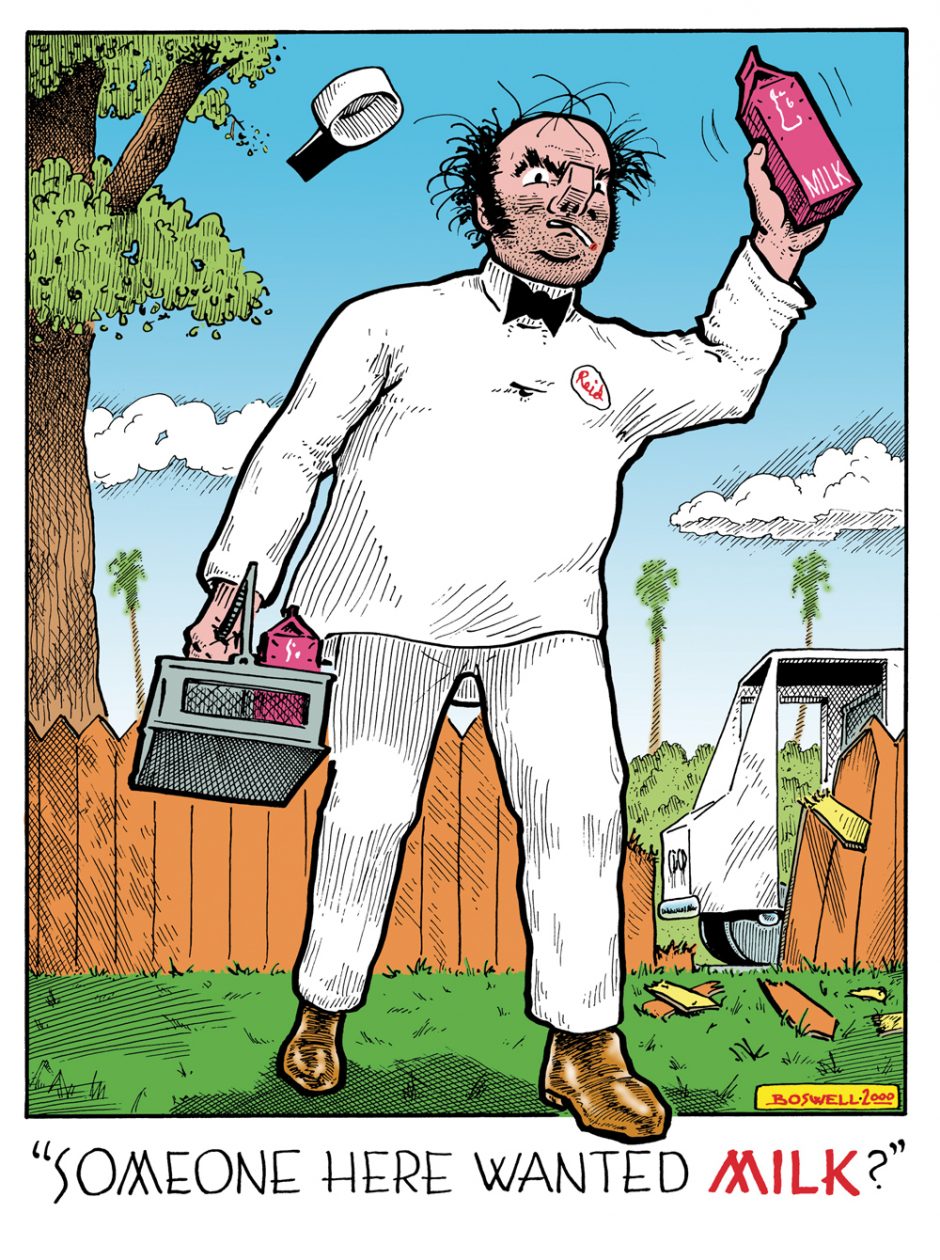

Reid never goes away. He’s like a relative, always there no matter how you feel about him. Also — like some relatives — one doesn’t necessarily choose to be around the guy unless it’s absolutely unavoidable. Once a book is done I have to get away from Reid for a good long while. Some people are exhausting to be around. At the same time, Reid’s my meal-ticket (ha ha), and we have to work together to survive.

