From the Archive: ‘Improvisation is Important’ Jason Interview (CAROUSEL 30)

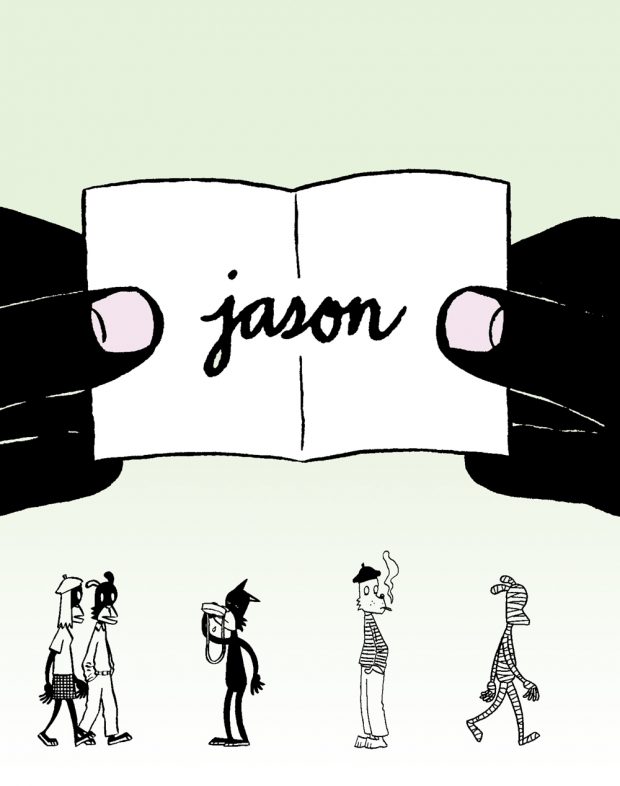

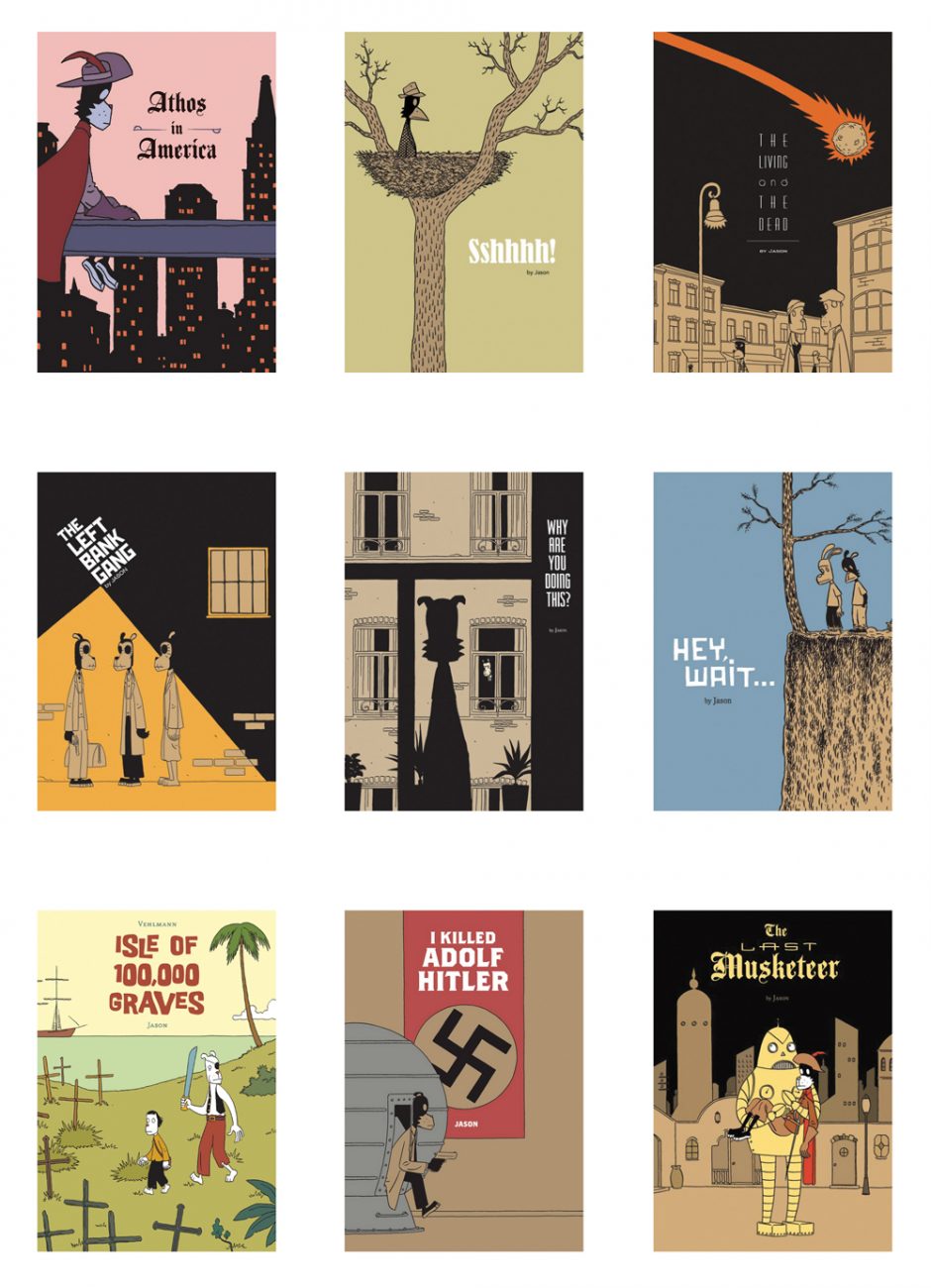

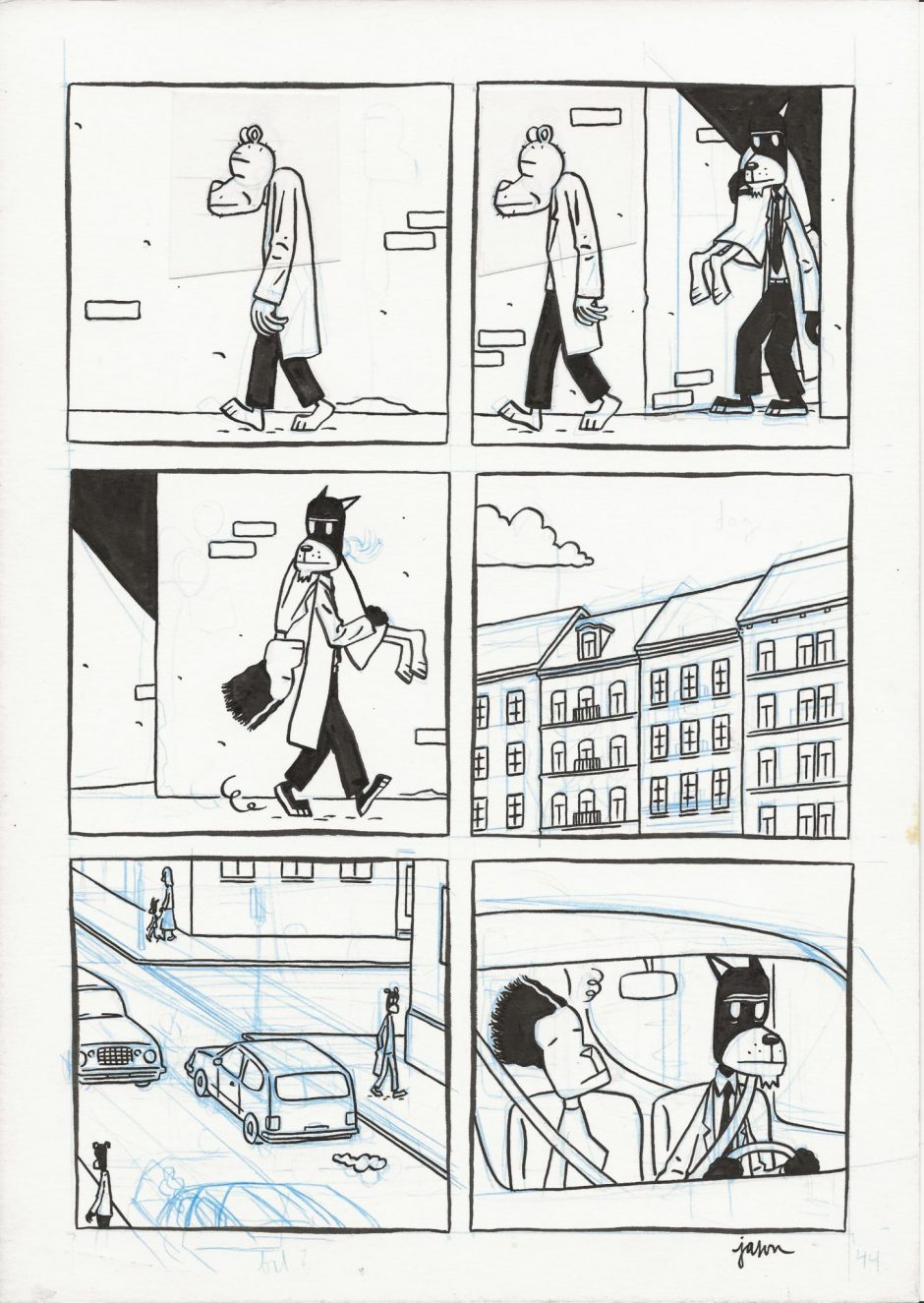

With a career spanning nearly two decades, Norwegian cartoonist Jason is undoubtedly one of world’s finest storytellers. Known for his sparse drawing style and anthropomorphic characters, he is the creator of a series of acclaimed, award-winning graphic novels that always deliver the perfect blend of humour and heartache.

Interview conducted May, 2012

Jason, can you give us an idea how you create a new work? I’m interested in how you break down the tasks, how you inhabit the different creative roles, where things overlap.

For me, drawing and writing are the same thing, I don’t separate those two tasks. I don’t write the script first and then do the drawings. I would be bored if I knew the whole story; it’s very much improvised. If I know three or four pages, I start working on those and then just think about what happens next in the story while I work on those pages. Sometimes the images come first and sometimes I have ideas for dialogue. There’s no single way of working; I try to keep it a bit open. Improvisation is important, it allows me to discover the story while I’m working.

And yet you are telling pretty distinct stories each time you take on a project. How do you manage to control a story arc within an improvisational structure?

I really wouldn’t know how to do it differently. As mentioned, it’s enough to find myself at the beginning, with a small idea, and to just start working. About one-third into the story, I know what direction the story will go, but still leave room for small detours. Usually around two-thirds into the story I have to start paying attention to how many pages I have left and how the story will end. It’s about noting the limits of the album size; it has to end on page forty-eight, it can’t go to page forty-nine.

You seem married to the short graphic album, the French standard size of forty-eight pages. You’ve done a lot with it.

I don’t really consider myself much of a writer, so for me the forty-eight page album has been sufficient until now. Sometimes, though, with the later works, when I’ve gotten the album back from the printer, often I’ve thought it could have been longer.