As a character, Reid is so aggressive. You don’t have that in you, you don’t seem to be an aggressive person. Where does that aggression come from?

It’s hard to say. I don’t feel myself to be an aggressive person but we all, I think, have at times, moments where we’d like to be able to react in an immediate way. Reid goes for it, he does what we all think of doing but never dare to do. And because I am pulling all the strings, I work it so that he gets away with it. But it’s got to be believable. He does get chased by the police at times.

You make sure that it’s believable, and approach it with a sense of humour. Your jokes are amazing — the set-ups, pacing, comedic timing and punch lines work incredibly well.

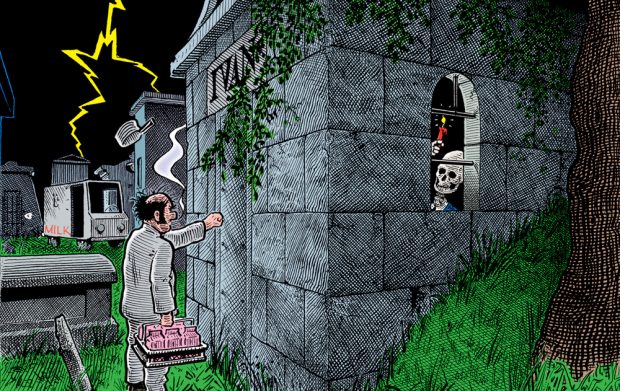

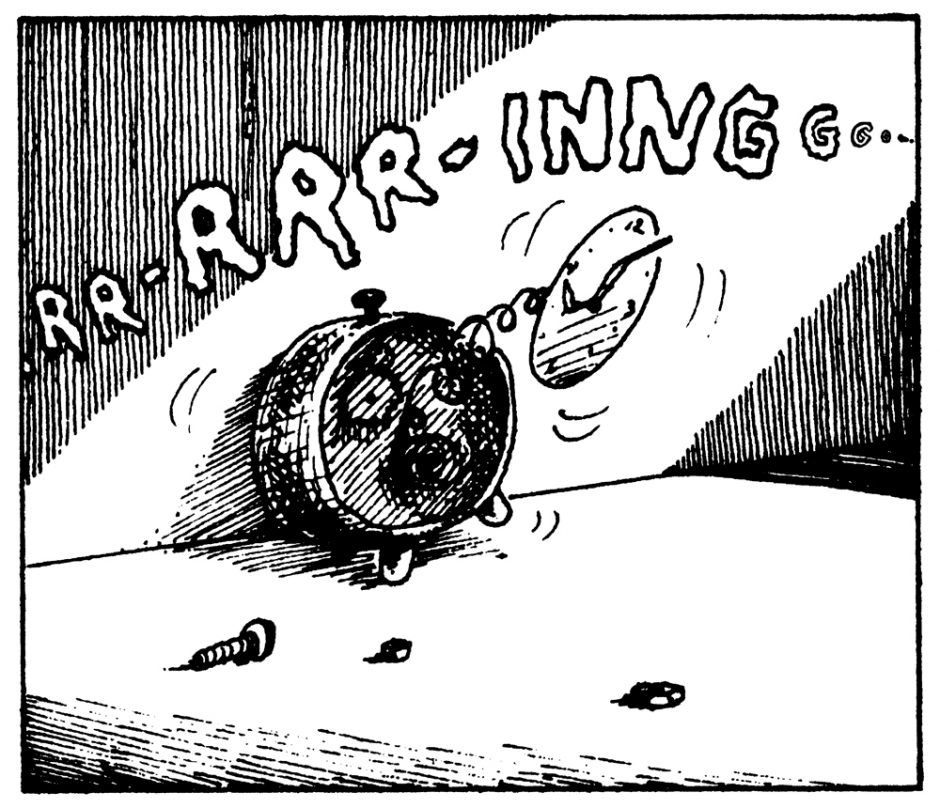

I spend a great deal of time on the writing. For a twenty-six page comic. I’ll typically write one hundred and fifty pages of script or more. Every page is carefully edited 5 or 6 times before it’s done. My job is to make Reid palatable without losing his edge or his capacity to surprise the reader. There’s a lot of traditional corn-ball humour — exploding cigars and the like — mixed in to leaven Reid’s apparent psychopathic tendencies. What I hope people understand is that what Reid is doing is making himself laugh. When he’s beating a guy up for making fun of his milk truck you have to say, “Is he really angry or is he using that as a pretext?” because it’s the absurdity of the response, it’s out of scale. If somebody says, “Hey! Look at the stupid milk truck!”, a normal person would say, “Screw you, buddy!” But instead Reid jumps out of his truck and whales on the guy with his famous windmill punch. And then says, “Tell your friends!” and drives off in a blaze of booze and smoke. That’s completely disproportionate to the provocation.

You see that in your influences. You don’t have a lot of comic book influences, but you have filmic influences with the Marx Brothers. In their films, they’re obviously generating things for their own amusement.

I would say that as much as I love the Marx Brothers — and only really their first five Paramount films — they’re not direct influences in a visual or a story-telling sense. But in a life sense, discovering the Marx Brothers was huge: seeing Horsefeathers (1932), at the age of fourteen changed my life. When you’re fourteen you start to think about what kind of an adult you’re going to have to be. And it all looks pretty bleak. And then suddenly here are the Marx Brothers, grown-ups functioning in the world of grown-ups solely for their own amusement. I guess what got me was the idea that “The Laff” could be the primary focus of your life, and not dreary reality.

What about W.C. Fields?

Discovering W.C. Fields, also at the age of fourteen, was even bigger than discovering the Marx Brothers. As far as influences, Fields is God, definitely major! Of course, Reid Fleming draws from only one aspect of Fields — the cranky misanthrope of popular view. But Fields often played a very different type, the humble family man, trying to make a go of it in traditional ways — jobs and families — and being always on the receiving end of life’s aggravations. There are different Fields’ personae and I like them all.

Speaking of cinema: will there ever be a Reid Fleming movie? It’s been hinted at for years.

I wrote a script for Warner Brothers in 1987, and they own the movie rights. Unfortunately, they’ve got it forever; they won’t let it go, despite many offers over the years. Lots of actors and producers have wanted to make Reid Fleming, World’s Toughest Milkman into a movie. Initially Bobcat Goldthwaite was going to be Reid; Jim Carrey was interested later. Yet they won’t make it without just the right names — it’s a bit frustrating, but you can’t let other people control your happiness. Just accept what’s there and forge ahead.