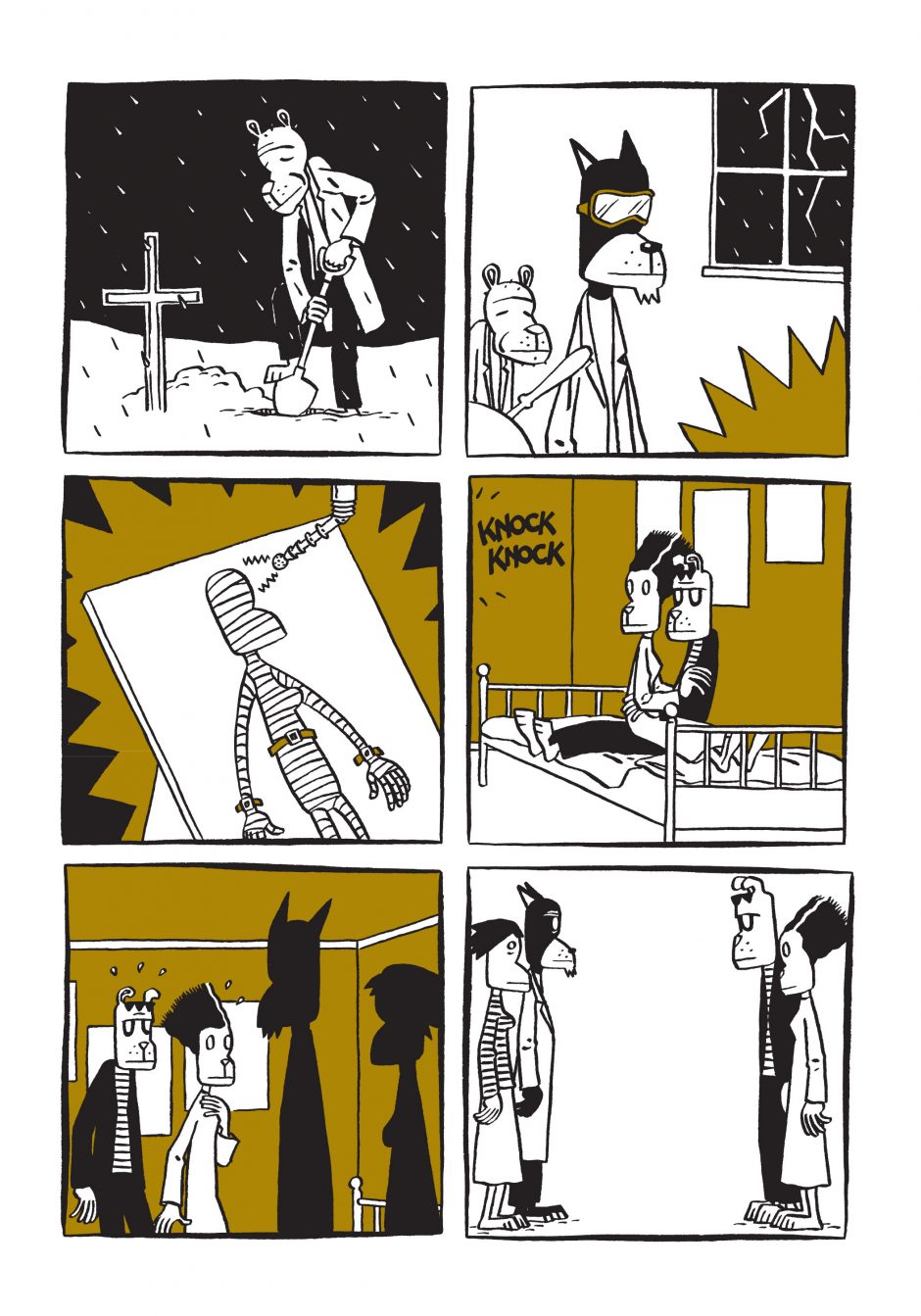

That’s the direction I want to go in, to do longer stories. The one I’m working on now is the longest story I’ve done so far, it should be around one-hundred-and-fifty pages — still keeping the improvisational approach, hopefully not getting lost along the way. To do seventy-five pages and then discover the story doesn’t work would be tough. So far I’ve been lucky; I’ve always reached the end in a way that I thought was satisfied. I wanted to work more on the writing and dialogue, fleshing out characters. I think that the writing is the more interesting part of doing comics, it’s not really the drawing.