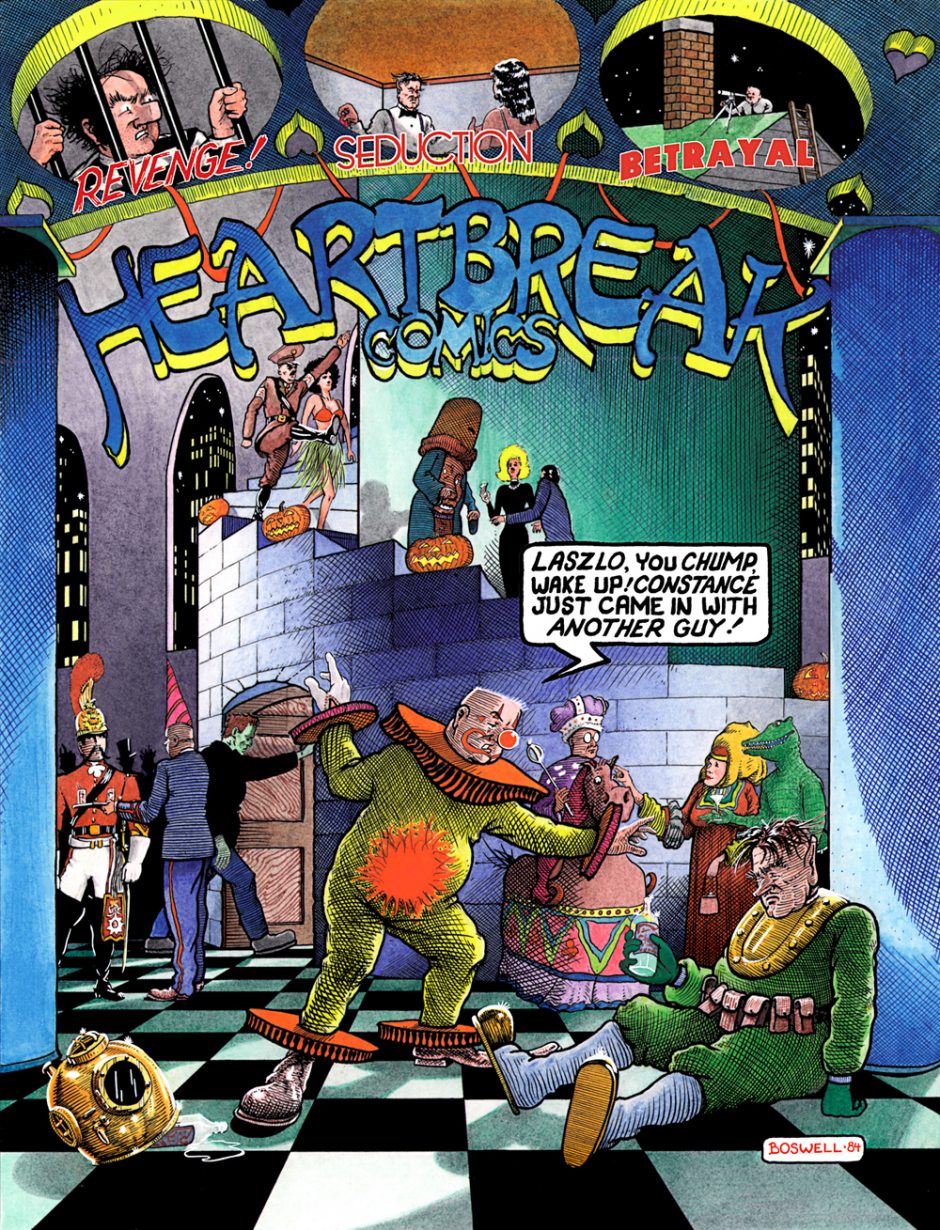

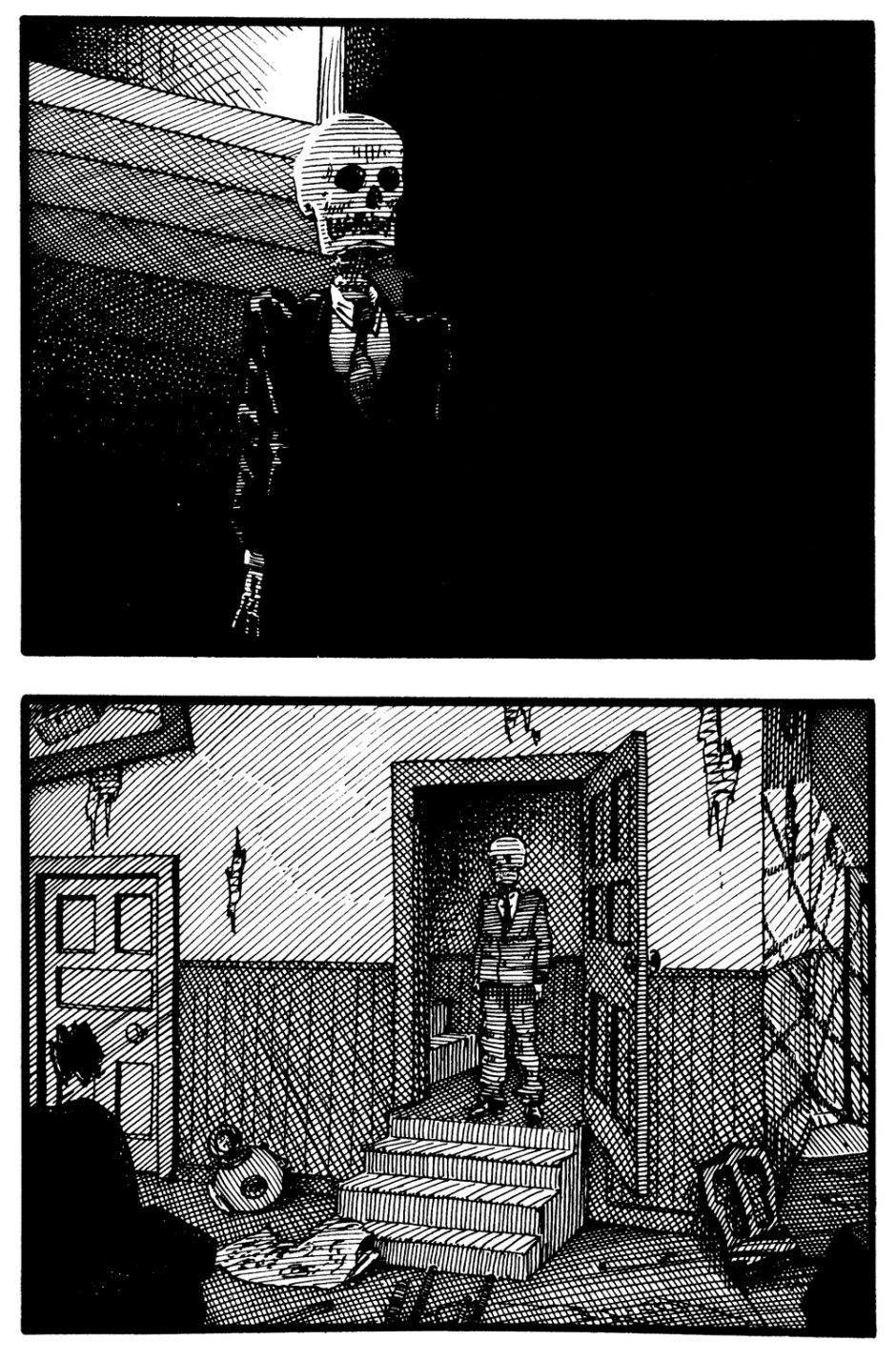

Heart Break Comics seems to share a ‘30s filmic influence, but of a different set — it’s a darker, more melodramatic comic book.