I tend to agree; writing is the thing that can make a work masterful. It’s telling that you are putting the weight on the text, despite such a strong visual style.

I could never write a novel, I’m not really a writer in this way. I need to write in combination with images. I think it’s mostly the fact that I’ve been happy doing the shorter stories so far. It’s a challenge to try something longer, it’s the next step really. I used to do a lot of silent comics with no dialogue at all. Then, I started working with dialogue as a challenge. Now, I want to try something longer, to approach the form of a novel.

In comic book storytelling, the page can be a interesting measure. In traditional written fiction the page gives way to the narrative — it ideally disappears within the flow of the words. In comics, the page is a surface that’s meant to be noticed, it’s at the forefront of the experience. Talk about this in relation to your work.

I have both the page as a unit and also the spread in my mind when I work. I like to keep one page as one scene, it’s an important measure for the way I tell a story. That way I don’t have to work in chronological order; I can do scenes-as-pages and then figure out the right order at the end. One problem with comics is that it’s quite hard to edit; if you’ve drawn thirty pages and then find that a panel on page twenty-two doesn’t work, you can take it out, but then you have to put something else in instead. To work in scenes as I’ve described allows for an easier time in the edit; if you find a page doesn’t work, you can just take it out without having to put something else in. Or, if you feel something is missing between two pages, you can try to find something that might work to expand the story in that place.

When thinking about what will be the last panel on the right hand side of a spread, I always want to create some interest or curiousity in the reader, something that motivates them as they turn the page. With each page I try to strike a balance and a rhythm between the close-ups and full figures, visually it should look appealing to the eye. It’s something I strive for. You shouldn’t automatically think the reader wants to read your book. There should be something that makes him want to read it. For me, this goes back to Hergé’s Tintin, which I read as a kid. It was an inspiration then, and still is. There is very clear storytelling in Tintin. He often puts in some surprise element in the last panel to make you turn the page.

I feel that this kind of careful pacing has a lot in common with how poetry is constructed for the page. Do you see the connection between poetry and comics?

Yeah, I think so. Some of the later albums where each page has been one sequence, I think of them almost as poems.

There’s one page in The Left Bank Gang where the main character, Ernest Hemingway, is sitting in a café, writing. He notices a girl at the next table and he takes out a sketchbook and he draws her and then looks up and she has disappeared. She’s gone, he looks out the window and it’s raining outside. To me, it has sort of a unexplained, poetic quality; that’s what I tried to achieve in that sequence.

If I have some sort of rule in my comics, it’s to not give all the answers — to leave a little mystery, to leave something for the reader to interpret. I’m not really interested in reading books or watching movies where you just sit there and everything is given to you, and I try to reflect that in my own work. I think there should be some way in for readers to decide and make their own judgments about the story.

My story Hey Wait … , for example, has a very open ending. There have been some readers who ask me what happened at the end; I prefer not to say anything. Once there was a reader who was very insistent about wanting to know what happened at the end, so I gave him the answer — and he was disappointed. I think that if ten people read a book and have ten different impressions, it’s more interesting than if there’s only one.

Another thing that is open-ended is the way you choose to work with characters from book to book. You have created a number of distinct, visual personas that you utilize as ‘containers’, vessels to be recast in different roles, based on the narrative of each new work. Why did you decide to do that?

In the first book I did with a returning character, Why Are You Doing This?, I just liked the way the character looked, so I decided to keep him in the next one, which was the Hemingway book, The Left Bank Gang.

The main characters have the same look from book to book, but it’s a different person in every story. There’s also a secondary character who often appears, he’s also different each time. It’s a bit like the old John Ford movies, where he kept a recurring cast — John Wayne, Ward Bond and many other actors playing new characters each time. It creates some sort of unity between the books; the stories are different, but there’s something that ties them together at the same time.