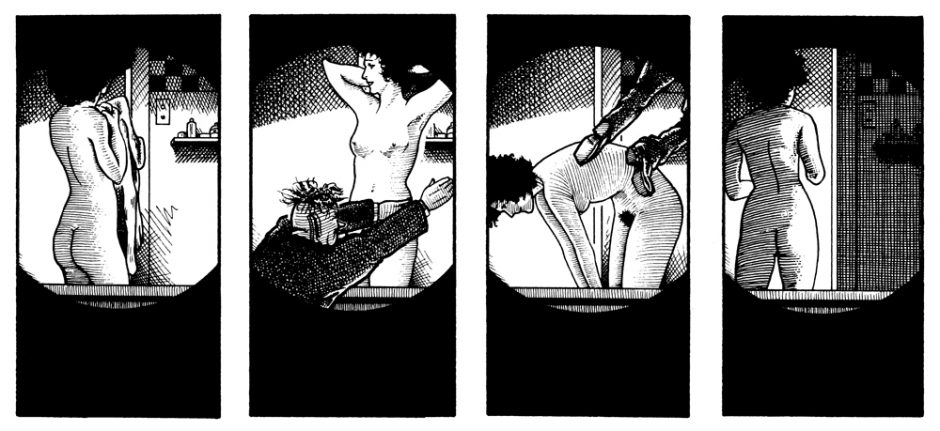

Heart Break Comics is about the love life of a character named Laszlo, who seems to embody the archetype of the suave continental lover seen in films of the early ‘30s. Laszlo’s world visually resembles the world of those black and white films: that’s where he wants to live. Of course, it gets him in trouble because the rest of the world has moved on; his values are shown to be rather out-dated. Technically, I had to figure out how to achieve that look in a comic. Took quite a long time, as it all comes down to cross-hatching, millions of little tiny lines to build up grey values. The phrase “black and white” is so misleading — it’s the grey tones between black and white that determine the picture’s effectiveness. My earliest influences in this regard were not from movies, but the 19th Century engravings of Gustave Doré. I was eleven years old when I made that discovery. Now there is an absolute master of light and shadow and composition. A later influence is Josef von Sternberg, whose films I discovered when I was seventeen. The apex of black and white cinematography, if you ask me, though that is not the only reason I love his films: under the opulent surface there’s a sly sense of humour constantly at work. I hope some of that comes through in Heart Break Comics.

Everything’s heightened in Heart Break Comics, including the stairwells. You use a cinematic flare that, at times, looks German Expressionist.

It’s fun to do. In a movie you’d need to get approval to build large expensive sets, but in a comic your only limitations are time and ability. There’s nobody to say “no”. I started making films when I was fifteen, and went to Sheridan College in Oakville for film school, and found that making films is loads of fun but very, very expensive. Eventually it dawned on me that comics were movies on paper, and the first book was drawn deliberately with all panels the same size so that it would look like a storyboard. I was a late starter as far as comics are concerned. For Heart Break Comics I had to pause after working on it for a year and a half in order to learn architectural perspective. You can’t fake a spiral staircase, which I planned on using for a scene at a masquerade party.

Working on this project for the Georgia Straight was your training ground. What was it like doing comics for a weekly?

Nothing scarier than a weekly deadline and an empty sheet of paper. Heart Break Comics was my first published work (14 July, 1977) and ran for thirty-five weeks. The first 6 or 7 strips were done while I lived in Toronto; later that year I moved out to where the paper was located, in Vancouver.

Reid Fleming, World’s Toughest Milkman was born in Toronto — in my sketchbook — on June 29, 1977, but did not appear in print, in the Georgia Straight, until June, 1978. I was fortunate that the Georgia Straight people were so tolerant. Vents Baumanis, the guy who hired me to provide weekly full-page black and white comics, turned out to have had no authority to hire anybody at all; he was only the advertising manager. But he liked my work and told me to do more. When I got to Vancouver, I met the real boss, publisher Dan McLeod; he still runs the Straight today — very successfully, too. He was a rather taciturn individual, and after our initial meeting he said nothing to me for several weeks, until one day inquiring, “why isn’t Laszlo funny any more?” Heart attack! But he was right — I was having a hard time figuring out what to do with the character of Laszlo, how to sustain an idea. After three months I quit, and went back to photography. Luckily, the Straight’s editor, Bob Mercer, wanted the strip to continue, and managed to get me a raise from the $20 per page I’d been getting previously. So I gave it another try and resumed the life of a cartoonist in May, 1978. Otherwise I wouldn’t be here now!

Reid Fleming is looser than Heart Break Comics, yet because of that architectural skill you are able to make it multi-tiered.

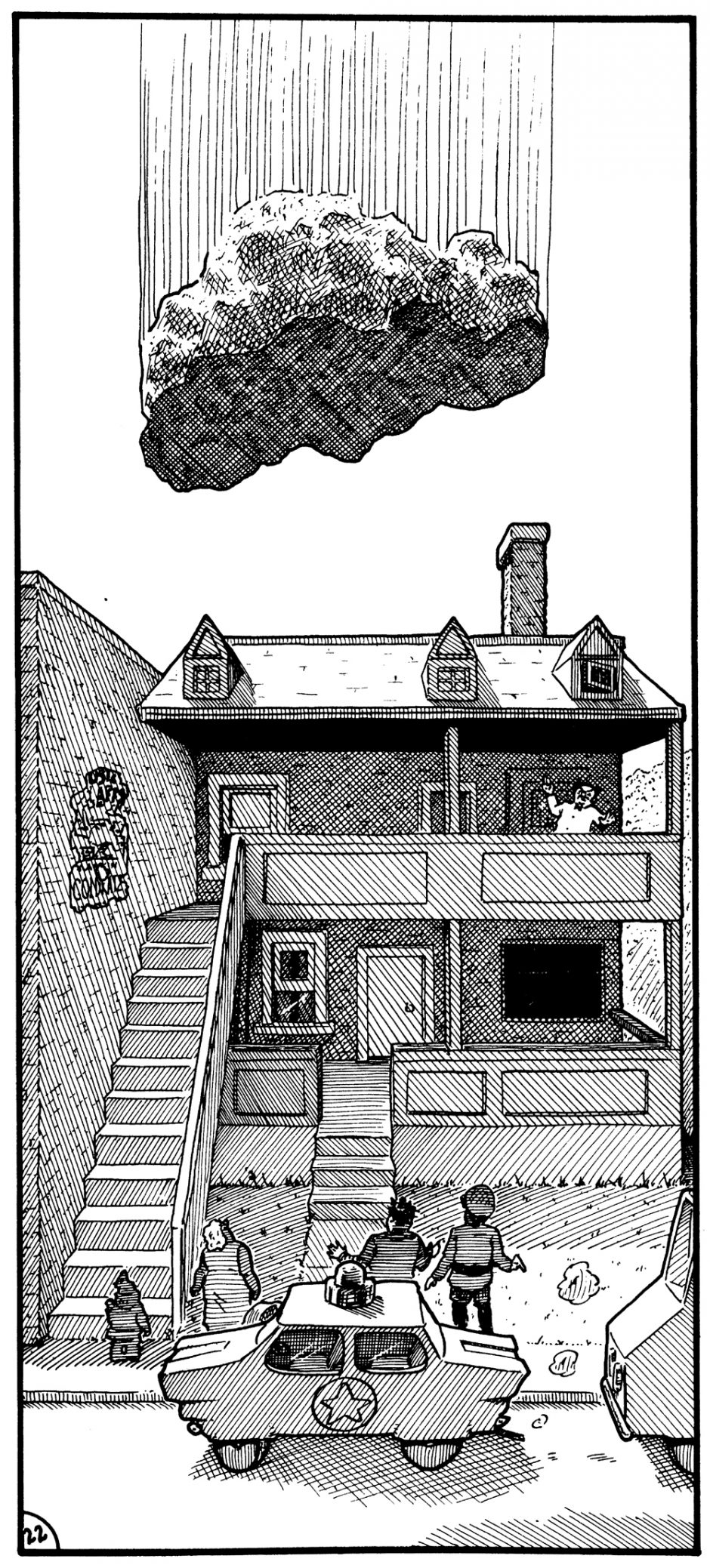

It’s fun to use space for laffs. For instance, at the company where Reid works, Milk, Inc., there’s a subterranean crypt for dead milkmen. To get to the crypt you have to travel vast distances through huge vaults and tunnels and staircases. There’s a flashback sequence coming up in Another Dawn, where Reid’s pal Cooper — aka Captain Coffee — is describing a visit to this crypt and is stuttering and stumbling verbally, while behind him a parade of majestic and gigantic images is going on.

The crypt is there for a purpose. Another Dawn is about what you get after a lifetime spent working. At Milk, Inc., milkmen who work twenty consecutive years are rewarded with a niche in the company crypt, where all the greats are buried. At the time the story takes place, there is only one niche left, and Reid Fleming is determined to get it for himself.