For the reader, the blurriness of your anthropomorphic cast is compelling. Your approach flies in the face of our culture’s obsession with character design and the way characters tend to be named, branded and marketed as quickly as possible.

For me it’s not that important. I don’t do comics to sell dolls or greeting cards. The bird character, which might possibly be my most iconic character — even in a silhouette you can see who it is very easily — he doesn’t speak. It’s a silent character, so he has no name. I didn’t find it necessary to give him a name. For me, it’s the story that is the most important thing. There’s been an animation based on that character, created by somebody else. I gave the permission, but it’s not really something that interests me. I’m not trying to create an empire — I’m not Walt Disney.

Privately, do you have pet names for the characters you continually revisit or recast?

No. I don’t even know if it’s a dog or a cat. I have two or three archetypes, and then sometimes I change the ears or I change the nose a bit. He’s the main character, that’s how he looks. I don’t think it says anything about the personality. He can be a very typical hero in one story and then he can be a viscous killer in another, yet keep the same look. In one story he’s Ernest Hemingway, and then in the next he’s Athos the Musketeer. It’s not the same character from book to book, it’s purely visual, and therefore I prefer to give a new name in each story.

Your stories are entertaining, insightful, playful, yet they almost always reveal an existential exploration at their core; death clearly exists within your worlds. What is your position about this as an artist — are you working through your own ideas about mortality through your work?

It’s the Scandinavian in me, I think. There’s some darkness in my comics, but at the same time there’s a balance, I think; there’s some lightness also. I don’t really decide on anything before I start. I guess it’s who I am, people tell me they some sort of Scandinavian thing in my comics and it must be that darkness. If I’d grown up in Spain, would my comics be different? I don’t know. The stories are who you are. What can you do? Not to think about it too much, that’s the only solution.

Speaking of other places: there was a period where you were traveling a lot, living in several different countries. Was that impacting your work?

My style had pretty much arrived by that time. This was in my 30s; I’d finished art school and was trying to get a career going as an illustrator in Oslo. Since it’s a very expensive city to live in, and since there’s no comic book industry in Norway, I chose to go abroad when I decided I wanted to do more comics. I lived in Brussels, in Paris, and in Seattle and New York also for short periods — three months, which is the limit without a green card.

It’s not the traveling really that has an impact. It’s staying in one place for a longer time, which can give you ideas about stories. My first album-sized story in colour, Why Are You Doing This? — which is sort of a Hitchcock thriller — takes places in Brussels, where I was living at the time. The next one took place in Paris, and I made it while living there. The third one took place in Berlin, where I hadn’t been at the time. I went there for a week, taking photographs. I think the Berlin story is the one where I didn’t manage to capture the city in the story. I only had the photographs to look at, so it’s preferable to live for a longer time in one city.

How has settling down in Montpellier, France changed things?

I got a bit tired of moving around. I’ve been living in the south of France for the last six years, and a lot of the later stories have been set there in Montpellier. The first half of The Last Musketeer takes place in Montpellier, the second half takes place on Mars. Many of the recent short stories take place in Montpellier as well. The longer story I’m working on now is also set there.

It’s easier to reference what’s around me. When I have to draw an exterior scene, I can just look out the window or I can go out to a street and if I like it, I can just stand there drawing in the street.

What can you tell us about the new, long-form project you mentioned earlier?

It’s a detective story where the main character is a private eye, like in the movies from the ‘40s. He’s dressed like Humphrey Bogart in a trench coat and a fedora. The story takes place in Montpellier today, so you have this American icon walking around in a French city — I think it’s interesting to have this character out of time and out of place. Almost

automatically, I get story ideas from that set up.

Improvisation is Important: Interview with Jason

appeared in CAROUSEL 30 (2013) — buy it here