You briefly mentioned an alternate life as a photographer; you’ve taken photos of many famous people, including Leonard Cohen, who has used your images on some of his book covers. Has photography informed your craft as a cartoonist?

Possibly. It’s just about learning to see and how to place things in front of the camera or in your panel in a very clear way. With comics, make it easy for the eye to follow, that’s the first thing — that applies to the lettering and to the action. The eye is moving always from left to right, so lay out your dialogue and stage your action with this left-to-right flow in mind. It’s ideally set it up so it can be easily followed, dialogue and action, right to the end.

Does that inform how you work with panels and compose each page?

In a way. I always work from the old silent movie aspect ratio of 4:3 — I start with that. It’s a starting point and a calculation point for my vanishing points in perspective drawings, all predicated on that aspect ratio. Size varies; some panels need to be big because they’re huge spaces. What’s important is to compose a page that people turn. That bottom right-hand panel — the last one you see on a two-page spread — has always got to be as strong and funny as possible. That one I make strong and suspenseful so that people want to turn that page.

You drew Heart Break Comics at twice the size it was printed and have stated that you’d never do it again because it was so painstaking. What sizing do you normally use?

Normally, it’s done half-up — the art is drawn 150% larger than it’s printed, then reduced by 66.6%; the page I draw is 10” by 15” and gets shot down to comic size, which is about 6” by 9”. In the new book I’ve been switching back and forth between half-up and twice as big for certain pages. I get some very large vistas and they benefit hugely from the extra resolution you get when you draw things big.

What do you draw with mainly?

These days I use a combination of rapidographs and quill pens; I use brushes only for white highlights. In Heart Break Comics you’ll see the little sea anemones in the underwater dream sequence, it’s all done with a triple zero brush and white paint. For mistakes I use Pelican White. It’s a graphic white and one little jar will last you a lifetime. When I started doing comics I didn’t even know that stuff existed! I’d use typewriter white-out, which is horrible and awful; I just didn’t know, I was ignorant.

Let’s talk a bit about lettering. You have a distinctive lettering style — you’ve never switched to a computer font thankfully.

I never will.

Where did you learn your lettering? Was it just intuitive?

It’s functional lettering. It’s got to be legible. The first 2 books were lettered rather indifferently. Then I wised up and decided to learn how to do decent lettering. In a book of old fonts I discovered one called Elite — it’s easy to do, it looks sharp, kind of Deco-ish and a bit elegant. And, in a way, that elegance plays against Reid’s character.

Speaking of lettering: in comic book mythology Reid Fleming was conceived at the corner of Clint and Flicker Street. Can you tell us about this?

When I was first employed by Eclipse Comics I was given some guidelines: what to do, what not do. As far as lettering was concerned they advised me to be careful of inadvertent ligatures, due to possible blurring of ink in the printing process. They gave, as an example, two words to watch out for, being ‘clint’ and ‘flicker.’

And yet you built that into the last comic book that you did for Eclipse.

Yes, in the last chapter we see some historical movies during ‘The Milkman Banquet’, and there is a shot of company president Mr. O’Clock, revealing him to have been a milkman himself, long ago — this shot also exposes Mr. O’Clock as the real father of Reid Fleming. In the background we see that Mr. O’Clock is located at the intersection of two streets named Clint and Flicker. There is a certain lovely poetic symmetry to this.

Now for my last question. Do you, yourself, drink milk?

In my coffee.

So, you would see no need for a milkman? You would not pour a glass of warm milk before bed?

Oh, I’d never do that! Although, I’ll admit to the fact that I did drink an actual glass of milk just a couple of nights ago for the first time in eons to accompany some cookies made by my lovely niece Lila, who informed me that the cookies would taste better with milk. She was right!

World’s Toughest Cartoonist

appeared in CAROUSEL 29 (2012) — buy it here